Adenostoma fasciculatum

The most common shrub west of the Sierra Nevada, chamise is the backbone of the chaparral—a shrubland ecosystem that dominates much of the central and south coasts. While it may be ubiquitous in the Los Padres National Forest and elsewhere throughout the state, there’s a lot that makes this plant unique.

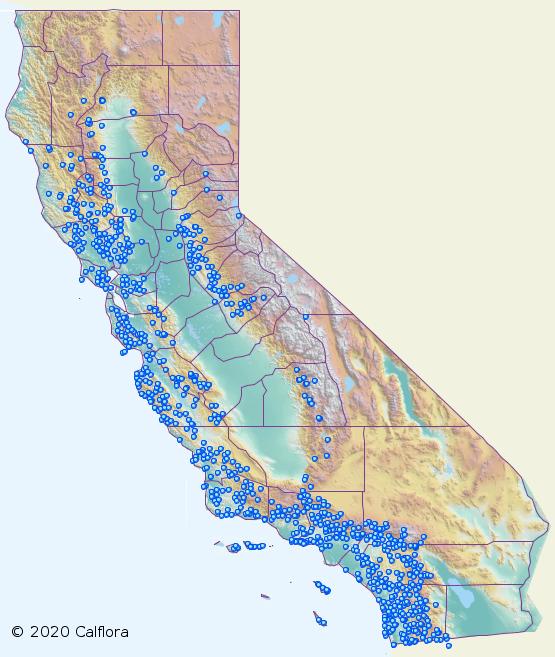

Distribution

Chamise is the most widely-dispersed chaparral species in California. It grows in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada and throughout the Coast, Transverse, and Peninsular Ranges. It is only found outside of California along the Baja Peninsula in Mexico.

In the coastal mountains, chamise is often one of the dominant shrubs in chaparral. In fact ‘chamise chaparral’ is one of the many types of this unique ecosystem and is characterized by abundant chamise and only a few other species. The plant is also commonly found in other types of chaparral that either have a mix of different shrub species or are dominated by other shrubs such as ceanothus.

In the Los Padres National Forest, chamise is found in every mountain range except for the San Emigdios north of Mt. Pinos. The species is often found on more south-facing slopes in the region. Excellent places to see large stands of chamise are on the south slopes of Pine Mountain in Ventura County and throughout much of the Santa Ynez Mountains near Santa Barbara. Chamise is also a major component of the chaparral found in the Big Sur region.

Description

Chamise is a fascinating shrub that looks different depending on how close you get to it and what time of year you see it in. From a distance, you might notice the evergreen plant along with other shrubs in the chaparral forming a dense stand that would be difficult to walk through. It grows up to 13 feet tall, and you will rarely find a chamise by itself. Upon closer inspection, the most striking thing about the plant is its leaves—when it isn’t blooming, of course.

The leaves are very small, only a few millimeters in length. They are clustered similar to California buckwheat or even many pines, with the small leaf bundles referred to as fascicles (which gives rise to the species name, fasciculatum). Each leaf is also thick and typically point toward the sun. These traits help the plant conserve water and reduce the amount of drying the experience from direct sunlight. In fact, just about every characteristic of the leaves allows the plant to better survive the dry conditions of our region.

During the spring, chamise puts on a spectacular wildflower display. Its blossoms are dense clusters of tiny white flowers that cover the ends of its stems. These flowers quickly dry out and turn a beautiful reddish-orange color while staying on the plant throughout the fall. This color change often gives entire stands of chaparral a deeply autumnal look later in the year.

Relationship With Fire

Like most chaparral species, chamise is well-adapted to the region’s natural fire regime. During these naturally large and intense blazes, most of the plant’s aboveground biomass burns—though its largest stems are left blackened and standing.

However, this usually does not kill the plant. Within weeks of a fire, tiny stems and leaves emerge immediately around the charred base of the plant. These grow from an enlarged, partially buried mass called a burl that contains growing buds protected from the flames. This resprouting ability allows chamise to regrow relatively quickly in the years after a fire.

Chamise also has unique seeds that sit dormant in the soil for decades until being stimulated primarily by chemicals in smoke from the fire. Thus, chamise is able to also repopulate an area with seedlings, many of which survive and become mature plants that will be able to resprout after the next fire.

However, this and other chaparral species can be threatened by fire that occur too soon after the previous fire. Chamise needs time to replenish the carbohydrates stored in its root system that enable it to resprout after a fire. It also needs time to replenish its seedbank in the soil. Fires naturally occurred every 30 – 150 years before human-caused ignitions drastically altered this pattern, mostly during the last century. You can learn more about fire in our region here.