Buteo swainsoni

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

- Threatened – California Endangered Species Act (1983)

Swainson’s hawks are relatively small for buteos, a group of hawk species that are typically large, broad-winged, and short-tailed. They’re a little larger than a Cooper’s hawk and a bit smaller than a ferruginous hawk. These social birds of prey are usually seen in soaring groups or in and around grassland areas, but you may have trouble spotting them in California, where they’ve largely disappeared.

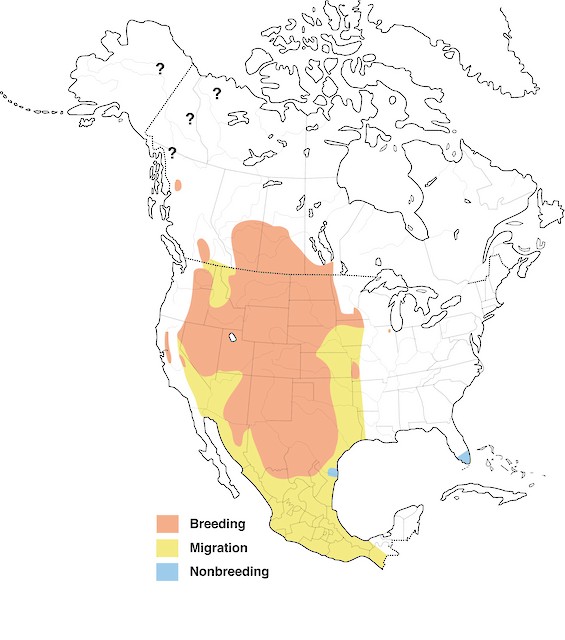

Range and Migration

Swainson’s hawks are a rare sight to see. In California, Swainson’s hawks have historically lived on the Modoc Plateau, in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys, along the southern coast, and at scattered sites in the Colorado and Mojave deserts. Today, the number of breeding birds has greatly reduced in many of these sites and the species has completely disappeared in coastal southern California. Since 1991, the Central Valley is the only region in California that still supports a small population of regularly wintering birds.

These birds have been observed flying through the Los Padres National Forest, and a nesting pair was observed in 1981 in eastern San Luis Obispo County. Portions of the Los Padres National Forest contain suitable habitat for Swainson’s hawks, and the species may be able to utilize these areas if it recovers and expands its current range.

Swainson’s hawks are long distance migrants, traveling a roundtrip of as much as 12,000 miles from North America to South America and back. As summer comes to an end, Swainson’s hawks prepare for one of the longest migrations of any American raptor. They flock up by the thousands, mixing with turkey vultures, broad-winged hawks, and Mississippi kites to create a large flowing mass of birds. Each bird prepares to ascend by waiting for the air to warm and then soaring on the rising air current with its wings spread wide. At the top of the thermal column, the hawk folds its feathers and tail back, beginning the slow descent in search for another gust of warm air. These groups of migrating birds, or “kettles,” are a spectacle to behold, making them a much awaited view in the fall when they go south and then again in the spring when they come back north.

Reproduction

Swainson’s hawks are long-lived, with the oldest known hawk living to be more than 26 years old! They are monogamous birds and they generally take on gender roles in the pursuit of raising their young. These love birds will perform a “sky dance” together above the nesting site. To impress the female, a male hawk will make a steep dive and recover up to rejoin the female. If the female is impressed by this display of courtship, they will begin creating their nest—generally in trees such as cottonwood, willows, sycamores, valley oaks, and walnut. Male hawks generally choose the nesting site, usually near the top of the tree. The male brings most of the materials to create the nest, including sticks, twigs, weeds, and debris items. Working as a pair, they spend the next 2 weeks constructing the nest and lining it with grass, hay, weed stalks, bark, and even cow dung.

After the female lays the eggs, she will perform most of the incubation while the male hunts for food. Occasionally, she will be relieved for brief periods so she can hunt and stretch. The incubation period lasts roughly 35 days before the chicks are born. Swainson’s hawks are aggressive around the nest site during the breeding season. The pair will often chase off predators such as coyotes, golden eagles, and bobcats and dislodge other raptors to protect their young. The young chicks learn to fly about 40 days after hatching and they will remain with their parents until fall migration.

Feeding

Swainson’s hawks are extremely skilled carnivores. They’re able to forage on foot or scan the ground for prey from above. During breeding season in the spring, Swainson’s hawks generally hunt for rodents, rabbits, and reptiles to feed their young. In other seasons when they’re not breeding, adults feed mostly on insects—particularly grasshoppers, caterpillars and dragonflies. These hawks have excellent vision that gives them the ability to catch flying insects mid-flight.

Threats

The largest threats that face Swainson’s hawks in California are loss of nesting sites in riparian forests, loss of foraging habitat due to development, and high mortality due to pesticide use along the migration route. Even small losses of habitat can result in permanent losses of Swainson’s hawks in the region.

Additionally, records from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife show that as many as 40 Swainson’s hawks have been killed from eating insects that have been sprayed with organophosphate and carbamate insecticides in agricultural fields. In the pampas of Argentina where the birds spend the winter, approximately 5,000 dead hawks have been found poisoned by organophosphate insecticides and dimethoate—which are used to control grasshopper outbreaks. Thankfully, education programs for farmers and restrictions on the use of these highly toxic insecticides have reduced the impacts of these compounds on wintering Swainson’s hawks.

In California, population trends of Swainson’s hawks are difficult to describe due to insufficient data. They are currently absent from much of their historic range. Large numbers of Swainson’s hawks still occupy the Central Valley, with an estimated of 420-1,000 pairs. However, annual losses of riparian habitats due to residential development threaten their continued existence. Nevertheless, hope to restore these magnificent creatures remains as reports of recolonization of historic habitats in Los Angeles and Owen’s Valley suggest that their populations respond well to the restoration of habitat conditions.

Conservation

Because Swainson’s hawk population size, density per unit of suitable habitat, and survival rates are not well known outside of a few small study areas, establishing population objectives in California will be rather difficult. Furthermore, we cannot control how this species may be affected by unfavorable conditions outside of California along its migration path.

Because over 95% of known nest sites in the Central Valley of California are on private lands, management of Swainson’s hawk habitats is strongly influenced by changes in land ownership. Availability of nesting trees and suitable foraging habitat for these birds must be protected on these lands if we don’t want to see declines in their population. Landowners in the Central Valley should be encouraged with state incentives and local planning efforts to maintain a diverse agricultural community that leaves room for nesting and foraging sites.