San Luis Obispo County – On August 13, 2024 Los Padres ForestWatch, San Luis Obispo Coastkeeper, California Coastkeeper Alliance and Ecological Rights Foundation filed a lawsuit for violations of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in federal district court against the County of San Luis Obispo for operating Lopez Dam in a manner that is driving threatened species to extinction.

For the past 30 years, the County has known about the harm its operation of Lopez Dam is causing to endangered species in Arroyo Grande Creek. In 1994, a citizen complaint was filed alleging that the County was violating the law by failing to release enough water from Lopez Dam for endangered fish in Arroyo Grande Creek below the dam. The State Water Resources Control Board then warned the County that it would not renew its water rights permit until the County’s operations were in line with the ESA. Three decades later, the County remains out of compliance.

In 2004, the County made initial efforts to come into compliance by drafting a planning document outlining protective measures for endangered Steelhead and California Red-Legged Frogs, but it was rejected by federal agencies for being inadequate. Recently, the National Marine Fisheries Service confirmed that the County has still not taken the necessary steps to restore Steelhead populations and remains out of compliance with the law.

To remedy the thirty years of ongoing ESA violations, the Plaintiffs in this case assert that the County must, first and foremost, ensure the release of sufficient flows of water from Lopez Dam at specific times of the year to support complex life cycle needs of wildlife. The County must also include provisions for securing fish passage past Lopez Dam so that Steelhead can access historic spawning grounds in the headwaters of Arroyo Grande Creek in Los Padres National Forest, and commit to other essential upstream and downstream habitat enhancement needs for endangered species.

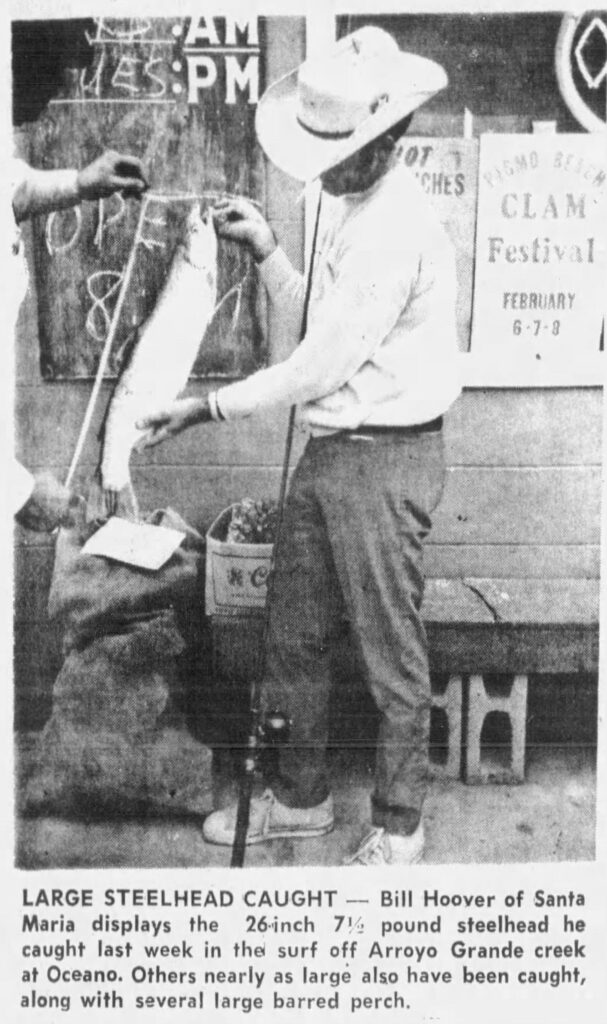

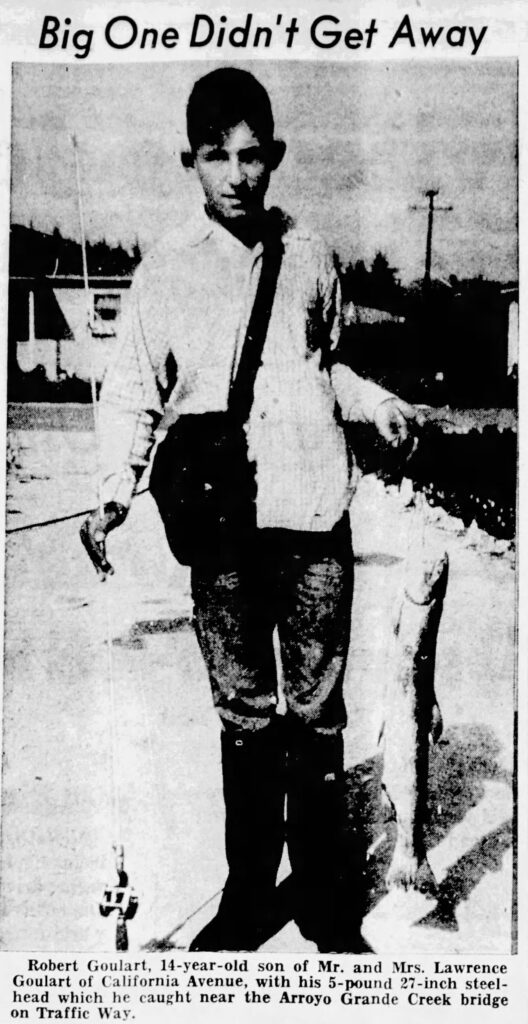

Steelhead are a keystone species for the San Luis Obispo region. In the 19th Century, the San Luis Obispo and Santa Ynez regions supported the largest runs of Southern steelhead throughout their range, likely between 20,000 to 30,000 adults per year. A page in Robert A. Brown’s The Story of the Arroyo Grande Creek describes how “steelhead would fill the creek as they propelled their great silvery bodies inland.” Trophy-sized, caught steelhead trout were regularly featured in local media outlets such as the Santa Maria Times through the 1940s and 50s.

Steelhead trout are also an important cultural resource. These fish were a critical food source and still an important symbol to the Chumash people. For thousands of years the Chumash and Salinan people coexisted with steelhead and honored the fish which they fondly called “Isha’kowoch”. Mexican and Spanish immigrants spread word of steelhead during the California goldrush. And by the early 1900s steelhead had become a popular game fish, and fisherman would flock from all over during the winter months to capture giant steelhead.

In recent decades, however, the number of adult anadromous steelhead has declined significantly, to the point that it is now rare to see them in the wild. Steelhead abundance has declined precipitously from a historic high of roughly 25,000 returning adults to fewer than 500 adults. Arroyo Grande Creek, the creek below Lopez Dam, has only about 20 percent of historical estuarine habitat remaining and there have been similarly large losses of Steelhead throughout the fish’s range. Despite these losses, Arroyo Grande Creek and its tributaries have been identified by federal and state resource agencies as essential—so-called “Core 1”—habitat for the survival and recovery of South-Central California Coast Steelhead.

Comments are closed.