Some of the most remote, wild, and rugged landscapes of California’s central coast region are found in the backcountry of Santa Barbara, in an area known as the San Rafael Wilderness. These lands, nestled deep within the San Rafael Mountains, were set aside by Congress in 1968, and today they remain permanently protected under the Wilderness Act for current and future generations to explore and enjoy.

The area earned national fame as the first primitive area to be formally protected as Wilderness. In the 1960s, local residents worked with members of Congress and conservation groups in Washington DC to secure the strongest protections possible for this iconic landscape, laying the groundwork for future citizen-based wilderness initiatives throughout the country.

Early Years: The San Rafael Primitive Area

In 1929, the U.S. Forest Service began establishing a network of Primitive Areas throughout the national forest system. As part of that effort, Chief Forester Robert Y. Stuart established the 74,990-acre San Rafael Primitive Area in 1932, establishing the first-ever protections for the mountain range.

Yet the Primitive Area’s protected status was not absolute. Oil and gas leases were issued along the Sisquoc River, and the Forest Service proposed opening and paving the Buckhorn and Sierra Madre Ridge roads to accommodate an intensive development plan including a ski resort on Big Pine Mountain, major campgrounds, and vehicular use. The area was ultimately withdrawn from mineral leasing in the 1950s, and the development proposals met with strong opposition from local residents and never materialized.

San Rafael in the Spotlight

In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law. It required the Forest Service to review the suitability of all 34 existing Primitive Areas in the country for possible designation as Wilderness, and to report back to the President.

The San Rafael Primitive Area was the first primitive area to be reviewed under the Wilderness Act for possible designation as Wilderness. The area was capturing widespread attention, and two new books — California Condor: Vanishing American by Dick Smith and Bob Easton, and Rock Paintings of the Chumash by Campbell Grant — highlighted the need to further protect the area. The California condor was continuing its decline towards extinction, and the area was becoming known as one of the richest assemblages of Native American pictographs in North America. To many local residents, the fate of this area was clear — it must receive the strongest protection possible.

Wilderness: Dueling Proposals

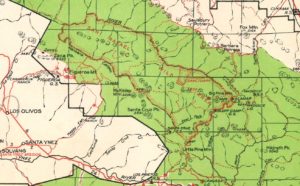

In 1965, the Forest Service completed its review of the San Rafael Primitive Area and recommended expanding the protected area into a 110,403-acre area dubbed the San Rafael Wilderness. Forest officials announced a public hearing and launched a formal comment and review period, heralding the first citizen-driven wilderness campaign in the country.

The beginning of the Lower Manzana Creek Trail in the San Rafael Wilderness — an area only partially included in the Forest Service’s original proposal. Local citizens later convinced the Forest Service to expand the wilderness to include most of the Manzana Creek watershed in their final proposal.

Local residents — advocating for a much larger protected area — argued that the Forest Service’s proposal omitted several key areas, leaving them vulnerable to development. They formed an ad-hoc committee called Citizens Committee for the San Rafael Wilderness led by Bob Easton, Fred Eissler, Dick Smith, Ken Millar, and Jim Mills. They promoted a much larger Wilderness proposal covering nearly 150,000 acres, protecting additional areas like Manzana Canyon, Big Pine Mountain and Madulce Peak, the southern flank of the Sierra Madre Ridge, and perhaps most importantly, the grassy potreros high atop the Sierra Madres known for their unique rock outcrops and Chumash rock art. These potreros were dubbed “Area F” and became the center of dispute between the citizens’ group and the Forest Service.

Bob Easton, a local author, journalist, and faculty member at Santa Barbara City College, became chair of the citizens’ committee and met frequently with Congressman Charles Teague, the area’s representative in Washington DC. Easton’s group enlisted the support of the City Council, along with the County Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors, and the group’s leaders mobilized the community to speak out in support of the larger citizens’ wilderness proposal.

A “History-Making Meeting”

More than two hundred people attended the Forest Service’s public hearing, in what civic leader Pearl Chase referred to as “a history-making meeting.” The overwhelming consensus of 57 speakers was that the area should be protected, with a great majority supporting the larger citizen proposal. The Forest Service received more than six hundred letters during the thirty-day public comment period following the hearing. The Santa Barbara News-Press, the New York Times, and the Washington Post all supported the citizens’ wilderness proposal.

But the citizens’ proposal also had its detractors. Santa Barbara County Supervisor Curtis Tunnell vehemently opposed any wilderness designation, arguing that native chaparral consumed too much water and wilderness designation would prevent the removal of chaparral in the Sisquoc River watershed. The American Forestry Association and the Izaak Walton League also opposed the establishment of the San Rafael Wilderness.

Rep. Charles M. Teague (left) and Senator Thomas Kuchel (right) — both California Republicans — introduced the legislation that established the San Rafael Wilderness.

As public support over wilderness preservation grew, the Forest Service expanded its wilderness recommendation to nearly 143,000 acres — a 30,000-acre increase over its initial proposal. In February 1967, Congressman Teague introduced the San Rafael Wilderness legislation in the House, and Senator Thomas Kuchel introduced companion legislation in the Senate. The Senate bill adopted the Forest Service’s recommendation, while the House bill included the additional 2,000 acres of potreros in Area F. The Forest Service strenuously opposed the inclusion of Area F, and was successful in stripping the 2,000 acres from the final bill. Following suit, the House and Senate agreed on a final bill that omitted the disputed potreros.

President Johnson Signs Wilderness Bill

On March 21, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the bill into law, formally establishing the San Rafael Wilderness. During the signing ceremony at the White House, the President noted:

“I want so much to protect and extend the legacy of our land. I want so much to take the pieces of our birthright that we should never have lost— and reclaim them, restore them and return them to the American people. San Rafael is part of that work…. Wilderness parks should be a part of the America of tomorrow — the kind of America that we think we are building today. I am very proud to sign this bill. I believe that it will enrich the spirit of America.”

The Expansion of the San Rafael Wilderness

Since 1968, the San Rafael Wilderness has been expanded two times. A small 2,000-acre chunk was added in 1984, expanding the area’s northwestern boundary to include the West Fork Mill Creek watershed and other unnamed tributaries to Manzana Creek.

In 1992, the Los Padres Condor Range and River Protection Act expanded the San Rafael Wilderness Area northward to include 46,400 of the La Brea Creek watershed located in the remote backcountry east of Santa Maria. The San Rafael Wilderness boundary has remained unchanged since then.

Rep. Salud Carbajal (CA-24) announces the introduction of the of the Central Coast Heritage Protection Act — which would substantially increase the size of the San Rafael Wilderness — in 2017.

In 2010, ForestWatch — along with The Wilderness Society and the California Wilderness Coalition — began working with local Congressional representatives on the third expansion of the San Rafael Wilderness. Most recently, Congressman Salud Carbajal and Senator Kamala Harris introduced the Central Coast Wild Heritage Act. That bill seeks to add approximately 66,000 acres to the San Rafael Wilderness as part of an overall effort to designate 250,000 acres of the forest as wilderness.

San Rafael Wilderness: The Next Fifty Years and Beyond

Today, the San Rafael Wilderness is one of the crown jewels of the central coast, spanning more than 191,000 acres of some of our region’s most remote and wild landscapes. While the area continues to retain its untrammeled wilderness character, it is also facing increasing challenges. Local residents, nonprofit organizations, and the U.S. Forest Service will continue working together to ensure that the wildness of the San Rafael endures for another fifty years and beyond.

- Invasive species are replacing native habitats and reducing the biodiversity of the San Rafael Wilderness. Tamarisk has invaded a significant portion of the Sisquoc River. In 2008, teams of ForestWatch volunteers conducted the first-ever comprehensive survey of tamarisk in the area, providing valuable data for ongoing eradication efforts. Yellow star-thistle is another invasive weed of concern.

- Endangered species seek refuge in the San Rafael Wilderness, with some glimmers of hope for their continued survival in the wild. California condors have returned to the San Rafael Wilderness after nearly fifty years of absence, and a condor nest was detected deep within the wilderness area in 2017. Efforts are also underway to restore endangered steelhead to their native streams, including removal of migration barriers like old dams and road crossings and modification of water releases from Twitchell Dam to ensure that fish have enough water during storms to make their way upstream to historic spawning grounds.

- Wildfire frequency is an increasing concern in the San Rafael Wilderness. Over the past fifty years, three wildfires have together burned nearly the entire wilderness area, beginning with the 1966 Wellman Fire, the 1993 Marre Fire, the 2007 Zaca Fire, and the 2009 La Brea Fire. Overly-frequent fire in chaparral can permanently alter the ecosystem, depleting the seed bank and making it prone to invasions of non-native weeds. There are still some small pockets of the San Rafael Wilderness that remain unburned in modern (post-1900) history, mainly centered along the middle segment of Manzana Creek and adjacent hillsides, but these areas of old-growth chaparral constitute less than 5% of the San Rafael Wilderness. Wildfire and drought will continue to shape this landscape as we face a changing climate.

- Scientific research is making a comeback in the San Rafael Wilderness, with several surveys and habitat restoration projects underway focusing on tamarisk eradication, data collection for big-cone Douglas firs and other rare plants, and archaeological findings. These actions are critical to further our understanding of how relatively untouched wild lands continue to evolve in a relatively natural state.

-

Outdoor recreation is one of the mainstays of the San Rafael Wilderness, with backcountry visitors traversing the area’s 125 miles of trails by foot or horseback. Faced with gradual reductions of Congressional funding over time, the Forest Service is no longer able to properly maintain all trails. In addition, traditional access points into the wilderness are restricted by neighboring landowners, with some trailheads — like the traverse from the Cuyama Valley to the wilderness boundary at Sierra Madre Road via Perkins Road — permanently blocked with gates and no trespassing signs.

- Resource extraction and development are encroaching closer to the wilderness area. A 2005 plan to expand oil drilling throughout the Los Padres National Forest would allow new oil wells to be developed within a half-mile of the wilderness boundary in Bates Canyon and Aliso Canyon. A lawsuit filed by ForestWatch in 2008 has put this plan on hold indefinitely. In addition, the largest commercial livestock operation in the Los Padres National Forest currently covers nearly 20,000 acres of the wilderness area.

Given the area’s rich natural and cultural heritage, iconic landscapes, wildlife habitat, and free-flowing rivers, the San Rafael Wilderness will endure for generations to come. And just as they have over the last half-century, local residents and conservation advocates will continue to play an important role in determining the fate of this majestic wilderness. Let us all take a moment to celebrate this land and the people who have worked tirelessly to protect and defend our region’s wilderness legacy.

Comments are closed.