Last month, the Forest Service announced a rulemaking process that could create new protections for mature and old-growth forests (MOG) across the country. The announcement came on the heels of the Biden administration’s release of a national inventory of MOG forests. Both the inventory and the new rulemaking stemmed from an executive order issued last year.

It may seem obvious, but MOG forests are important considering their contribution to carbon storage and wildlife habitat. In western dry conifer forests, large trees may make up less than 3% of all trees but contain up to 42% of all carbon in a given forested area. And species such as the California spotted owl require dense, old forests for nesting.

The federal inventory identified nearly 113 million acres of MOG forests across national forests and lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management, which was about twice as much as identified by a recent independent study. Other recent analyses have also found that far fewer acres of federal forests should be considered mature or old-growth, but these discrepancies ultimately come down to how MOG is defined and whether inventories include Alaska.

For example, the federal inventory included certain ecosystems—such as pinyon-juniper woodlands—that are typically not classified as forests at all. Much of the MOG forest identified by the Biden administration is in the form of pinyon-juniper, especially in the Intermountain West. Debate about what to classify as a forest and which forests should be classified as MOG will undoubtedly continue.

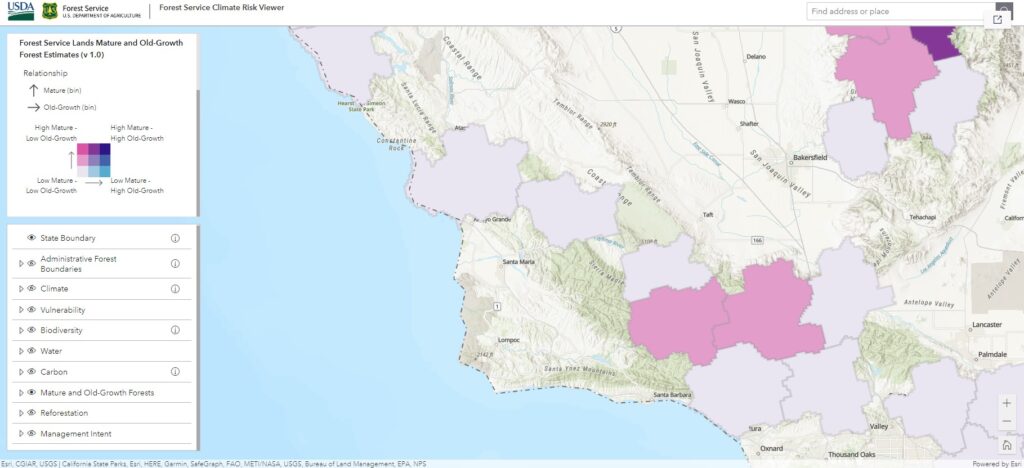

While the Forest Service’s report on MOG forests on national forest lands contains useful information, the actual data have not been made available to the public. Instead, we have been directed to a vague interactive map to see where MOG forests are, but the extremely coarse scale of the map render it somewhat useless for taking a close look at particular areas within a single national forest like the Los Padres. In fact, the report and the map make it unclear whether the Forest Service identified any lands within the Los Padres National Forest as old-growth.

Only the general areas around Mt. Pinos and Big Pine Mountain are indicated to have some mature forest and low amounts of old-growth. This is surprising considering the lack of historical logging across most of the Los Padres National Forest, the presence of obvious old-growth forest in places like the Sespe Wilderness and Chumash Wilderness, and the extensive pinyon-juniper landscapes of northern Ventura County that are comprised of relatively large singleleaf pinyon pines (which grow very slowly). Even in the Big Sur region, where there are numerous stands of old coast redwoods, the Forest Service’s map shows only “Low Mature – Low Old-Growth.”

Interestingly, the agency recently claimed that there is no evidence of old-growth forest on Pine Mountain. We have analyzed forest stand exam data, historical records, and aerial imagery from the 1930s and can find no evidence that logging historically occurred on Pine Mountain. The presence of conifers up to five feet in diameter, multilayered canopies, high tree species diversity, a variety of tree ages, and the presence of old snags (i.e. standing dead trees) and downed wood would indicate that there is indeed old-growth forest there, yet the agency apparently disputes this with virtually no evidence to back up their claims that the forests on Pine Mountain are actually quite young.

All of this is to say that the Biden administration’s methods are somewhat opaque and confusing.

Regardless, the federal rulemaking process currently underway presents an important opportunity for scientists, tribal groups, conservation organizations, and the general public to weigh in about how best to protect MOG forests. Yet, the government appears to be avoiding an elephant in the room: its ongoing logging practices. The report released last month does not identify logging as a threat to MOG forests, instead focusing on fire, insects, and drought as primary concerns. Based on many indications over the past few years as well as continued approval of projects that allow cutting of large trees, there’s reason to believe that the Forest Service will attempt to bake logging under the guise of wildfire mitigation and “forest health” into future MOG forest management policies.

A 2023 study by a team of independent scientists from the Woodwell Climate Research Center, Wild Heritage, and the Natural Resources Defense Council found that 16 inches represents the average diameter threshold that separates smaller trees from larger trees in the conifer forests of the Sierra Nevada. These forests are slightly wetter than those of the Los Padres National Forest and therefore have higher growth rates, so a 16-inch diameter tree in the Sierra Nevada may be even younger than a tree of the same size in the Los Padres. Yet, the Forest Service has proposed and approved multiple projects that allow trees up to two feet in diameter or more to be cut, stating that anything smaller than 24 inches in diameter is a small tree.

We’re joining a chorus of organizations in asking the Biden administration to establish meaningful protections for federal MOG forests, especially as it relates to logging. Big trees, both live and dead, play an outsized role in carbon storage in our forests. If the current administration is uplifting natural climate solutions, then protecting large trees from harvest will be important over the coming years and decades.

Stay tuned for more information about this issue and how you can get involved.

Comments are closed.