Note: As new fires start and others continue to grow, some of the data presented below will change over the coming days and weeks. Updates will be provided when possible.

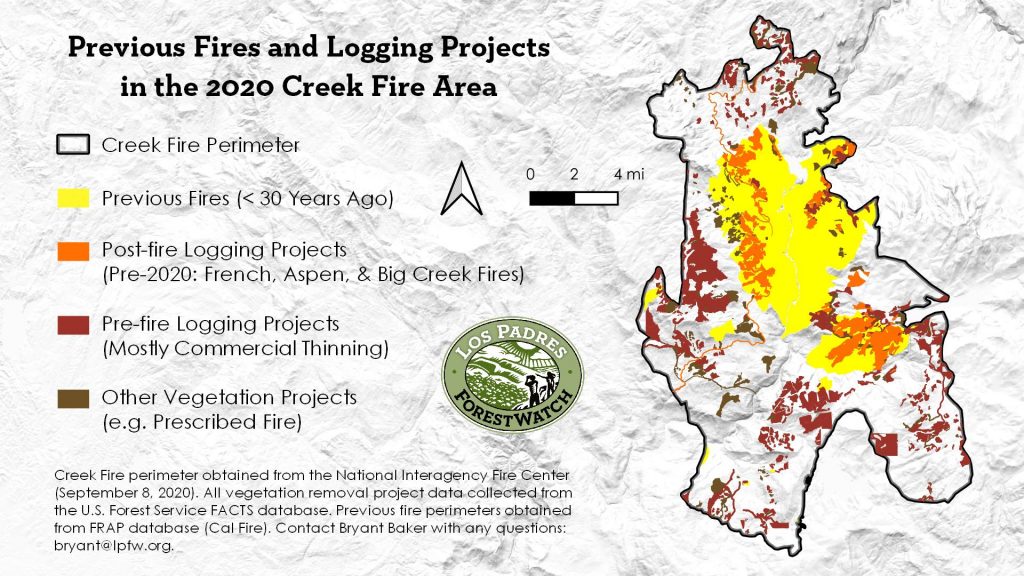

Update (Sept. 8): New wildfires developed over the Labor Day weekend due to another extreme heatwave and several human-caused ignitions. Most of the acreage burned this year is still in non-forested areas (chaparral, oak woodland, etc). However, eyes are now on the Creek Fire burning in the Sierra National Forest east of Fresno. Importantly, this is a heavily managed forested area that has had several large logging projects—similar to what is being proposed on Pine Mountain—over the past decade. Large swaths of the fire area also burned in 2013 and 2014.

Original Article:

Despite the commonly referenced “year-round fire season,” most fires—especially those that burn the largest areas—occur between May and November. Around 1.7 million acres across the state have burned so far this year, but 96% of this total acreage burned in August alone. In fact, nearly two-thirds of the acreage burned in just four fire complexes that were caused by a record-breaking lightning-storm and heatwave in the Bay Area and along the North Coast.

The string of recent wildfires has caused many to wonder why this seems to keep happening year after year. While last year was quite mild (about a quarter-million acres burned), 2020 may be more reminiscent of 2017 and 2018.

So what’s going on? Well, the answer is complicated.

What Happened Historically?

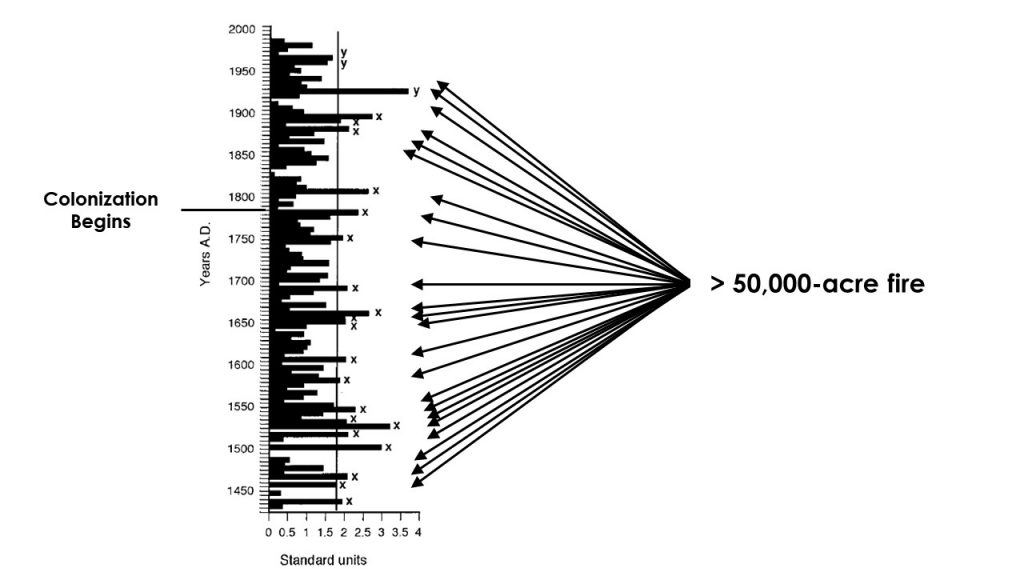

First, it is important to understand that large fires are not a new phenomenon on the California landscape. A group of researchers in 1999 examined charcoal deposits buried in ocean sediments off the Santa Barbara coast and were able to correlate a certain size and abundance of particles to large (> 50,000 acres) fires known to have occurred during the 1900s. They then used this correlation to determine that a large fire occurred somewhere on the local landscape every couple of decades dating back to at least the 1400s. Thus, even before the European invasion and colonization of the region, relatively large fires were not uncommon.

Other researchers have used historical records to determine that possibly the largest fire in California over the last few centuries occurred in the late 1800s. Estimates of the size of the 1889 Santiago Canyon Fire in southern California range from 300,000 – 500,000 acres, which would eclipse recent fires such as the 2017 Thomas Fire and possibly even the 2018 Ranch Fire.

Modern Factors

While large fires have long been part of the California landscape, they may be increasing in their frequency—and this is where it starts to get more complicated. There are numerous reasons why these fires occur in the modern era, but here are likely the most important factors:

- Hotter, drier conditions

- More ignitions

- Invasive grasses and weeds

Climate change is undoubtedly making California hotter and drier. Acute and chronic droughts are likely worsening due to effects on weather patterns and temperatures. There’s evidence that the state is currently in a multi-decade drought that fluctuates periodically. Because of this, vegetation throughout the region may be drier for longer periods of time each year, and dry vegetation facilitates fire spread much more than vegetation with higher moisture content.

If the temperature is high, humidity is low, vegetation is dry, the potential for fire is increased. All that is needed is an ignition. There are over 40 million people living in California. With sprawling suburban and semi-rural areas along the edges of population centers, the number of human-caused ignitions is significant. An overabundance of human-caused ignitions in southern California has led to drastically shortened intervals between fires, which is causing the loss of chaparral in many areas. One of the issues with human-caused ignitions is that they often occur under extreme weather conditions like Santa Ana or Diablo winds. Recently, many large wildfires fueled by hot, dry winds were specifically caused by utility lines or equipment (e.g. Tubbs and Thomas Fires in 2017 and the Camp Fire in 2018). Climate change may also increase the number of lightning strikes in some areas.

While many ecosystems in California have been fire-prone for at least the last two million years, fire regimes and fire risks throughout the state have changed in a relatively short period of time due to the spread of invasive grasses and weeds. This invasion started with the Spanish colonization of coastal California in the late 1700s, and it has only spread and worsened over the centuries since. Only undeveloped areas deep in the mountains have been able to withstand the march of these non-native plants across the landscape. But every new road and ground-disturbing project spreads them farther and farther.

Most invasive grasses are annual plants that do very well in hot, dry conditions—especially in areas where human activity is significant. These plants dry out very early in the year after producing a massive crop of seeds, and due to their structure, they are easily ignitable. Most fires in southern and central California likely start in dry, invasive grass before spreading into adjacent native ecosystems. In fact, most fires start close to a road, where non-native plants tend to thrive. And because these invasive plants are so dry and tightly packed for most of the year, they can spread fire very quickly across vast distances. Their presence can change fire regimes, causing a feedback loop that is difficult to break.

All of these conditions have come together in 2020 to create a situation that would inevitably include large wildfires. Most of northern California has been locked in a serious drought since last year, and the combination of an intense heatwave and lightning storm in August allowed for many ignitions to quickly grow. Perhaps the only thing that separates this year from 2017 or 2018 is the fact that many of the ignitions this year have been natural rather than human-caused. And as this is published, a new heatwave is forecast for much of the state, which will likely result in new fires.

Breaking Down Misconceptions

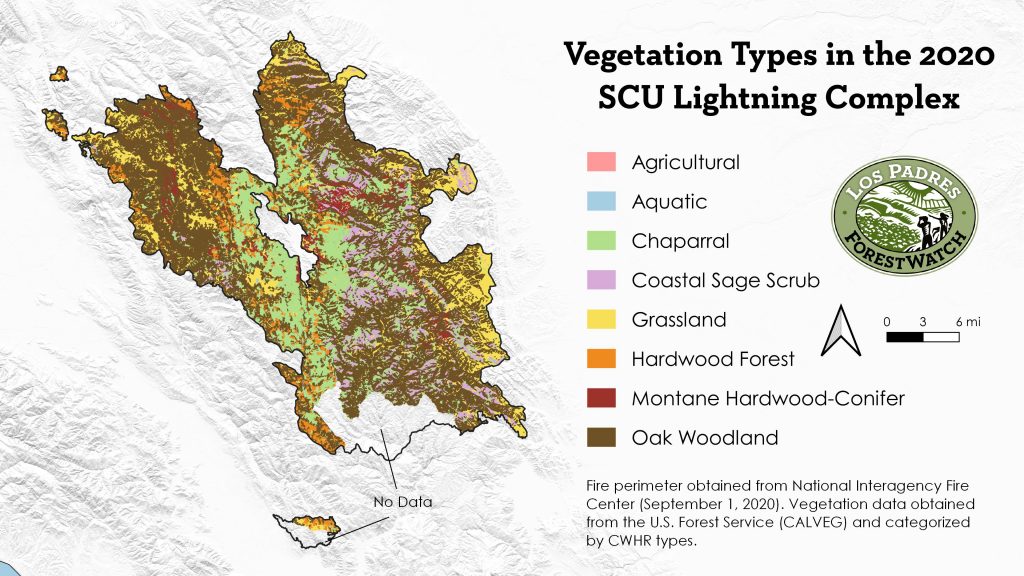

Many media articles and statements by policymakers or agencies have made it seem like these fires are burning vast swaths of conifer forests that have been unmanaged and fire-suppressed for a century. Yet, this is quite far from the truth on the ground. An analysis of all fires so far this year has revealed that of the 1.7 million acres burned, a little less than 32% has been in forest habitats (much of which are hardwood types). Most of the burned acreage has been in chaparral, sagebrush, oak woodland/savanna, and grassland. In fact, nearly 50% of the total burned acreage has occurred in habitats that do not even have a major tree component.

Moreover, many of this year’s fires have burned through areas that burned very recently. Nearly one quarter of the area burned by the state’s second-largest individual fire burned less than two years ago, and 40% has burned within the last five years. The state’s largest fire has burned through large expanses of chaparral that burned in the 2007 Lick Fire—an interval that is too short for many chaparral species to effectively repopulate. In the Los Padres National Forest, the arson-caused Dolan Fire along the Big Sur coast is burning nearly exclusively in areas that last burned in 1999 or 2008, and the fire may soon spread into the mountains that burned in the 2016 Soberanes Fire. Because so much of this area is chaparral—which needs decades between fires—there is concern about conversion to non-native grassland.

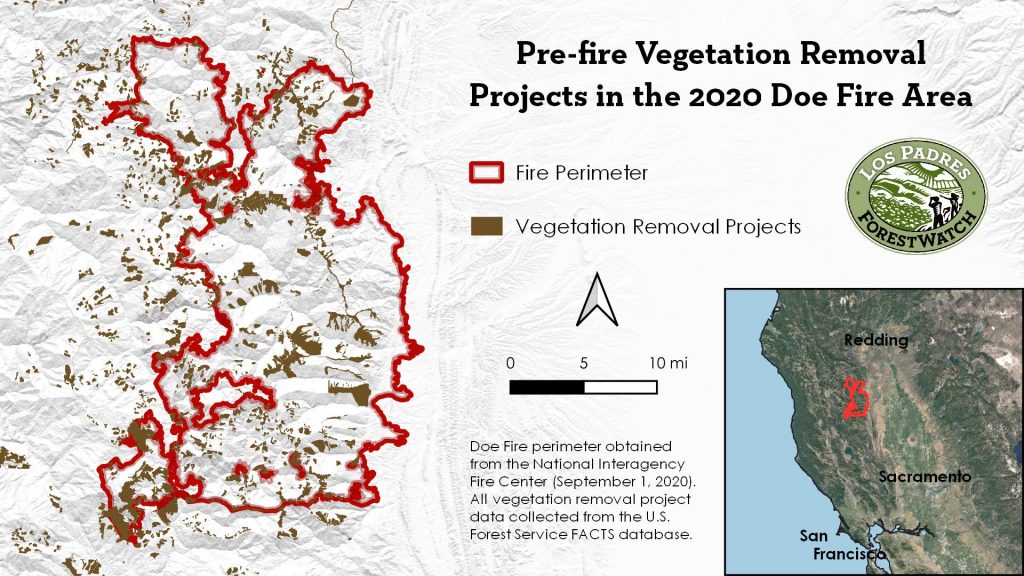

Even one of the few coniferous forest fires has burned through numerous heavily managed areas. Much of the area burned by the lightning-caused Doe Fire in the Mendocino National Forest has been logged, burned with prescribed fire, or had other vegetation removal projects similar to what has been proposed on Pine Mountain Ridge in the Los Padres National Forest. It is far from an unmanaged landscape, yet the fire has still burned over 260,000 acres due to high heat, low humidity, terrain, and wind. And while agencies often tout that these projects reduce future fire severity, several studies have shown them to be ineffective under weather conditions like we have seen this summer. There is even evidence that such projects can worsen fire severity under some conditions, with the largest study of fire severity in the western U.S. showing that fires tend to burn the least severely in forests with the most protections from harmful vegetation removal projects.

Importantly, there is a difference between how fires naturally burn in ecosystems around the state. In chaparral, it is entirely normal for all aboveground vegetation to be mostly consumed during a fire, with just skeletons of shrubs remaining afterward. In many forest types, mixed-severity fire is the norm. This means that the number of trees killed across the entire fire area is highly variable and patchy, which creates incredibly diverse post-fire landscapes. Far from being destroyed, most ecosystems are highly resilient and can even thrive with periodic high severity fire. In fact, patches of forest that burn at high severity (> 75% of trees killed) are biodiverse and important for many wildlife species.

However, it is often believed that modern forest fires are burning at mostly high severity, which has led to increased calls for vegetation removal projects on both federal and state lands. Yet, according to the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity program coordinated by the U.S. Forest Service and several other agencies, even the largest fires in California forests still burn mostly at low to moderate severity. For example, only 10% of the 2018 Camp Fire area and about 20% of the 2013 Rim Fire area near Yosemite burned at high severity. And the largest individual fire in modern California history, the 2018 Ranch Fire? Only about 16% of it burned at high severity.

What Can We Do?

All of these complicated issues actually boil down to a fairly simple concept: we cannot prevent large fires, but we can prevent community destruction.

Most of the focus on wildfire mitigation has been on increasing the pace and scale of vegetation removal projects. These are usually billed as restoration or hazardous fuel reduction, but they often amount to some form of logging trees and clearing chaparral—all of which can exacerbate invasive plant spread and cause serious ecological damage. An example of such a project is the U.S. Forest Service’s proposal to log trees and clear chaparral on Pine Mountain in Ventura County, which has been widely opposed.

The use of prescribed fire in forests is nearly always preceded by logging, and it may be inappropriate for most forest types that naturally experience mixed-severity fire. Prescribed fire in chaparral is another form of adding more fire to an ecosystem that is generally experiencing overly frequent fire as it is.

Yet, policymakers continue to divert money to these lofty projects. The California State Legislature recently attempted to pass a massive bill that would have directed up to $3 billion to vegetation removal projects across the state, but the ill-advised plan was ultimately scuttled just before the legislative session ended.

Rather than pouring hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars into vegetation removal away from homes, large investments should be made into the following:

- Home hardening programs that help homeowners retrofit their structures with fire-safe materials like dual-pane windows, ember-proof vent screens, and fire-resistant roofs.

- Community shelters that can protect people not only from fire but also smoke and heatwaves.

- Defensible space education and workforces that help homeowners wisely manage vegetation within 100 feet of structures, where science has consistently found vegetation management to be the most effective.

- Programs that reduce the amount of development that occurs in fire-prone or dangerous locations (such as box canyons where evacuation is difficult).

- Human-caused ignition prevention, with a focus on roadside ignitions and utility line equipment ignitions.

These investments have been proven to save lives and property. Every dollar spent logging forests or clearing chaparral in the backcountry is a dollar that could have gone instead to helping communities directly. Of course, much more is also needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion. Otherwise, climate change will continue to worsen the conditions most conducive to large wildfires.

The presence of invasive plants, tens of millions of people and homes, and climate change has made the California landscape quite different than it was hundreds or thousands of years ago. While we can look to the past to better understand how our native ecosystems evolved and functioned historically or prehistorically, we must acknowledge that conditions are now different. Future solutions must be focused on what can be changed that will effectively protect communities. Vegetation removal from the landscape has not stemmed wildfires or the loss of lives and property over the last several decades. It may have only made things worse.

We can learn from our resilient native ecosystems about how to co-exist with fire, but it will require us to abandon the notion that we are in total control of the landscape.

For more about wildfire science, click here.

Comments are closed.