Pelecanus occidentalis californicus

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

- Delisted – Endangered Species Act (2009)

- Least Concern – IUCN Red List

California brown pelicans are a subspecies of brown pelicans, the smallest of the seven pelican species worldwide. They measure about 4 feet in length and have a wingspan of just over 6.5 feet. They weight about 8 pounds, with the males slightly larger than the females. They have long wings, a heavy body, a huge bill, and a very distinctive pouch for the capture of prey. The webbing between their toes makes them strong swimmers capable of plunging into the water and swimming after their prey.

Habitat

California brown pelicans are aquatic birds that love the beach. They are typically found on rocky or vegetated offshore islands, in harbors and marinas, in estuaries, and in shallow breakwaters and sheltered bays. They are sometimes seen out at sea searching for food. Because their preferred nesting locations are on islands, the only breeding colonies of California brown pelicans are located within the Channel Islands National Park on Anacapa and Santa Barbara Islands. They prefer islands because of the lack of predators and human inhabitants.

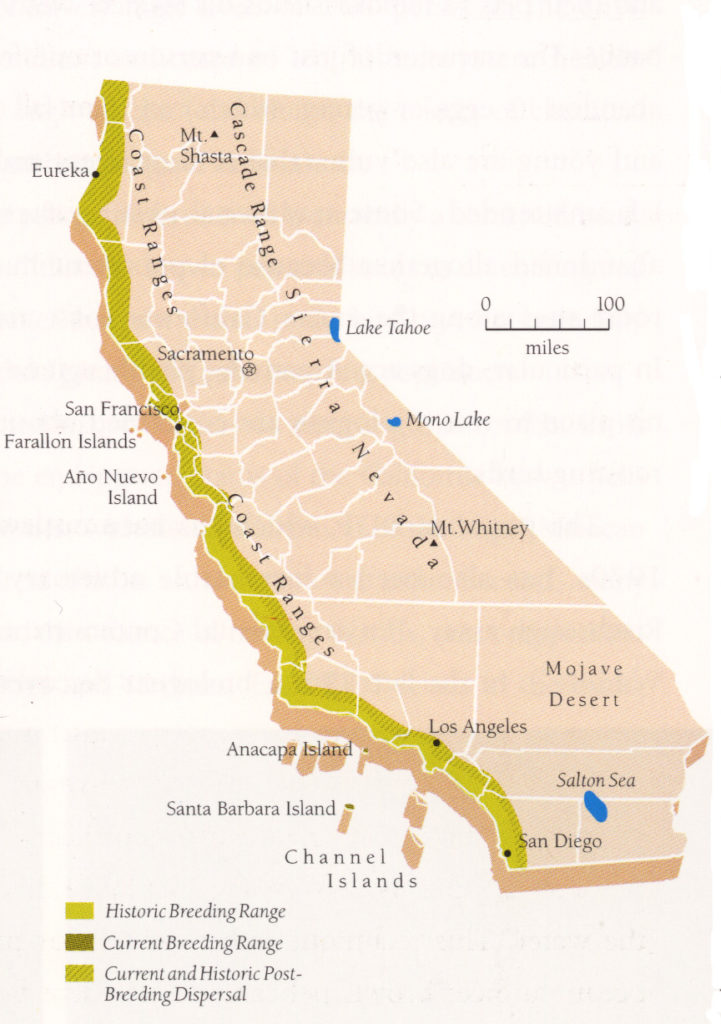

Distribution and Migration

The California brown pelican’s range extends from British Columbia, Canada to Nayarit, Mexico. While their breeding range is between the Channel Islands and Central Mexico, about 90% of the Californian brown pelican population nests in Mexico. The only breeding colonies of Californian brown pelicans on the west coast of the United States are on the Channel Islands—which also provide great roosting habitats.

Major roosting areas occur on Santa Cruz and Anacapa Islands. As summer approaches and the breeding season comes to an end, flocks migrate north to various parts of Canada. In the autumn, brown pelicans begin their descent south to breeding areas in Mexico in anticipation of the coldest months of the year.

California brown pelicans can be found roosting and foraging along the few miles of coastline encompassed by the Los Padres National Forest in the Big Sur area, particularly during the summer months.

Mating and Nesting

Breeding season begins when the male pelican chooses a nesting site and begins to court a potential mate with an aerial dance. Once a female reciprocates his interest, they begin to build a nest together. The male scouts for sticks and brings them to the nest site where the female does most of the construction. On Santa Barbara and Anacapa Islands, brown pelicans typically nest on inaccessible slopes, canyons, and high bluff tops and edges. They can also nest on the ground, in native shrubs, and occasionally in trees.

Nesting season typically begins in March and extends through late summer. A normal clutch size is three eggs and males and females typically share incubation duties. Breeding success is highly dependent on their main supply of food: northern anchovies and Pacific sardines. Nest abandonment can even occur if this supply of food rapidly declines. In the first 3-4 weeks after hatching, chicks are featherless, blind, and completely dependent on parental care. Both the male and female pelicans feed their chicks until they fledge at around 13 weeks of age. Parents take turns leaving the nest to catch fish, store it in their throat pouches, and regurgitate it to their chicks.

Feeding Behavior

The California brown pelican hunts for food within five miles of land, although some may travel as far as forty miles away from shore in pursuit of their prey. It is a unique feeder because it is the only pelican that can plunge-dive for its food. Some are even able to dive from as high as 70 feet! After spotting their prey and initiating their dive, pelicans hit the water with such a high force that it stuns their prey and gives them time to scoop it up with their bills. Air sacs throughout the body help them manage the shock from the collision. Capable of carrying three gallons of fish and water, it has the largest pouch of any bird in the world.

Pelicans can eat up to four pounds of fish per day. Their diet consists of menhaden, smelt, anchovies, mackerel, sardines, and some crustaceans. During the mating season in California, most of the pelican diet consists of the northern anchovy. Pelicans also feed by sitting on the surface of the water and scavenging for food. This is most effective when dense schools of fish are nearby and the water is too muddy to see. Pelicans also acquire food by approaching fishermen for handouts, stealing food from other seabirds, and scavenging dead animals.

Conservation and Future Threats

The brown pelican has a woeful history. At the beginning of the 20th century, pelicans were hunted and killed to decorate hats and jackets. Many were shot by fishermen who accused them of reducing their fish supply. Hope for these birds came in the form of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918 which made it illegal to kill migratory birds. However, in the late-1900s, a pesticide called DDT used to control mosquitoes caused pelican eggshells to be very thing, increasing chick mortality and wiping out entire populations of these birds. In 1970 on West Anacapa Island, 552 nesting attempts were made and only one chick survived. This nearly drove brown pelicans to extinction.

In 1970, the brown pelican was listed as an endangered species and in 1972, the United States EPA banned the use of DDT. Between 1985-2006, the Anacapa colony produced an average of 770 nests per year. Pelican populations began to recover and the brown pelicans were taken off the endangered species list in 2009.

However, since 2009, thousands of California brown pelicans have experienced nesting failures and starvation because of overfishing of Pacific sardines—a primary food source for brown pelicans.

In addition to population decline driven by food scarcity, California brown pelicans face a multitude of other threats. When pelicans scavenge on offal discarded by fishermen, they get covered with fish oil which breaks down their feather barbules and prevents them from interlocking, leading to hypothermia. At the International Bird Rescue’s San Francisco Bay Center, researchers commonly admit pelicans that have been injured by fishing lines and hooks.

Oil spills from offshore drilling reduce the waterproofing capacity of their feathers, causing pelicans to drown. Plastic garbage is also a major threat. Birds often mistake plastic pieces for food and die of starvation when their stomachs become filled with garbage.

ForestWatch is working to ensure that California brown pelicans continue to have prime roosting and foraging habitat in the coastal areas of the Los Padres National Forest by monitoring activities that could potentially impact this habitat or the birds themselves.