Bakersfield, CA — Today ForestWatch and partner Center for Biological Diversity sued the Trump administration to reverse its approval of what would be the first new oil well and pipeline in Carrizo Plain National Monument since it was established in 2001.

The legal action also seeks to resolve the fate of other long-dormant wells and associated facilities that the Bureau of Land Management identified for possible removal in 2013.

Click here to support this effort with a donation to our Carrizo Plain Defense Fund.

The Bureau originally approved the well and pipeline in 2018 but withdrew that approval last year after Los Padres ForestWatch and the Center for Biological Diversity filed objections. The conservation groups cited the well’s potential harm to wildlife, views and the climate.

In May the Bureau reapproved the project, continuing to disregard significant environmental harms. The proposed fossil fuel extraction would harm threatened and endangered wildlife, mar scenic views and violate several laws, including the Endangered Species Act and National Environmental Policy Act, as well as the monument’s resource-management plan.

The proposed well site is located at the base of the Caliente Mountains, inside the western boundary of Carrizo Plain National Monument. The area is home to several protected species, including threatened San Joaquin antelope squirrels, endangered San Joaquin kit foxes and an endangered flowering plant called the Kern mallow.

The well would be drilled on a pad that hasn’t produced oil since the 1950s. In 2016 the Bureau agreed to the oil company’s request to abandon the old well, pipelines and other equipment at the site. The company, E&B Natural Resources, was supposed to restore the area to its natural condition, including recontouring and reseeding. The work was never done.

The Bureau’s approval of new development backtracks on plans to restore the land. The monument’s management plan calls for phasing out oil drilling in the national monument, including promptly capping and remediating old wells and facilities that have not produced oil in decades. Some of the oil wells in Carrizo Plain National Monument have sat dormant since the 1950s, potentially emitting greenhouse gasses, leaving a blight on the landscape and posing a risk to underground water supplies.

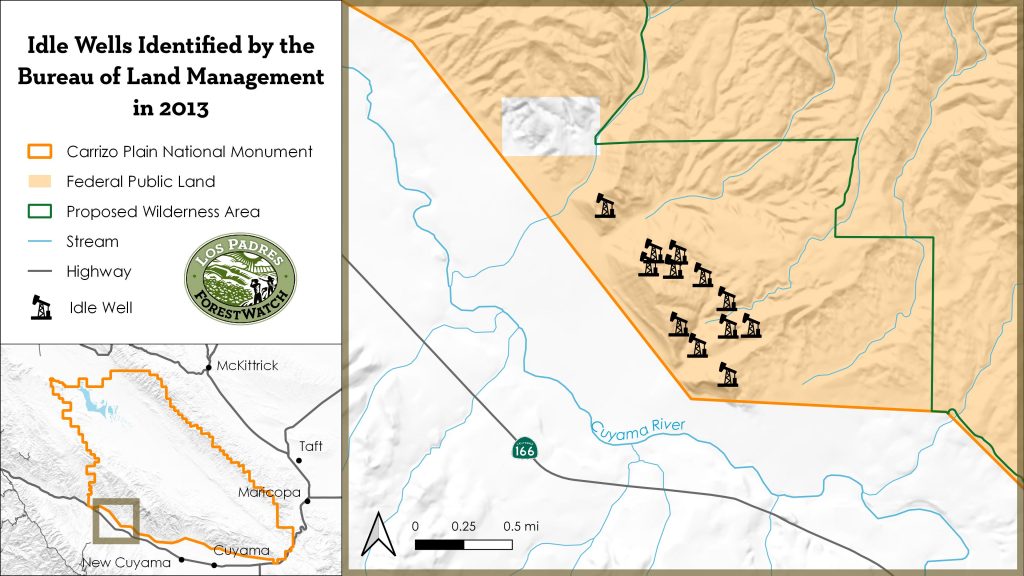

The groups’ lawsuit calls for a plan to properly abandon and reclaim old well sites owned by E&B Natural Resources. In 2013 the Bureau and the oil company began evaluating 12 idle wells in the Carrizo Plain to determine whether they should be permanently plugged and the surrounding land restored to natural conditions. Seven years later only one of the wells has been addressed. The Bakersfield-based oil company has a history of spills and violations across California.

Today’s lawsuit centers on the Russell Ranch Oil Field, which covers approximately 1,500 acres of the Carrizo Plain National Monument and adjacent private land. In 2018 the field produced only 128 barrels of oil per day―0.03% of the state’s total oil production and one of the lowest-producing oilfields in the state. The field is reportedly nearing the end of its useful life.

The lawsuit was filed in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles. The groups are represented by the Center for Biological Diversity and the Stanford Environmental Law Clinic.

About the Carrizo Plain

Carrizo Plain National Monument is a vast expanse of golden grasslands and stark ridges known for their springtime wildflower displays. Often referred to as “California’s Serengeti,” it is one of the last undeveloped remnants of the southern San Joaquin Valley ecosystem.

The Carrizo Plain is critical for the long-term conservation of this dwindling ecosystem, linking these lands to other high-value habitat areas like the Los Padres National Forest, Salinas Valley, Cuyama Valley and Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge in western Kern County.

Honoring the area’s high biodiversity, limited human impacts and rare geological and cultural features, the Carrizo Plain was declared a national monument in 2001. It includes more than 206,000 acres of public lands―perhaps the largest native grassland remaining in all of California.

Comments are closed.