For the first time in more than a century, a gray wolf has returned to California’s central coast region as part of an epic journey from Oregon spanning more than 600 miles and eighteen counties in California. The wolf, known as OR-93, is fitted with a radio collar, and was detected in both Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties.

If the wolf continues its westward trajectory, there’s a good chance it will find itself among the foothills of the Santa Lucia Range and could eventually enter the Los Padres National Forest. Wolves occurred historically throughout the region but were hunted to extinction by the early 1900s.

OR-93 was born two years ago southeast of Mt. Hood as part of the White River Pack. He was fitted with a tracking collar by federal biologists and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. Like many young wolves, he then left his pack in search of a new territory and/or a mate, arriving in Modoc County, California in late January.

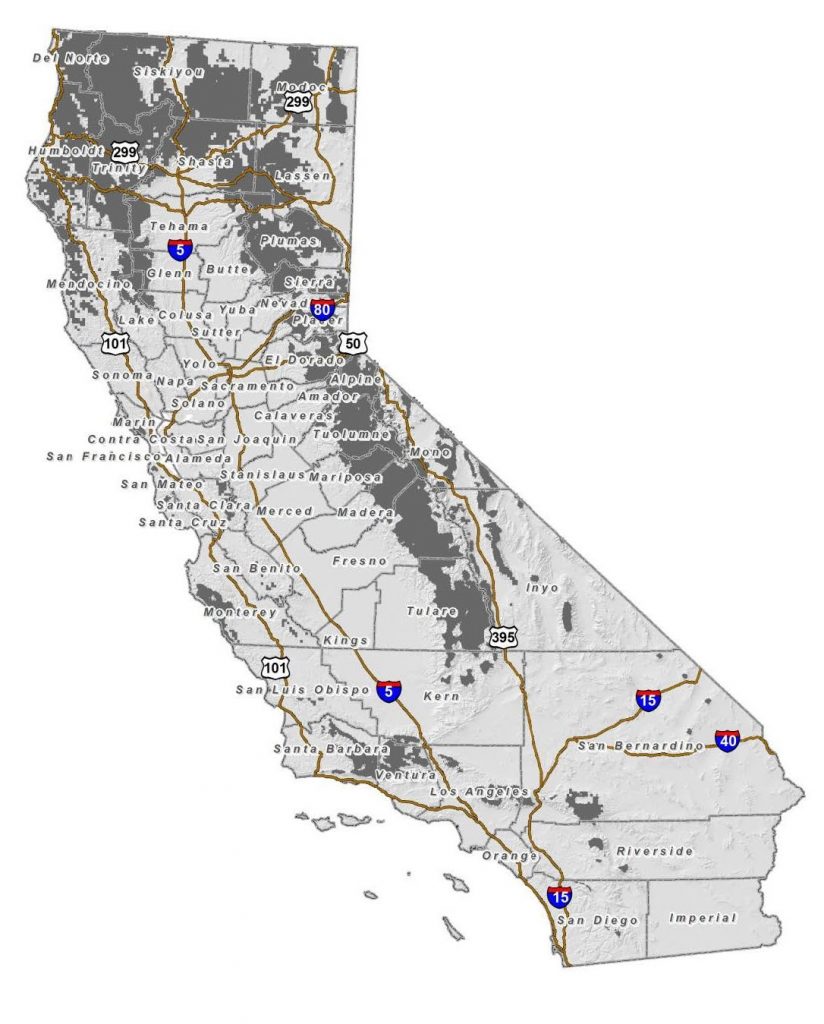

His journey then continued southward through Lassen, Plumas, Sierra, Nevada, Placer, El Dorado, Amador, Calavaras, Mono, Tuloumne, Mariposa, Merced, and Madera counties. In late March, collar readings showed OR-93 in agricultural areas in central Fresno County at the base of the Sierra Nevada foothills. After crossing the busy Interstate 5, subsequent collar readings showed him traveling through San Benito County, and wildlife officials announced on April 1 that the wolf had entered Monterey County, and on April 6 OR-93 had continued south into Monterey County.

Gray wolves are formally protected as endangered under California law, making it illegal to harass, harm, shoot, capture, or kill them. Violations are thoroughly investigated and subject to serious penalties including imprisonment. OR-93 has a purple collar which should make the animal more identifiable. Wolf sightings can be reported to the California Department of Fish & Wildlife. Gray wolves pose very little safety risk to humans, and there are several steps landowners can take to reduce the risk of livestock loss.

Wolves in California Today

Fewer than a dozen known wolves now live in California, including the Lassen pack, which consists of five confirmed wolves; a new pair spotted in Siskiyou County late last year; and OR-93. The seven-member Shasta pack, the state’s first in nearly 100 years, disappeared from Siskiyou County within months after its discovery in 2015 amidst fears of poaching.

California’s wolves were exterminated in the early 1900s by a nationwide eradication program on behalf of the livestock industry. Wolves began to return to Oregon and Washington in the 2000s, and in 2011 a wolf from Oregon (OR-7) made his way into California. OR-93 is the seventeenth wolf known to have entered California in recent years.

Wolves in the Los Padres National Forest?

OR-93’s journey to our neck of the woods suggests that wolves were historically present throughout a significant portion of California’s central coast region and adds to a significant body of anecdotal evidence of wolves in central and southern California.

Wolves were reported in historical accounts in San Bernardino and Los Angeles Counties, and in the coastal range from San Diego to San Francisco. Locally, a forest ranger reported a wolf in 1910 in the Upper Santa Ynez watershed and at a large lemon ranch in Montecito near Santa Barbara. While these accounts cannot be scientifically confirmed, they do suggest that wolves were indeed present in the region.

A wolf was trapped in the mountains of the Mojave Desert in eastern San Bernardino County in 1924, and recent genetic analysis of this museum specimen suggests that it may be a Mexican gray wolf, a subspecies of gray wolf.

Indigenous culture and language can also tell us about the presence of wolves and human relationships with them. A linguistics study by anthropologists at Sonoma State University in 2013 suggests that wolves were a part of tribal culture throughout the state because different terms were used to refer to wolves, coyotes, and dogs. For example, the Chumash word for wolf is miy; for coyote is XoXau (Santa Ynez) and alaxüwül (Ventura); and for dog is hutcu (Santa Ynez), tsun (Santa Barbara), or e-töniwa (Ventura). Similarly, the Salinan tribe in what is now Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties referred to wolves as t’oʹxo (Antoniaño ) or to xoʹ ‘(Migueleño); to coyotes as Lk’aʹ (Antoniaño) or hel’kaʹ (Migueleño); and to dogs as Xutc (Antoniaño) or xutca ‘i (Migueleño).

Suitable Habitat in the Los Padres

For now, scientists can use models to identify areas with suitable habitat for wolves. The California Department of Fish & Wildlife in 2016 evaluated and identified suitable wolf habitat throughout northern California, the Sierra Nevada, and isolated pockets along the coastal mountains in Monterey, Santa Barbara, Ventura, San Bernardino, and Riverside counties. Most of the suitable wolf habitat along the coast is located in—yep, you guessed it—the Los Padres National Forest.

We don’t know if OR-93’s journey will take him into the Los Padres National Forest, nor how long he may stick around. But his presence in our region gives us hope that this won’t be the last time we see—or hear—wolves in California’s central coast region.

Comments are closed.