The howl of a coyote is emblematic of the American West, and despite relentless attempts to eradicate them—including here along California’s central coast—coyotes have persevered, survived, and adapted. They are featured prominently in Indigenous stories and culture, and play an important ecological role.

Coyotes are found from Costa Rica to northern Alaska, and from coast to coast, covering nearly every part of North and Central America. They are divided into 19 different subspecies and are known by nearly as many different names—brush wolf, prairie wolf, sage wolf, song dog, yote, yodel dogs, pasture poodles, and the legendary Wile E., among many others. To biologists, they are simply Canis latrans, genetically related to other wild canines like wolves and foxes.

Roaming our region are California valley coyotes (Canis latrans ochropus). This subspecies is found throughout California, west of the Sierra Nevada. Other types of coyotes are found in the San Diego area (San Pedro Martir coyote), northern California (Northwest coast coyote), eastern California (mountain coyote), and southeastern California (Mearns coyote). Each subspecies varies slightly by size and coloration, but they are difficult to tell apart.

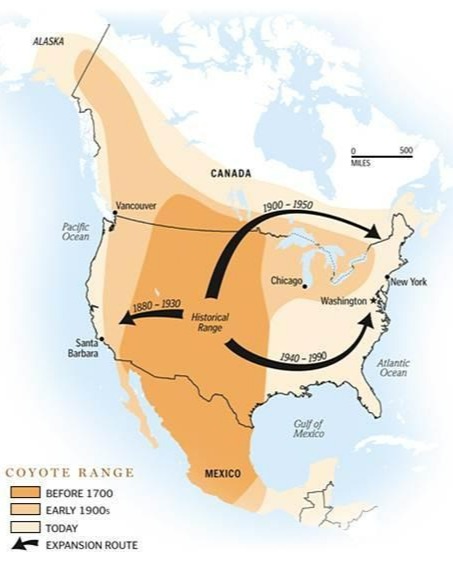

Coyotes weren’t always here, though. They were originally restricted to the prairies and deserts of Mexico and central North America. By the late 1800s, they had expanded westward to California, northward to Alaska, and continued their movement eastward into the 1900s, now found all over the U.S., Mexico, and southern Canada. This expansion came despite (and partly because of) widespread efforts to exterminate coyotes, and movement into areas where wolves had been eradicated from the landscape.

Nature’s Survivalists

Coyotes are one of the most adaptable animals, able to change their behavior to fit their surroundings and thriving in just about any type of habitat, from deep in the remote wilderness to urban parks. They can travel in packs or be solitary, breed prolifically or sparingly, and can eat just about anything—rodents, mammals large and small, frogs, reptiles, fish, berries, and even birds. They are expert hunters that keep rodent populations at bay, reaching speeds of up to 40 mph (about twice as fast as a roadrunner, by the way).

Often mistaken for dogs, coyotes can weigh 15 to 46 pounds. The California valley coyote is smaller, averaging around 30 pounds. They mate for life and parent together, raising litters with 5-7 pups in dens. The average lifespan of a coyote is around 10 years.

Coyotes are one of the most vocal animals in North America, Researchers have identified 11 different vocalizations: growl, huff, woof, bark, bark-howl, lone howl, group yip-howl, whine, group howl, greeting songs, and yelps. Each vocalization represents a different way of communicating with other coyotes.

California vs. The Coyote

Spoiler alert: coyote wins.

As coyotes became more prevalent in California, they faced widespread persecution. In the late 1800s, the state legislature authorized counties to offer bounties to kill coyotes and other wildlife. San Luis Obispo County offered its first bounty program in 1876, and Ventura County and Santa Barbara County followed suite in 1883 and 1885, respectively. Santa Barbara County offered $5 for mountain lions, $2.50 for coyotes, and $1 for bobcats. To collect the bounty, coyote hunters were required to bring in the scalp (including nose and ears) of the coyote to the County office. After a few months, the bounty was cancelled after $50,000 had been paid out to bounty collectors, then reinstated again in 1889 at a rate of $15 per scalp.

In 1891, coyote bounties were so successful that they risked bankrupting county coffers, so the state stepped in an offered a statewide coyote bounty of $5 for each coyote killed. The new law stated: “Any person who shall kill and destroy any coyote or coyotes, in any county in this State, after passage of this Act, shall be paid a bounty of five dollars, out of the general fund in the State Treasury, for each coyote so destroyed.”

In just a few short months, the program was so successful that a newspaper article referred to the “coyote industry” and warned that it could bankrupt the state. The program suffered from widespread fraud. Sometimes, the same coyote scalps would be submitted to several counties, while other scalps were shipped into California from neighboring states where coyotes were even more numerous. “Coyote farms” would breed coyotes solely to kill them and collect bounties. The state bounty program was eventually cancelled amidst financial ruin.

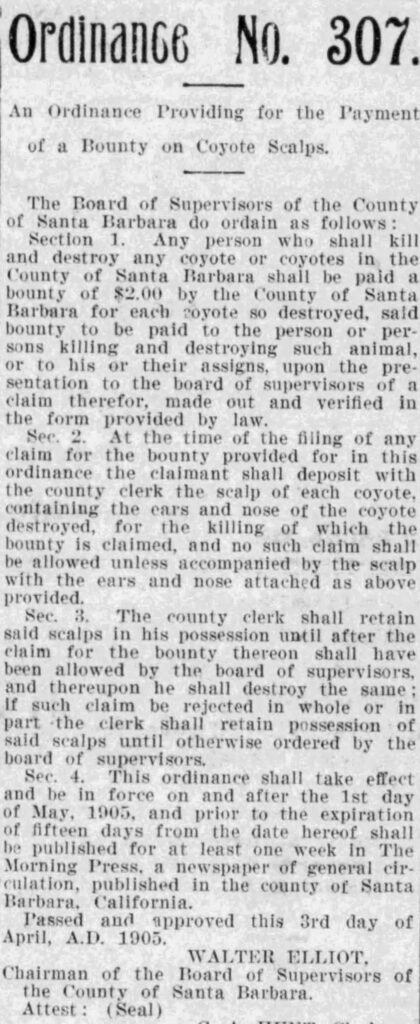

Coyote bounties were prevalent throughout the central coast in the early 1900s. The Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors in 1905 unanimously voted to offer a $2 bounty (around $70 in today’s dollar) to anyone turning in a coyote scalp.

The bounty was reissued in 1911 and again in 1912. The headlines in the Santa Maria Times read “Shoot Coyotes and Get Rich,” and that’s exactly what happened. In just one month (December 1912), a whopping 424 coyote scalps were turned in to the County. The program quickly became a financial drain on the County’s coffers, and concerns arose that perhaps some scalps were being collected from outside of the County and imported by those hoping to cash in. A reporter for the Santa Maria Times in 1913 wrote:

“Should it appear to the supervisors that the drain becomes too strong it is believed in time the bounty may cease, but the stockmen and farmers of the county will have the satisfaction of knowing that the enemy to their poultry yard and to much of the young stock on their ranches has been done away with and the number of coyotes at the present time in the county has been reduced at least one half in the few months the bounty has been in effect.”

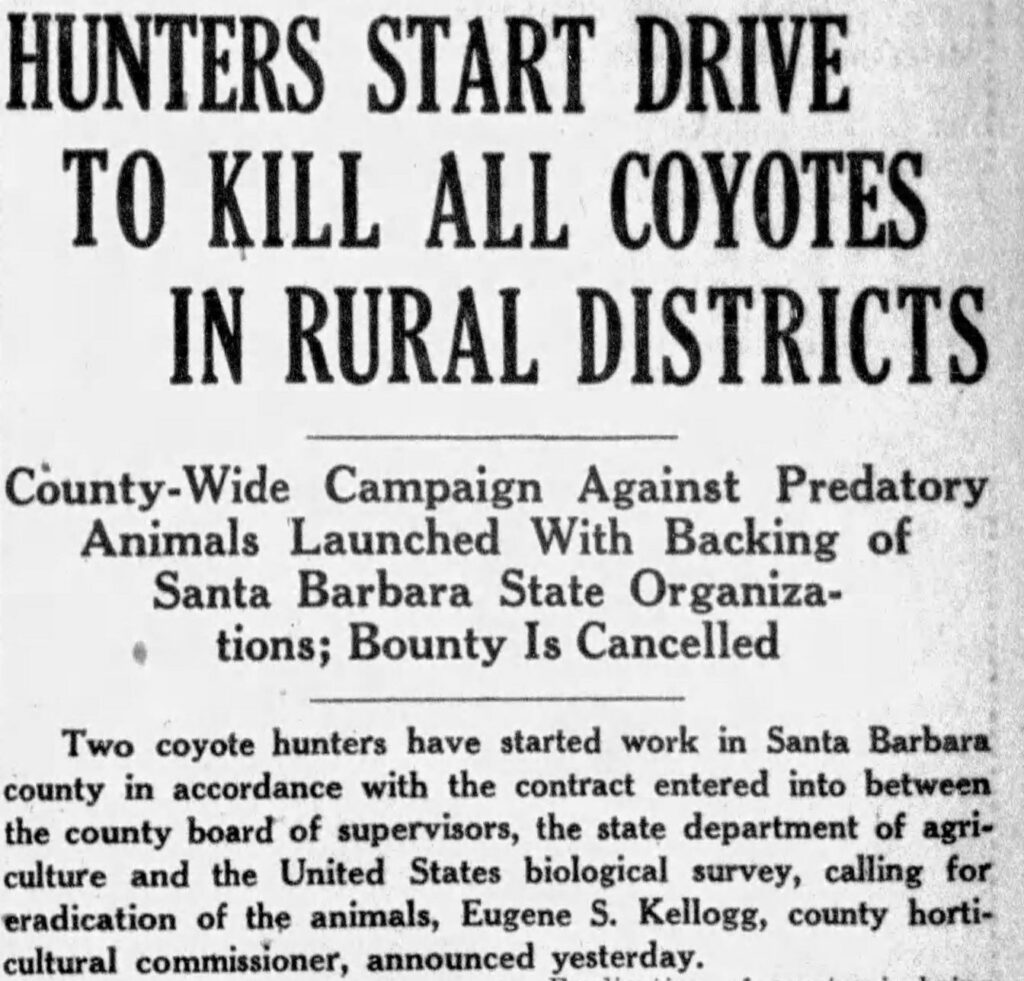

Despite the costs associated with the bounty program, pressure remained strong to continue coyote eradication programs, even increasing the amount of the bounty to $5 per coyote in 1918. The result, reported one local newspaper, was a “great war on coyotes across the county” costing as much as $4,000 per month. The bounty program was cancelled (again) because it was too expensive, yet it was reinstated again in 1920 and again in 1924. Bounties fell into disfavor in the years following as County leaders preferred hiring government-sponsored mercenaries to kill coyotes.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the County again shifted between offering bounties and hiring paid exterminators. County leaders also experimented with programs offering landowners free poison for coyotes. All told, tens of thousand of coyotes were exterminated in Santa Barbara County alone during this period, yet the coyote continued to survive and persevere.

Some states, such as Utah, still offer bounties, but California does not. While bounty programs are no longer in place today, coyotes receive no legal protections in California. They can be hunted year-round with a hunting license, with no limit (unlike other mammals, which can only be hunted during certain seasons and with bag limits). A federal agency under the Department of Agriculture known as “Wildlife Services” continues to contract with counties to eradicate coyotes. In 2022, USDA Wildlife Services killed 56,010 coyotes across the country, including 3,209 in California.

Coyotes in Native Culture

Tribes throughout the region have deep ties to coyote in their stories and culture. In stories shared by the Chumash, the coyote appeared most frequently and plays a central role in Native storytelling, often as a hero or a trickster. Coyotes appear in many stories as symbols of human nature.

In one traditional Chumash story, Coyote rescues a boy named Hawk from the Santa Barbara Channel after he fell from a canoe while fishing. Coyote’s powers are tested by Swordfish as the boy is eventually rescued. When they return to the village, a huge feast is held in Coyote’s honor.

Two excellent books recount these stories: for adults, December’s Child: A Book of Chumash Oral Narratives and for young adults, When the Animals Were People.

Protecting Coyotes

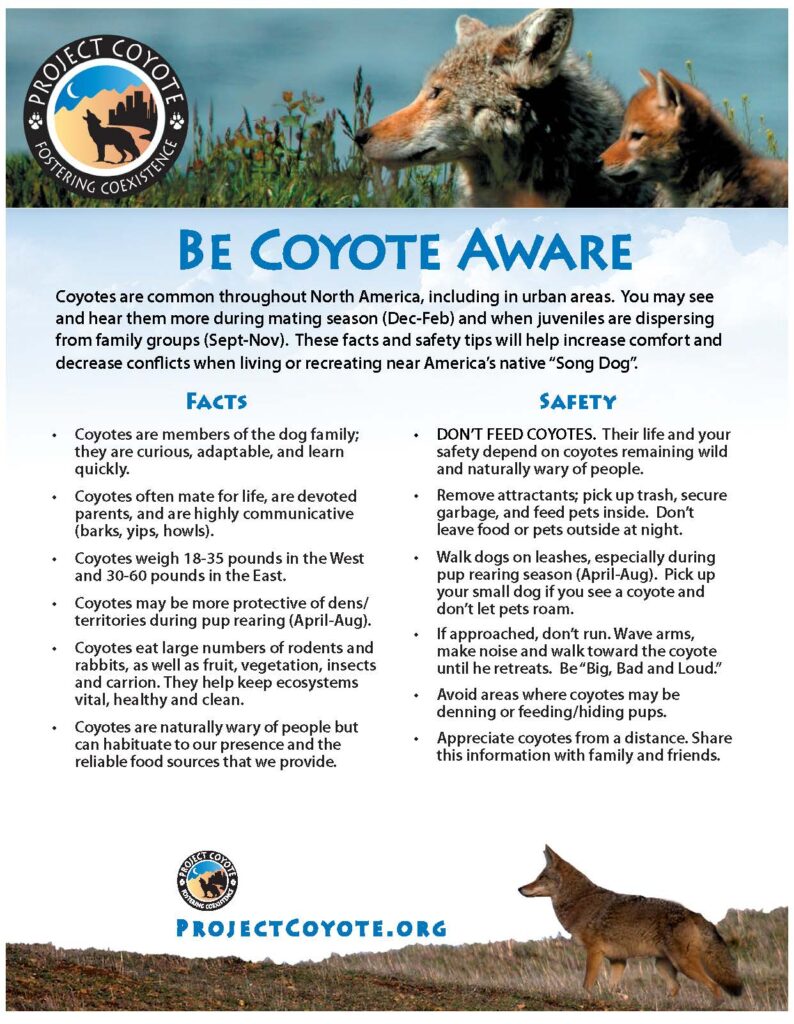

Amidst all they’ve endured, coyotes are a symbol of survival and tenacity. History tells us that the most effective way for humans to coexist with coyotes is to respect their habitat and take simple steps that can minimize conflicts. Our friends at Project Coyote have designed a useful flier in English and Spanish to help us all be more coyote aware.