Falco peregrinus anatum

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

- Fully Protected – California Department of Fish and Wildlife

The American peregrine falcon can be seen soaring high in the sky throughout the Los Padres National Forest. These magnificent birds have wingspans up to 44 in (almost 4 feet!) and fly at speeds up to 60 mph. When diving down (a.k.a, “stooping”) for their prey, they can top speeds of over 200 mph, making them the fastest animal that inhabits the Los Padres. They are very efficient predators. By using their large talons, they are able to masterfully grab and/or strike their prey in mid-air, then use their unique notched beak to bite through the neck to kill it. They do enjoy a challenge though, because their prey consists of other highly-mobile birds and sometimes bats.

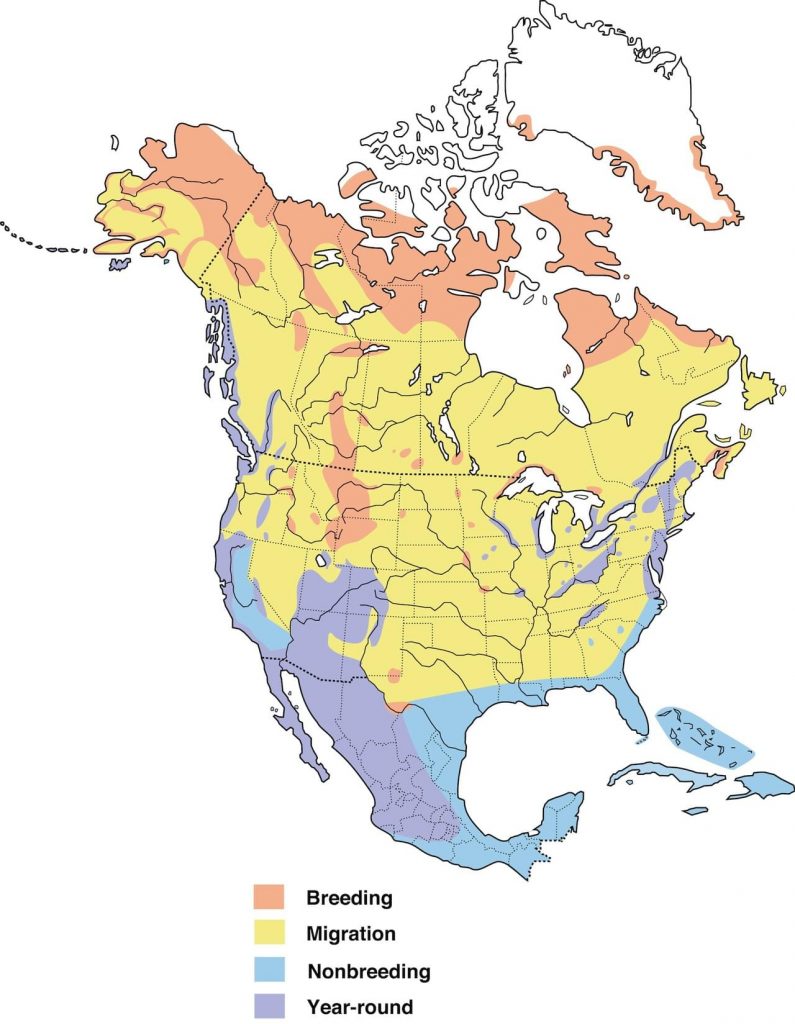

There are 18 subspecies of peregrine falcon, which together have a global distribution, occurring on all continents except Antarctica. The subspecies of American peregrine falcon inhabits North America, from Mexico to Canada. Although some American Peregrine falcons will migrate, falcons in California tend to remain in the same region year-around. Historically, they occurred throughout California but are now mainly located in the central and southern coast. Their population is expanding though, with hopes of the historical range being fully restored.

American peregrine falcons begin their breeding season in February, which lasts through June. During this season, the males will become territorial and highly protective of their nest sites. The females normally lay four eggs, typically in March. Both the male and female help keep the eggs warm and healthy by incubating them for 29–33 days. In California, fledging occurs in late May or early June. Juveniles will start hunting on their own and claim their independence about 6–15 weeks later.

The Los Padres National Forest contains the peregrine falcon’s woodland, forest, and coastal habitats. Here they enjoy the “high life” by nesting upon ledges and small caves of high vertical cliffs. They usually nest around 4,000 ft. elevation but have been found at upwards of 10,000 ft. elevation. Occasionally they nest in trees and tall buildings as well. They especially enjoy homes with a view, particularly a panoramic view of open country which contains an abundance of the other birds that they prey upon.

Threats and Conservation

Prior to the 1940s, the American peregrine falcon was estimated to have over 3,875 nesting pairs throughout North America. However, the populations of peregrine falcons and other top predators began quickly declining through the middle part of the century. By the early 1970s, no more than 5-10 pairs remained in California. Their decline is attributed to synthetic organochlorine pesticides (especially the commonly known one, DDT). DDT is not excretable, meaning once ingested or exposed to it, it remains in fat tissue and accumulates over time until it reaches lethal levels. DDT reduced the amount of calcium in peregrines falcons’ eggshells, making them thin and prone to lose moisture and early cracking. The result of DDT exposure was that fewer chicks were surviving every year.

Because of steep declines, the American peregrine falcon was one of the first species classified as “Endangered” under federal law in 1970 (before the modern-day Endangered Species Act). The use of DDT was subsequently banned the United States in 1972. Experimental captive-release programs (breeding falcons in captivity then releasing them) proved successful at increasing nesting pairs, with more than 6,000 falcons released since the program started. The banning of DDT, coupled with these captive-release programs, allowed the peregrine falcon to repopulate its historic range. By 1998, it was estimated that 1,650 pairs were in North America, and the following year, the peregrine falcon was removed from the federal endangered species list.

The American peregrine falcon is one of the 22 species that have been delisted under the Endangered Species Act because of successful population recovery. It was delisted on August 25, 1999 and its population is believed to still be growing. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service will conduct population surveys every three years and will consider placing the species back on the endangered list if population declines are detected. There are currently more than 3,000 peregrine falcon pairs in North America, so the population is continuing to grow and is an Endangered Species Act success story.

This species is still at risk to illegal shooting, illegal falconry activities, and habitat destruction. Because of these threats, the U.S. Forest Service still considers the peregrine falcon to be a “Sensitive Species,” giving the bird added protection as it continues on the path of recovery. The conservation measure of highest concern on National Forest System lands is protecting cliff-nesting sites from human disturbance, particularly during the nesting season. Additionally, the protection of riparian areas to maintain prey abundance is of importance to the falcon, too.