Pinus coulteri

- Near Threatened – IUCN Red List

Coulter pine is an evergreen conifer native to the coastal mountains from central California to the Baja peninsula and is well-established within the Los Padres National Forest. The species was named after Irish botanist, Thomas Coulter, who described many California native species and sometimes collaborated with David Douglas of Douglas fir fame.

Description

Depending on site conditions, these pines can grow to a height of between 30 to 85 feet tall and can have a diameter of over 2.5 feet. Needles occur in bundles of three and are 6 to 12 inches long. Coulter pines can reach over 100 years of age.

Coulter pines are most easily identifiable by their massive spiny cones, which can be as long as 20 inches and are the heaviest and largest of any true pine (Pinus spp.), weighing up to 8 pounds. In fact, when the Coulter pine first bears cones at an age of 10-15 years, the cones stem from the trunk of the tree because the branches are not yet strong enough to bear the weight of the cones until the tree is fully mature.

Each cone carries around 150 seeds which are protected by thick, talon-like claws. These cones are often mixed up with those of another chaparral neighbor, the gray pine (Pinus sabiniana)—the cones of which tend to be wider and shorter. It might be best to avoid pitching a tent under either of these species.

Habitat

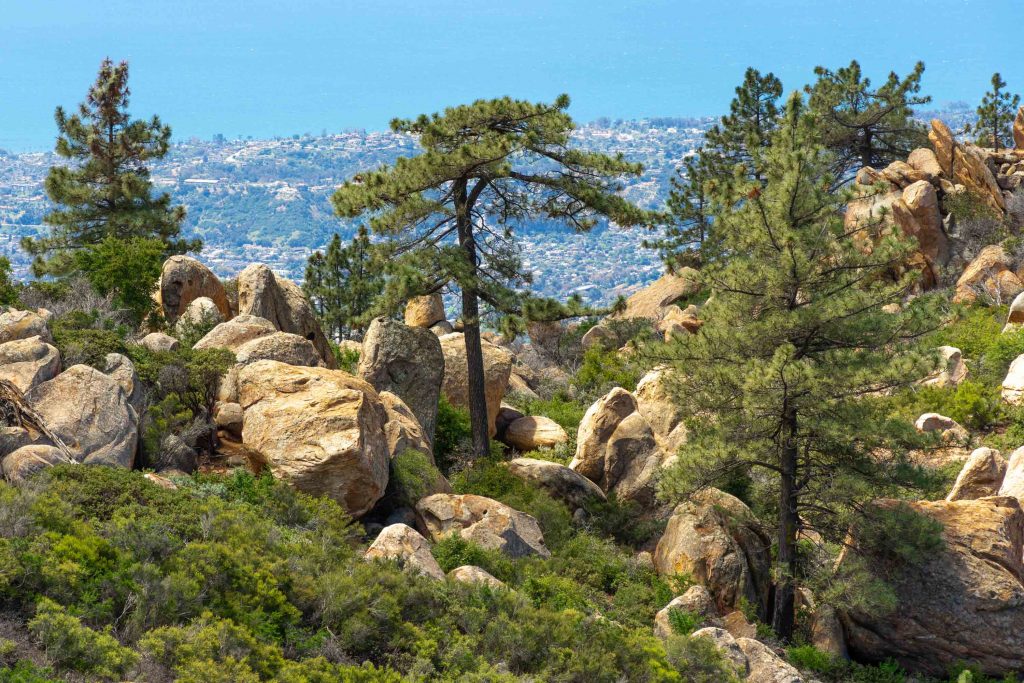

Stands of Coulter pines are most commonly found in and around chaparral-dominated areas on south-facing slopes and ridges anywhere from 2,000 to 7,200 feet in elevation. These pines can grow in a wide variety of soils ranging from poor to fertile and loamy to rocky, though sites are typically dry. Subsequently, mature Coulter pines are drought-tolerant, yet can survive in shade. Conversely, saplings can grow in partial shade yet require soil moisture.

Ecology

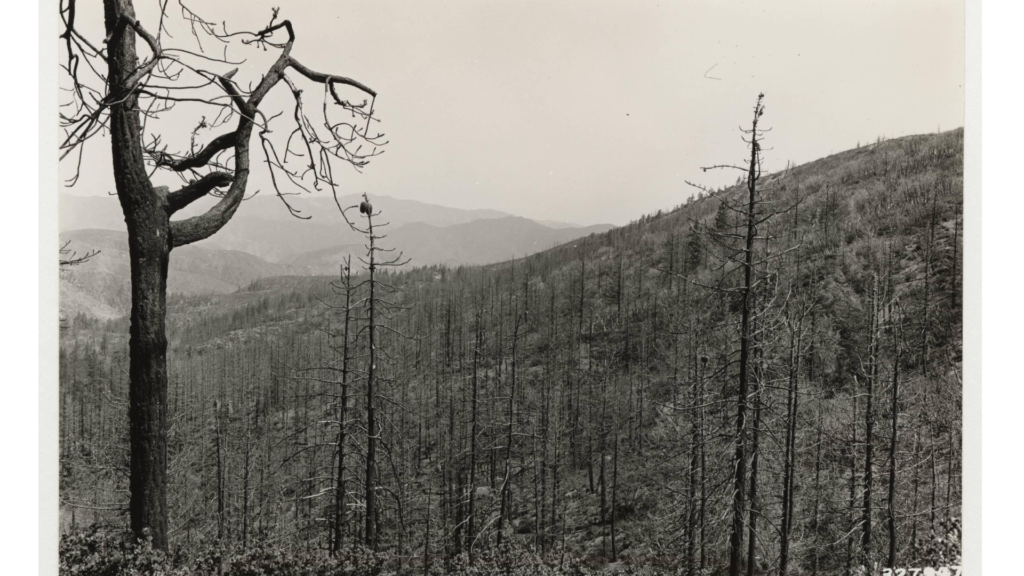

Depending on where they’re found, the cones of Coulter pines will sometimes only open from the heat of high-intensity fire (this trait is known as serotiny). However, the degree of serotiny among Coulter pines can be variable. In our region, Coulter pines are adapted to infrequent high-intensity fire that generally occurs in the adjacent chaparral ecosystem and typically dense understory. This fire adaptation is not the same as thick-barked conifers such as Jeffrey pine or bigcone Douglas-fir or resprouting trees like California bay laurel. Rather, it’s their ability to regenerate from seed after infrequent stand-replacing fire that allows populations to persist under such a fire regime. There is historical evidence of high-severity fires killing entire stands of this species in places like Big Pine Mountain, where the Coulter pines typically come back within a few decades.

Distribution in the Los Padres

In the Los Padres National Forest, Coulter pines can be found sporadically along the Santa Ynez Mountains crest and in denser stands at higher elevations such as around Figueroa Mountain, Big Pine Mountain, in the mountains near San Luis Obispo, and throughout the Big Sur area.

Conservation

While Coulter pines have a limited distribution compared to other pine species, they are not considered threatened or endangered. The primary threat they face in the Los Padres National Forest is from vegetation clearance projects targeting naturally dense forests on mountains outside of designated wilderness areas.

Coulter pine is one of twelve management indicator species (“MIS”) the Forest Service uses to evaluate the effects of land use activities on the Los Padres National Forest. The Forest Service monitors Coulter pine stands to examine changes in fire frequency.