Piru, Calif. – Ending nearly a decade of delay, the U.S. Forest Service has launched a long-term planning process for a portion of Piru Creek that straddles the boundary between the Los Padres and Angeles national forests in Ventura and Los Angeles counties. When completed, the plan will guide the future of the creek recognized under federal law for its scenic, geological, cultural, recreational, and biological features.

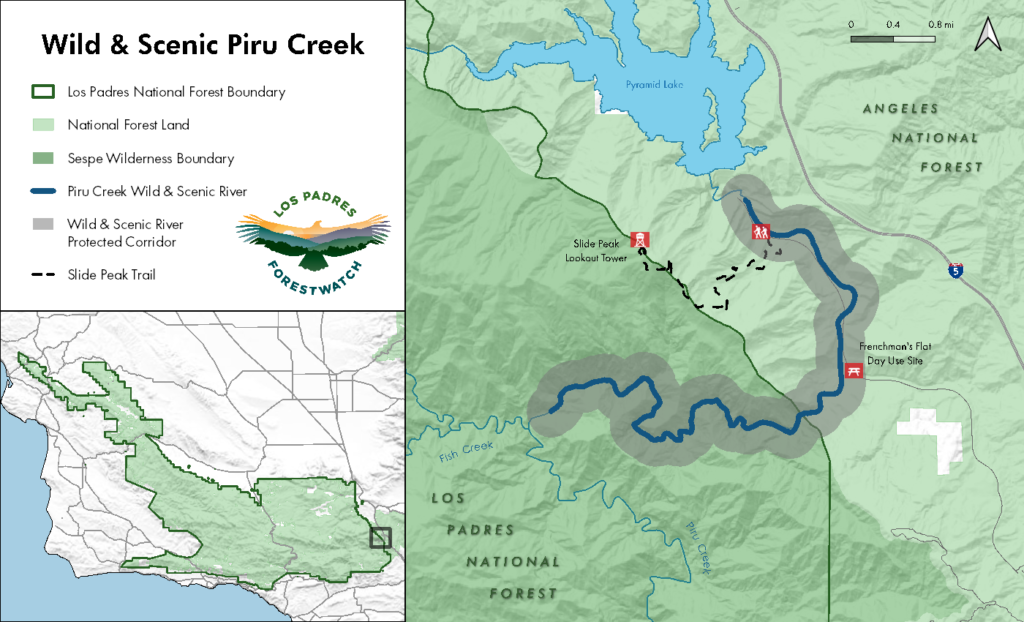

The plan—called a Comprehensive River Management Plan—covers a seven-mile stretch of Piru Creek from Pyramid Reservoir downstream through the Sespe Wilderness to the Ventura-Los Angeles county line. The creek segment is known for popular recreation areas like Frenchman’s Flat, where families from urban and nearby communities can experience nature and enjoy picnics and waterplay. The creek provides opportunities for catch-and-release trout fishing, swimming, rugged hiking and canyoneering, and whitewater rafting. Endangered California condors soar overhead, and the river and surrounding landscape are culturally important to local tribes and indigenous groups.

Piru Creek: A Local Treasure

Piru Creek is one of the largest river systems in the region, flowing for more than seventy miles through rugged and remote terrain, in some areas carving gorges more than one thousand feet deep. It originates from a series of small springs on the north face of Pine Mountain, flowing through the Sespe Wilderness before eventually emptying into the Santa Clara River. It is one of the largest river systems in the region and provides important wildlife habitat, water supplies for farms and homes, and exciting outdoor recreation opportunities including fishing, hiking, and whitewater rafting.

The lands around Piru Creek were originally inhabited by the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, in an area traditionally occupied by Ventureño Chumash. The name Piru is derived from the native word for the reeds used to make baskets.

Wild & Scenic River Designation

The need for a long-term management plan first arose in 2009 following passage of the Omnibus Public Lands Management Act. The legislation formally added millions of acres of public land in nine states to the National Wilderness Preservation System. It also designated thousands of miles of new additions to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. One of those segments was Piru Creek.

The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System was established by Congress in 1968 to serve as our nation’s strongest form of protection for free-flowing rivers and streams and now consists of more than 13,000 miles of waterways across the U.S. Once a river is added to the system, it triggers a three-year requirement to prepare a “comprehensive management plan” for the river. The plan must be developed with input from the public and must describe the river’s “outstandingly remarkable values” – those things that make the river unique and worthy of protection, and that should be safeguarded in perpetuity.

Properly identifying the values of a “wild and scenic” river is important because it lays the foundation for the management plan and guides future actions and decisions affecting the waterway and a ¼ mile buffer zone along both sides. Future decisions must be consistent with the river corridor management plan and cannot harm the values identified for protection.

A History of Delay and Inaction

The Forest Service started evaluating Piru Creek’s eligibility for “wild and scenic” designation in the 1980s, but concluded in 1988 that it was not suitable for special protection. Several conservation groups formally challenged that determination by filing an appeal, prompting the Forest Service to revisit the matter.

The agency eventually found that this segment was suitable for “wild and scenic” protection but omitted this determination in a draft management plan for the forest in 2004, once again denying protections for Piru Creek. Conservation groups have criticized the Forest Service’s chronic reluctance and considerable internal ambivalence to recognize all the ways this creek segment is worthy of protection.

Congress ultimately stepped in, formally designating this seven-mile segment of Piru Creek as “wild and scenic” and triggering a three-year time frame for completing a management plan for the creek. Yet those three years came and went without any action. As a result, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit in 2018, seeking a court order to compel the agency to begin the planning process.

It wasn’t the first time Los Padres National Forest officials landed in court for failing to prepare a mandated management plan for a “wild and scenic” river. In 1992, Congress protected three other waterways—Sespe, Sisquoc, and Big Sur—but took eleven years to complete those plans and only after those delays were challenged in court.

A similar pattern emerged with the most recent seven-mile Piru Creek segment, and following the Center’s 2018 lawsuit, the Forest Service agreed to complete the Piru Creek management plan by the end of 2024.

First Step: A Values Assessment

The initial step in creating a management plan for Piru Creek is to identify the things that make the waterway unique and worthy of protection. Once we know what values we are protecting, we can then determine the best ways to protect them.

On its way toward meeting the 2024 deadline, the U.S. Forest Service released its River Values Assessment for Piru Creek in July 2022. The 24-page assessment concluded that Piru Creek contained outstandingly remarkable values for geology and fishing, but—much to the dismay of river and fishery conservation groups—not for scenery, recreation, plants and wildlife, or cultural resources.

As a result, this summer several groups—ForestWatch, Center for Biological Diversity, CalWild, American Whitewater, Sierra Club, Fisheries Resource Volunteer Corps, and Community Hiking Club—joined together to urge the Forest Service to recognize all values of Piru Creek. The Forest Service is expected to complete its values assessment and release a management plan and environmental study in the coming months.

New Threats, New Opportunities

In the meantime, Congress is considering extending “wild and scenic” protection to the remainder of Piru Creek upstream of this seven-mile segment. That legislation—the Central Coast Heritage Protection Act—has passed the House and is awaiting action in the Senate. The bill, and the protection it would bring, became more urgent after the Forest Service this summer proposed to remove trees and clear vegetation along a 20-mile stretch of Piru Creek, extending thousands of feet away from the river banks in some places.

Piru Creek remains one of the crown jewels of our region, but its fate remains uncertain. ForestWatch and our allies will continue to demand a thorough and complete values assessment for Piru Creek, a strong management plan, a stop to logging and vegetation clearing, and the extension of “wild and scenic” designation for the upper watershed. The future of Piru Creek depends on it.

Comments are closed.