On the evening of April 22, 1922, a group 200 or so men donned masks and raided the Elduayen family home in Inglewood, CA. The raiders seized Spanish immigrants Fidel Elduayen and his brother Mathias, threatening them with death on suspicion of the men being bootleggers. One of the raiders, a constable in the town, was shot and killed by police during the incident. It was quickly discovered that the raiding party was largely comprised of members of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). At a time when the Klan was at its most popular while also causing mayhem across the country, the raid made headlines and resulted in a massive investigation into the organization’s dealings in California.

So what does this have to do with a mountain in the Los Padres National Forest?

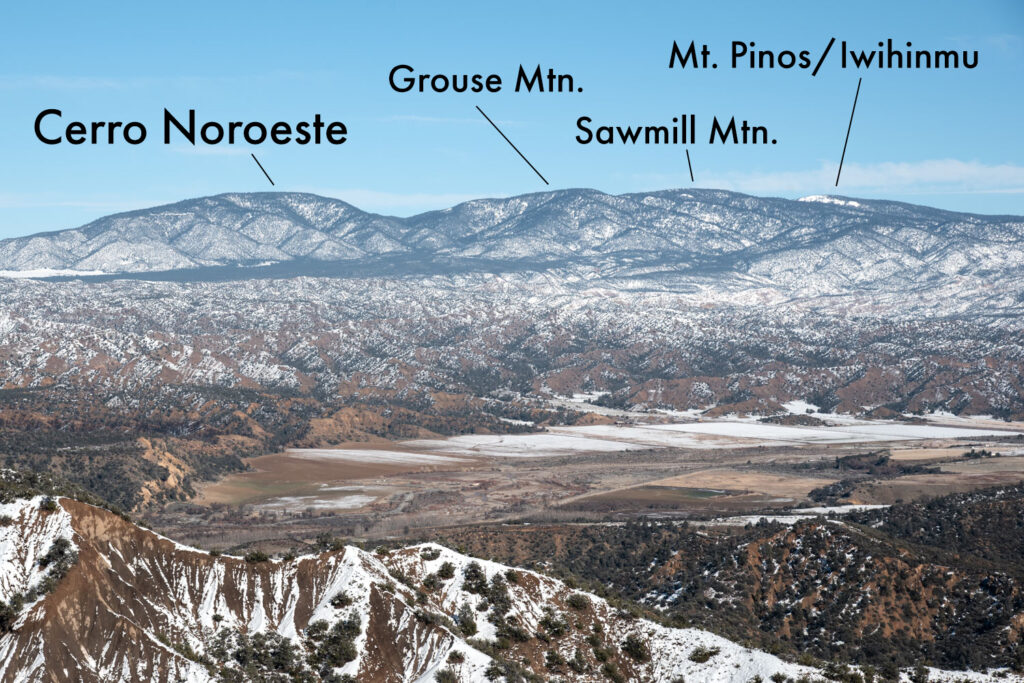

Cerro Noroeste (“Northwest Mountain” in Spanish) rises to 8,283 ft, one of just five peaks in the Los Padres National Forest that breaks 8,000 ft. The mountain is located about three miles west of Mt. Pinos/Iwihinmu, just north of the Ventura-Kern County line. It is the western terminus of the beloved Vincent Tumamait Trail that connects the highest peaks in the national forest.

During the 1930s, newspapers in the area started referring to Cerro Noroeste as Mt. Abel in honor of Stanley Abel, a Taft-based oil driller who was elected as Kern County’s 4th District Supervisor in 1917. Abel was seen as instrumental in getting a road built to the top of the mountain in the mid ’30s. However, the mountain was never officially named Mt. Abel. The Forest Service even announced in 1941 that the legal title had been and would continue to be Cerro Noroeste. Of course, this wasn’t the Indigenous name for the mountain, but to anyone who was paying attention to the news in the ’20s, it was a vast improvement over Mt. Abel.

The investigation into the Inglewood raid of April 1922 led authorities to search the offices of a Los Angeles-based attorney who also served as the “Supreme Attorney” and “Grand Goblin” of the KKK’s California enterprises. A trove of documents was found, including lists of thousands of official KKK members across California. The lists included hundreds of policemen, elected officials, staffers in district attorneys’ offices, and other people with respected positions in the community.

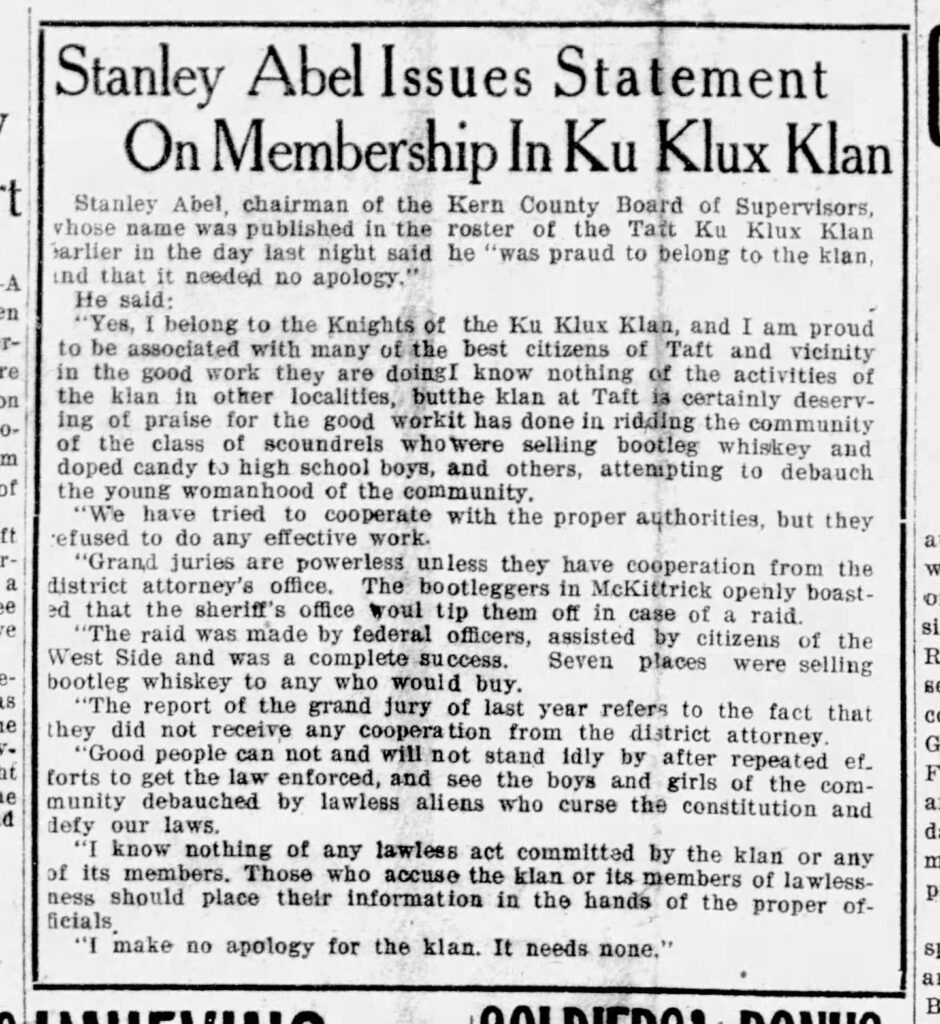

Stanley Abel, five years into his time as a Kern County supervisor, was named on one of those lists. He was an active member of the Klan in Taft.

On May 6 of that year, the Bakersfield Californian published a front page story about the staggering number of elected officials in Kern County who were part of the KKK. In addition to Abel, others on the Klan’s rolls included the Bakersfield Chief of Police and several local city council members. The secret but expansive network in Kern County had been revealed, and it seemed to infect just about every part of society with its white nationalism.

When confronted with this revelation, Stanley Abel was unapologetic to say the least. He said in a statement the day after the Bakersfield Californian published their report:

“Yes, I belong to the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and I am proud to be associated with many of the best citizens of Taft and vicinity in the good work they are doing….I make no apology for the Klan. It needs none.”

Many people in Kern County were not impressed. They started recall campaigns for Abel and others in city and county governments. Local newspaper the Bakersfield Morning Echo was in staunch support of the supervisor, stating:

“Promoting the recall of Stanley Abel are the enemies of good society and of the best interests of Kern County….A vote for the recall of Stanley Abel is a vote for the return of the vicious element and the vicious conditions which existed in years gone by.”

Abel defeated a recall by just 103 votes (less than 3% of all votes cast) a few months later, and he would continue serving as a county supervisor until 1940. To our knowledge, he never renounced his membership in the KKK. Yet, to this day people in the general area still sometimes refer to Cerro Noroeste as Mt. Abel. Newspapers in Kern County mostly referred to the mountain by its correct name during the ’40s and ’50s. But the Bakersfield Californian again used the name Mt. Abel inconsistently in the ’60s and ’70s. The USGS Board on Geographic Names had to reaffirm the mountain’s official name as Cerro Noroeste in 1988.

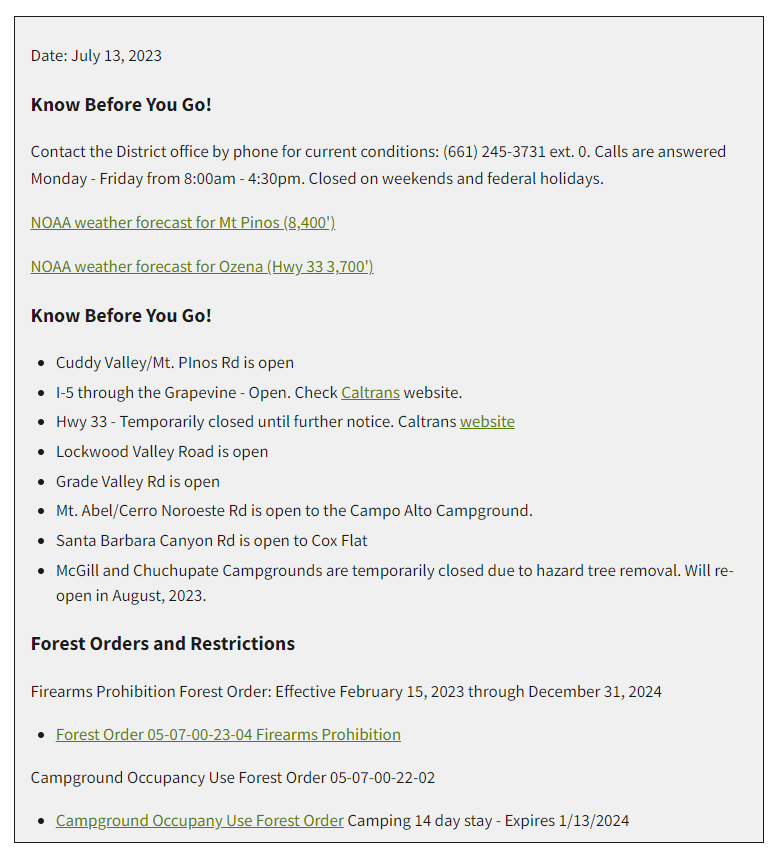

Strangely, the Forest Service’s own website still has references to Mt. Abel. The agency’s webpage about road conditions in the Mt. Pinos Ranger District says “Mt. Abel/Cerro Noroeste” in multiple locations. Even the recreation.gov page for Campo Alto, the campground atop the mountain, mentions the name. It should be noted that there are other places with the name Abel, such as a campground along the Sisquoc River, but these appear to be named after a different man according to Jim Blakely’s 1985 Historical Overview of the Los Padres National Forest.

The Inglewood raid in 1922 eventually led to the State of California outlawing the KKK. The organization’s popularity across the country fell dramatically by the end of the ’20s, and it wouldn’t see another resurgence until the ’60s when the Civil Rights Movement was in full swing. Knowing, understanding, and talking about the past is vital to our ability to progress as a society, but we see no reason why anyone should continue to use the name Mt. Abel. Knowing this past, and often present, unofficial name of Cerro Noroeste may give people the sense that they’re using a secret, locals-only name for a beloved mountain. In reality, use of the name intentionally or unintentionally glorifies a man who long remained proud to be part of one of the most hate-filled, violent, and reviled organizations to ever exist in the United States.

Comments are closed.