Spea hammondii

- Under Review – Endangered Species Act (2015)

- Near Threatened – IUCN Red List (2016)

- G3 Vulnerable – NatureServe

- Species of Special Concern – California Department of Fish and Wildlife

- Sensitive – Bureau of Land Management

Habitat and Range

Habitat and Range

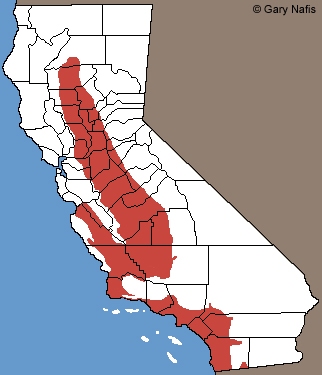

The habitat of the western spadefoot ranges from northern Baja California in Mexico to central California. In California, the western spadefoot is found in the Coastal Ranges south of Monterey County, the Central Valley and the Central Valley’s adjacent foothills. Spadefoots are found in the following counties in the Los Padres National Forest: Kern County, Santa Barbara County, San Luis Obispo County and Monterey County. It’s range also includes the Carrizo Plain National Monument.

They primarily live in grassland habitats, but some have been observed to live in pine oak woodlands in the foothills. Outside of the breeding season, they live in burrows (usually made by other mammals) that are about 3 feet deep and migrate to seasonal vernal pools to reproduce. They are also opportunistic and will use small puddles of waters, such as small pools near roads, to breed. The biggest difference in the spadefoot’s current distribution from their historical range is that spadefoots have been eliminated in urban and agriculturally developed areas.

The western spadefoot toad’s range includes portions of the Los Padres National Forest, especially in San Luis Obispo County. It also ranges across the Carrizo Plain National Monument.

Life Cycle

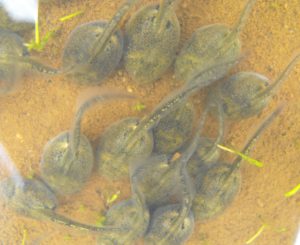

The average lifespan for a western spadefoot toad is about 12 years. In the late winter and early spring, adult spadefoots will seek vernal pools to use for their breeding grounds a few days after the winter rains filled them with water. Males can be heard at this time. A single female spadefoot will lay hundreds of eggs in a season in clusters (called a “spawn”) that contain about 10 to 40 eggs. The spawn is covered in a clear jelly and laid in a long chain (called a “cordon”) that attaches to objects in the water, such as plant material. The male will then fertilize the egg in a process called amplexus, where the male jumps on the female’s back and deposits sperm on the cordon.

Western spadefoot toads mating. Photo by Bernard Dupont.

Tadpoles will hatch between three to four days, or even as little as 15 hours after fertilization. It takes about 8 weeks for tadpoles to undergo metamorphosis into young toads, which is the fastest metamorphosis known for any frog or toad species, and about 2 years before they grow into fully mature toads. But tadpoles risk mortality if the vernal pools dry up before they successfully grow past the first larval period of about 30 days. Unfortunately, there is usually high mortality rates due to desiccation during the breeding season, as it is common for the toads to lay eggs in pools that stay filled for only 3 to 4 weeks.

At 9 to 12 weeks, the tadpole will begin to develop its lungs, grow its front legs and have its tail shortened until it develops into a young toad at about 12 weeks. The young toad may remain in the vernal pool for another 1 to 3 weeks before leaving the water in search of more food. It will return to the vernal pools in 1 to 2 years to breed.

At 9 to 12 weeks, the tadpole will begin to develop its lungs, grow its front legs and have its tail shortened until it develops into a young toad at about 12 weeks. The young toad may remain in the vernal pool for another 1 to 3 weeks before leaving the water in search of more food. It will return to the vernal pools in 1 to 2 years to breed.

Threats

The biggest threats to the western spadefoot toad is the loss of its habitat, especially for breeding. Urban and agricultural development has greatly diminished their habitat by eliminating it completely or changing the hydroperiod of vernal pools so that they are incompatible with the spadefoot breeding season. Since the 1950s, there has been a substantial spadefoot population decline in California. A 30% population decline has been observed in northern California and the Central Valley, while an 80% population decline has been observed in southern California due to development. Additionally, it is estimated that most of vernal pools in California have been lost since the arrival of Spanish explorers (although the exact amount is unknown due to a lack of historical data). Climate change also threatens spadefoots as increased drought can lead to higher rates of mortality due to pools drying out sooner. Some spadefoots have been eliminated in parts of their range due to habitat loss.

Vernal pools such as this one in the Carrizo Plain National Monument are vitally important to the survival of the western spadefoot toad. Photo by Bill Bouton.

Conservation

The western spadefoot toads is listed as a Species of Special Concern in the state of California and is considered “sensitive” by the Bureau of Land Management. An official request for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect the species under the Endangered Species Act was recently submitted. The agency is still reviewing whether to list the species as threatened or endangered. Conservation efforts include preserving their habitat, especially the few remaining vernal pools in the state, and maintaining an equilibrium between development and their undeveloped habitat. Vernal pools are critical habitat for many rare and endemic species and in California they are protected by state and federal laws. The state’s recovery plan includes habitat protection, research, participation, outreach, status surveys for species of interest (including the western spadefoot), adaptive habitat management, restoration, and monitoring. The vernal pools do not attract many predators, which makes the restoration efforts of the spadefoot arguably simpler than other species, but special care is needed to make sure that their breeding grounds are absent of bullfrogs, introduced tiger salamanders, and introduced fish that prey on the spadefoot larvae.

ForestWatch works to protect vernal pools throughout the Los Padres National Forest. We have submitted technical comments on projects that would impact vernal pools to ensure that species such as the western spadefoot toad is protected.