Aquila chrysaetos

- Fully Protected – California Department of Fish and Wildlife

The golden eagle is one of the largest, fastest raptors in North America. Its brilliant golden feathers, cunning intelligence, powerful stance, and fierce tactics make it the most common official national animal in the world. It has claimed its place as the symbol of Germany, Austria, Mexico, Kazakhstan, and Albania.

Golden eagles can see 5 times farther than the average human, meaning they have 20/4 vision. Their eyes don’t move in their eye sockets but they can rotate their heads 270 degrees to look around. Each eagle has about 7,000 feathers, creating a breathable protective layer that also acts as a waterproof raincoat. The world’s oldest golden eagle was at least 31 years old but they can live to be 50 years old under human supervision.

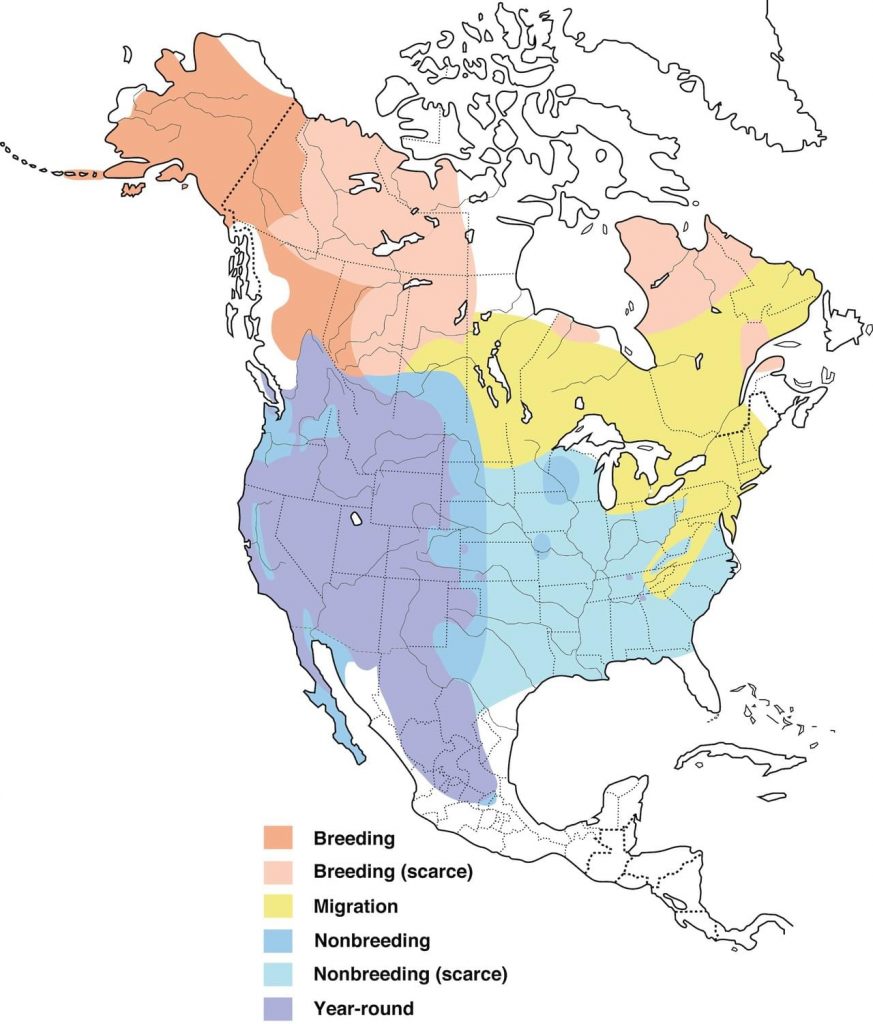

Distribution

Golden eagles are found throughout North America, but they are most common in the West. They live in a wide range of habitats including tundras, grasslands, canyons, forested habitats, woodlands, shrublands, and even arid deserts. Most golden eagles in California stay in the state year-round, moving downslope in the winter and upslope after breeding season. Upon first snowfall, the eagles that live in Alaska and Canada migrate thousands of miles south to the United States to wintering grounds.

Golden eagles are found throughout the Los Padres National Forest. They are known to occupy some areas such as the Sespe Wilderness, where you may mistake one flying overhead for a California condor.

Habitat

Golden eagles require open terrain, whether it be in open mountains, canyonlands, foothills, rimrock terrain, cliffs, bluffs, or plains. They avoid developed areas and are not keen on dense, uninterrupted stretches of forests. They have a very wide range during the winter and are more restricted to areas with good nest sites in the summer. Good nest sites include cliffs, steep escarpments in grasslands, chaparral, shrubland, and other vegetated areas.

Mating and Nesting

Golden eagles are monogamous and they often mate for life. During the initial courtship, the male will attempt to impress the female by folding his wings, dropping headfirst, and soaring up just before hitting the ground. He will repeat this dive up to 20 times, beating his wings at the top of each rise. If this aerial display of affection impresses her, the female will circle the male and join him in a dance of shallow dives. While golden eagles are usually silent, the two lovebirds will make shrill, high-pitched rhythms during mating and nesting season.

Golden eagle pairs build several nests in their territory as they grow old together. A territory can contain up to 14 nests. They prefer strong, bowl-shaped platforms in steep cliffs or large trees that can provide unobstructed views of the surrounding landscape. They build their nest with tree branches and reinforce it with other hard items they find such as bones, antlers, and human-made objects. They line the nest with vegetation such as grasses, leaves, mosses, lichens, and bark—often including aromatic leaves to keep insects away. These intricate nests grow to be 6 feet wide and 2 feet deep. The largest recorded golden eagle nest was 20 feet tall and 8.5 feet wide. These nest sites may be used by the couple for years to come, adding materials that make it bigger each year.

Golden eagle pairs prefer to maintain breeding territories of 2,800 to 4,900 acres. Much more aggressive than bald eagles, golden eagles will attack intruders by repeatedly diving at them and displaying skillful acrobatics as they soar through the air.

Female golden eagles lay 1-3 eggs, each about 3-5 days apart sometime in the period between January and May. The incubation period is about 41-45 days and the female stays with the nest while the male hunts and brings back prey.

After the eaglets have hatched, they must lay in the nest between 60-70 days before first flight. Golden eagles average 1 eaglet per year and can raise as many as 15 in their lifetime. The nesting season is long, extending more than 6 months from the time the eggs are laid until the eaglets reach independence. Youngsters often play dive with each other and make games out of sticks and stones.

Feeding

While closely related to the Bald Eagle, the golden eagle is more of a predator and less of a scavenger. The golden eagle has astounding speed, reaching 120 mph in pursuit of its prey. It can use a large variety of hunting techniques including high soaring, low flight, still-hunting, and running on the ground. Once the prey is spotted, the eagle plunges toward it and kills it with its sharp talons. Golden eagles feed primarily on animals such as rabbits, rodents, carrion, foxes, cranes, and mid-sized reptiles. They’ve been seen killing mountain goats, sheep, coyotes, badgers, bobcats and even seals. Mating pairs hunt together with one eagle distracting the animal while the other goes in for the kill. Golden eagles also love playing with their food. After catching and killing their prey, they’ll carry it high up into the air, drop it down, and dash to retrieve it.

Threats

Although Golden eagles have a wide distribution across many continents, their population is declining in areas where human populations are thriving. Human development has lead to loss of nesting habitat, loss of foraging area, and collision with man-made objects. Thankfully, because their cuisine consists primarily of mammals, these birds escaped the harm faced by fish-eating and bird-eating raptors from DDT and related chemicals.

Humans are the greatest threat to eagle populations. Urbanization, development, and more frequent wildfire cycles have destroyed nesting and foraging sites in southern California. Despite being federally protected by the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, thousands of golden eagles have been killed by ranchers that falsely believed eagles were preying on their young livestock. In reality, very few farm animals were killed because golden eagles prey mostly on small mammals. Some eagles have been poisoned by prey animals set out to control coyotes. Another threat to these creatures is lead poisoning. Golden eagles have been found with lead poisoning caused by lead bullet fragments in the meat of their prey. Thankfully, as of July 2019, hunting with lead bullets has been banned in California.

Most recorded deaths are from collisions with vehicles and man-made structures. Golden eagles face the threat of electrocution when their feet touch a power line and form a circuit. Since the 1970s, biologists, engineers, and government officials have cooperated to build “raptor-safe” powerlines to prevent this fate. One of the biggest threats is the growing incidence of death caused by wind turbines. Since 1998, nearly 2,000 golden eagles have been killed in the Altamont Wind Resource Area in California.

Conservation

Golden eagles are protected by three federal laws: The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and the Lacey Act. These laws help ensure the future success of eagle populations in the wild. The most recent survey of golden eagles in four large Bird Conservation Regions in the lower 48 states has found an estimate of roughly 20,000 eagles, indicating a stable population (Department of Fish and Wildlife Service). It’s difficult to confidently assess long-term population trends because golden eagle populations undergo a ten year cycle and the Department of Fish and Wildlife Service only has four years of data (2006-2009). Unfortunately, little is known about their population in California.

In 2009, the federal government granted the wind energy industry permission to kill eagles for up to five years in an effort to support the production of renewable energy. In 2013, the rule was changed to 30 year permits. In 2014, the American Bird Conservancy filed a lawsuit on this extension and declared victory in 2015.

Eagle populations are restored through the technique of “hacking.” Humans rear eaglets in the lab and feed them until they are 12 weeks old. At this time, the cage is opened and the younglings begin feeding themselves. They continue to receive handouts until they are old enough to be independent in the wild.