From our beginnings in 2004, Los Padres ForestWatch has worked tirelessly to protect the Los Padres National Forest and other public lands throughout California’s central coast region. We’ve built a solid track record of success over the years, becoming one of the most effective community-supported conservation groups in the country. And we couldn’t have done it without our members, volunteers, and supporters who have been with us every step of the way.

Join us as we look back at what we’ve accomplished together.

Quick Navigation

Defended Bears in SLO County

Protected the Carrizo Plain National Monument

Safeguarded Pristine Roadless Areas

Prevented Commercial Logging in the Los Padres

Preserved Public Access to Matilija Falls

Banned Unmanaged Target Shooting

Stopped Drilling on the Carrizo Plain

Stopped Oil Development Along Forest Boundary

Kept Fracking Out of the Los Padres

Defended Solitude Along Scenic Highway 33

Ended Overgrazing on an Ecological Reserve

Kept Our Local Public Lands Beautiful

Protected the Gaviota Coast

Protected Wildlife Habitat

Protected 52,075 Acres of Forest Land From Oil Drilling

ForestWatch’s landmark accomplishment is stopping a 2005 plan to expand oil drilling across more than 52,000 acres of the Los Padres National Forest. The drilling plan targeted areas adjacent to several protected wilderness areas, habitat for endangered plants and wildlife, popular recreation areas, and scenic gateways that the public uses to access the forest—all for less than a single day’s supply of oil.

While less than a year old, ForestWatch sprang into action. We joined forces with the Center for Biological Diversity and Defenders of Wildlife, serving as lead author of a 92-page appeal we filed with the top forest official in California. After our appeal was denied, we filed a lawsuit in federal court in 2007. That case is still pending, and the Forest Service agreed in 2016 to delay the plan indefinitely.

Defended Black Bears in SLO County

ForestWatch and our partners defeated a scientifically-unsound proposal to open the first-ever hunting season for black bears in San Luis Obispo County. The hunt was first announced in 2009, even though state wildlife officials didn’t know how many bears resided in the county nor whether a hunt would be sustainable. Hundreds of residents wrote letters, urging state wildlife officials to conduct a scientifically-defensible population survey.

In response to overwhelming public outcry, officials cancelled the 2009 hunt. But the proposal was resurrected a year later after officials estimated 1,067 bears lived in the County. ForestWatch teamed up with the Humane Society of the United States, wildlife attorney Bill Yeates, and Dr. Rick Hopkins—one of the state’s most preeminent bear biologists—to demand that the Department undertake a scientifically-defensible population survey based on genetic sampling. The Department then cancelled the 2010 hunt and agreed to undertake a more thorough count of black bears in San Luis Obispo County. That study concluded that the County’s bear population was 90% smaller than initial estimates and that bear hunting would not be sustainable. Due to ForestWatch’s leadership on this issue, bears are safer and biologists now have a better understanding of bear populations in SLO County.

Kept the Carrizo Plain a Monumental Landscape

In 2017, the Interior Department launched a review of more than two dozen national monuments across the country to determine whether to reduce the size of these protected areas or eliminate their protections entirely. The Carrizo Plain National Monument—a 200,000-acre expanse of grasslands and stark ridges adjacent to the Los Padres National Forest in San Luis Obispo County—was listed as one of the monuments on the chopping block.

ForestWatch immediately mobilized to defend this iconic landscape. We built a coalition of nearly two hundred local businesses, museums, elected officials, community leaders, scientists, chambers of commerce, archaeological societies, trail groups, and Native American tribes to speak with a unified voice for the protection of this unique landscape. We launched a website and gathered and hand-delivered more than three thousand letters to the Interior Department’s headquarters in Washington DC. As a result of our efforts, the Carrizo Plain’s protected status remains untouched.

Secured Better Protections for Roadless Areas

The Los Padres National Forest contains more than 600,000 acres of roadless lands that are eligible for wilderness protection but have not yet received formal wilderness designation from Congress. The management of these lands—and the levels of development allowed within them—are set forth in the Land Management Plan for the Los Padres National Forest.

The U.S. Forest Service updated this management plan in 2012 but refused to recommend any new wilderness protections for these pristine roadless areas. ForestWatch and our allies helped generate more than 10,000 comments from residents urging forest officials to strengthen protections for roadless areas. We crafted our own detailed 43-page technical comment letter, filed a formal objection when our concerns went unaddressed, and negotiated an agreement with the Forest Service to increase the level of protection for roadless areas to better protect them from roadbuilding and motorized use. As a result, sixteen roadless areas totaling 293,000 acres now receive stronger protections from development.

One of these roadless areas—the De La Guerra Roadless Area between Figueroa Mountain and Ranger Peak—has been under repeated threat from a massive road-building scheme. These roads were proposed as part of a commercial livestock grazing operation in the area. Through a series of letters, appeals, lawsuits, and negotiations, the Forest Service in 2016 agreed to remove seven miles of existing roads from this area to better protect its roadless character. Also at our urging, forest officials agreed to undertake a multi-year study to better understand how grazing impacts oak tree recruitment.

Protected Forests From Commercial Logging

In the Los Padres National Forest, giant century-old trees rise above the surrounding chaparral vegetation in a series of “sky islands” that provide important wildlife habitat and unique places to visit.

One of our first victories came in 2005, when ForestWatch sounded the alarm on a proposal to remove large old-growth trees from several mountaintops across the forest, including Figueroa Mountain, Frazier Mountain, Pine Mountain, Mount Pinos and Cerro Noroeste. Forest officials initially tried to fast-track these projects via commercial timber sales, but ForestWatch convinced them to prepare detailed environmental studies. Ultimately, based on those studies, the Forest Service adopted an alternative approach that protected large-diameter trees for future generations, without relying on commercial logging. Three of the logging projects were cancelled entirely, and the remaining projects were completed in a way that kept these forests intact.

ForestWatch secured a precedent-setting courtroom victory in 2008, protecting Grade Valley and Alamo Mountain in northern Ventura County from a salvage logging project. The Day Fire had passed through this part of the Los Padres National Forest, and the Forest Service proposed allowing timber companies to bring heavy equipment into this fragile burn area to remove “dead and dying” trees across more than 1,200 acres. Officials approved the plan without first preparing a standard environmental assessment, and targeted many trees for removal that were still alive and recovering from the effects of wildfire. After arguing our case in U.S. District Court, the judge ruled in our favor, allowing the area to heal from the effects of wildfire without further damage caused by logging equipment. The case—Los Padres ForestWatch v. U.S. Forest Service—continues to serve as important caselaw for protecting post-fire landscapes and was recognized as one of southern California’s top five environmental achievements.

Currently, ForestWatch is working to protect old-growth forests across Tecuya Ridge, Cuddy Valley, Pine Mountain, and Mt. Pinos in the Los Padres National Forest. These areas have been targeted for logging, leading to two legal cases already.

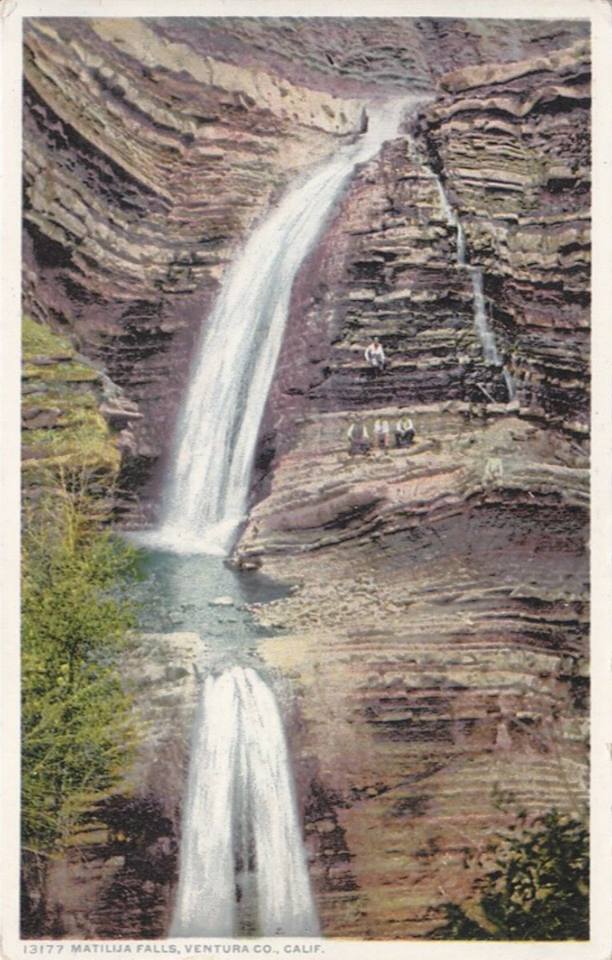

Preserved Public Access to Matilija Falls

For nearly a century, the public has traveled along a popular route leading to swimming holes, unique geologic formations, and the beautiful Matilija Falls in the Matilija Wilderness Area of the Los Padres National Forest near Ojai. But in 2009, an adjacent landowner began discouraging the public from using the area. ForestWatch formed an association of several local organizations and trail users and began negotiations with the landowner. After years of little progress, the association—known as Keep Access to Matilija Falls Open—filed legal documents in 2015, asking a judge to declare a permanent public easement through the property so that the public could continue to access the falls in perpetuity.

Based on longstanding California law dating back to the 1850s and affirmed several times by the California Supreme Court, a public right-of-way exists if five or more years of continuous public use can be shown predating 1972. As a result of our legal efforts, the landowner agreed to establish a permanent public easement across his property so that current and future generations can continue to enjoy this corner of the Los Padres National Forest.

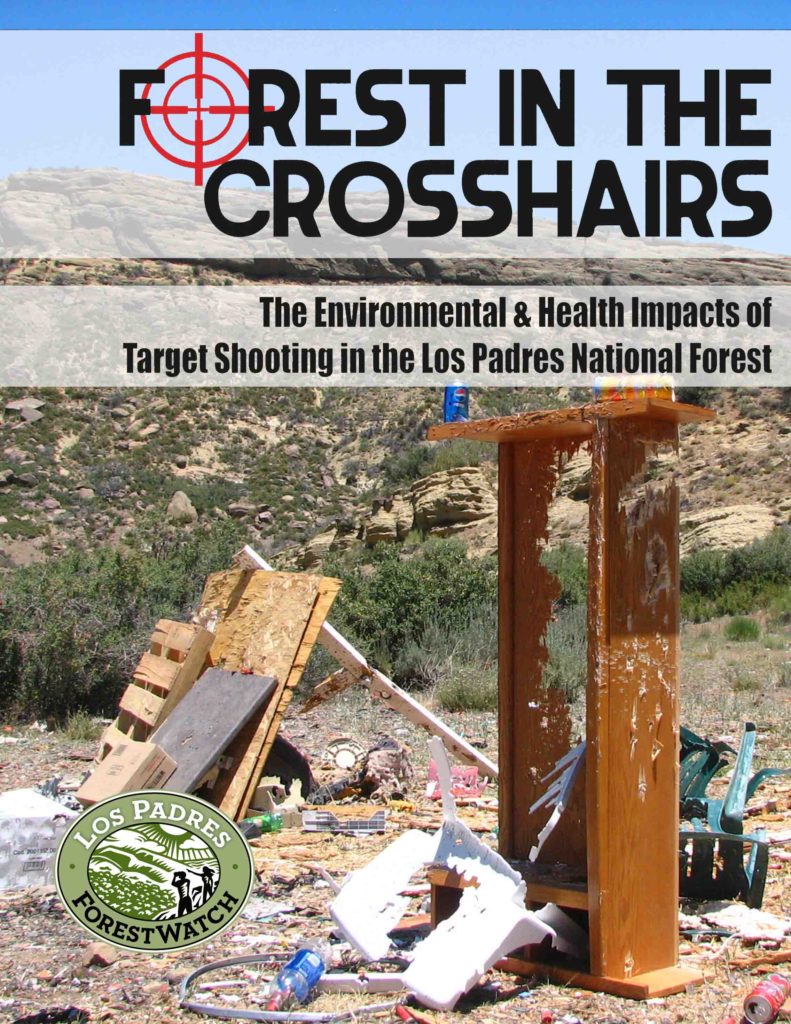

Banned Unmanaged Target Shooting

A ban on “dispersed” target shooting in the Los Padres National Forest was first adopted in 2005, when the Forest Service updated its management plan for the area. But in the decade following, the ban was not implemented. A 2016 report by ForestWatch found nearly one hundred informal shooting sites throughout the forest. The report—Forest in the Crosshairs: The Environmental and Health Impacts of Target Shooting in the Los Padres National Forest—revealed large amounts of trash at these sites, along with dozens of trees left dead or dying from repeated shooting. Televisions, computer monitors, refrigerators, microwaves, and other household appliances were frequently used as targets, contaminating nearby soils and waterways with toxic heavy metals. Shooting-related vandalism was also recorded at public restrooms and trailhead signs, costing tens of thousands of taxpayer dollars to repair.

The Forest in the Crosshairs report also noted that target shooting has caused at least 53 wildfires in the Los Padres National Forest during the past 25 years, scorching a combined 74,478 acres of forestland according to official Forest Service data.

The Forest Service refused to implement its own target shooting ban, so ForestWatch filed suit in 2018. As a result of the lawsuit, the Forest Service agreed to ban unmanaged target shooting throughout the Los Padres National Forest.

Stopped Drilling in The Carrizo Plain

In 2011, an oil company proposed to construct a new well and pipeline inside the boundary of the Carrizo Plain National Monument at the base of Caliente Mountain. The Interior Department approved the well in 2018, and ForestWatch—along with our partners Center for Biological Diversity—appealed the approval and requested full review by the top Interior official in California. Earlier this year, the state director upheld our appeal, overturned the approval of the oil well, and sent the matter back to the drawing board.

It’s not the first time that the National Monument was threatened by oil drilling. In 2006, an oil tycoon filed plans to explore for oil on 3,500 acres inside the Carrizo Plain National Monument. After ForestWatch demanded preparation of a full environmental impact study, the oil company withdrew its plans and the oil leases expired. The area is now forever protected from future oil development.

And in 2008, another oil company filed plans to explore for oil along a five-mile stretch of the Carrizo Plain National Monument’s valley floor, an area known for its stunning wildflower displays and endangered wildlife habitat. The oil company planned to use dynamite and “thumper trucks” to send shockwaves through the fragile ecosystem, and to possibly drill several exploratory oil wells to determine the extent of oil deposits in the area. ForestWatch led a coalition of ten local and national conservation groups, sending a letter to Interior officials demanding preparation of a full environmental study. The oil company eventually withdrew its plans to explore for oil on the valley floor.

Stopped Oil Development Along the Forest Boundary

ForestWatch united with rural landowners to protect our forest—and their homes—from oil development. Joining with Cuyama Valley residents, we protected more than 10,000 acres from a controversial oil lease sale in 2006. Our pressure forced the Interior Department to change their state-wide policy, requiring environmental assessments to be prepared prior to auctioning off federal lands for oil leasing. No federal lands adjacent to the forest have been placed on the auction block since then.

In 2007, Upper Lopez Canyon residents contacted ForestWatch for assistance after oil companies began knocking on their doors in this rural area of San Luis Obispo County. We brought canyon residents together, telling the oil industry with a unified voice that drilling was not acceptable in the pristine canyon. The oil industry left the area and we have not heard from them since.

In 2014, the Ventura County Planning Commission approved an oil company’s request to reopen a long-abandoned oil field adjacent to the Los Padres National Forest near Lake Piru. We appealed the decision to the County Board of Supervisors, and on the eve of the hearing, the oil company withdrew the project.

In 2018, ForestWatch defeated an attempt to eliminate the public’s right to participate in oil drilling and fracking decisions throughout Ventura County. By preserving this cornerstone of democracy, people can continue to have a voice in protecting our public lands and surrounding communities from pollution.

Stopped Fracking in Los Padres National Forest

In 2014, ForestWatch successfully stopped three fracking operations in the Sespe Oil Field. The fracking was approved by local and state officials without any public hearing or environmental review. Our investigation revealed that the approval was issued erroneously, prompting the County of Ventura to cancel the permits. It was the first time in California that a fracking operation was halted due to public pressure.

ForestWatch discovered a fracking operation taking place on national forest land in 2013 and was the only member of the public able to gain access to document the controversial activity over several days. Shortly thereafter, ForestWatch released a report showing that thirteen wells had recently been fracked in the Sespe Oil Field. Under ForestWatch’s watchful eye, not a single well has been fracked since then, keeping the Sespe frack-free for six years and counting.

Defended Solitude Along Scenic Highway 33

Highway 33 is a National Forest Scenic Byway taking travelers on a winding, two-lane road through the heart of the Los Padres, bisecting some of the most spectacular and remote scenery in the region. When several new and expanded gravel mines threatened to send hundreds of semi-trucks per day along this dangerous route, ForestWatch spearheaded a community effort to keep our forest from becoming an industrial trucking route.

In 2007, ForestWatch organized a town hall meeting in Ojai, spawning the formation of the Stop the Trucks Committee and catapulting local residents into action. With the community’s support, ForestWatch convinced mine operators in Ventura County to prepare the highest level of environmental study before expanding their operations. Just a short year later, our diligent work stopped a proposed mine from sending 138 gravel trucks per day through the heart of the Los Padres. This precedent-setting agreement spurred two other mines not to send any trucks through the forest.

Ended Livestock Overgrazing in Carrizo Plain Ecological Reserve

In 2014, ForestWatch secured an end to commercial livestock grazing in the Carrizo Plain Ecological Reserve, a 30,000-acre wildlife preserve in San Luis Obispo County adjacent to the Los Padres National Forest and the Carrizo Plain National Monument. A ForestWatch survey in 2009 uncovered severe overgrazing across much of the Reserve, fencing in disrepair, trampled wetlands and springs, cattle trespassing into areas where the lease expressly prohibits grazing, and other unsatisfactory conditions resulting in severe environmental degradation of lands that were supposed to have been set aside for the protection of rare wildlife.

State officials renewed the grazing permit, allowing the overgrazing to continue unabated, prompting ForestWatch to take them to court. As a result of our legal action, state officials agreed to end grazing in the Ecological Reserve and embark on a multi-year management plan. The reserve has been given a respite from commercial livestock grazing for five years and state officials are currently finalizing a long-term management plan for the area.

Kept Our Local Public Lands Beautiful

ForestWatch started a formal volunteer program in 2007. Since then, we have organized 120 different volunteer projects throughout the Los Padres National Forest, Carrizo Plain National Monument, and other public lands in the region. Much of these efforts have been aimed at illegal target shooting sites in the Los Padres where we focus on removing microtrash that can be dangerous to endangered California condors. More recently, our volunteers have been focusing on lead removal at old target shooting sites. Hundreds of pounds of lead have been removed from sites across the Santa Barbara frontcountry and Ventura County backcountry over the last few years. We have also eradicated invasive plants, removed derelict fencing, and cleaned up illegal pot grows.

To date, ForestWatch has organized over 1,800 volunteers who have spent nearly 10,000 collective hours removing more than 32,000 pounds of trash, dismantling 15 miles of old fencing, surveying and eradicating invasive plants along 40 miles of streams, and cleaning up three illegal grow sites. Simply put, our local public lands would look quite different if not for the hard work of amazing volunteers over the years.

Protected the Gaviota Crest

In 2017, the Forest Service canceled plans to construct a massive fuel break in a remote corner of the Los Padres National Forest after ForestWatch and the California Chaparral Institute challenged the project in federal court. The project would have removed native chaparral habitat across a six-mile-long, 300-foot-wide corridor along the crest of the Santa Ynez Mountains along the Gaviota Coast, one of the crown jewels of Santa Barbara County. The area contains some of the most significant stands of Refugio manzanita, one of the rarest and most endangered manzanita species in California. The site was located far away from any structures, and would have diverted critical funds away from where they are needed most—directly adjacent to communities. Our action protected rare plants and scenic views while encouraging the Forest Service to devote more attention to remediating fire risk closer to communities.

Protected Wildlife Habitat Corridors

ForestWatch’s Room to Roam campaign played a leading role in the enactment of the state’s first program designed to protect the pathways that animals use to move between the Los Padres National Forest, the Santa Monica Mountains, and other core habitat areas throughout Ventura County. The ordinance protects mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, bears, and other wildlife, giving them safe passage across an increasingly fragmented and developed landscape.

Over the course of two years, we attended stakeholder meetings, provided testimony at hearings, gathered support from other wildlife and environmental organizations, and generated hundreds of comment letters urging a strong wildlife protection ordinance. Industry lobbying groups opposed the ordinance, but they were no match against the strong outpouring of community support for our region’s wildlife. The Ventura County Board of Supervisors approved the wildlife corridor ordinance in early 2019, and ForestWatch is currently helping protect these protections in court.