Goleta, Calif. – Yesterday, the Forest Service announced its approval of the second of two commercial logging projects in the Los Padres National Forest. The approval of the 1,600-acre project along Tecuya Ridge comes just five months after the agency authorized an adjacent 1,200-acre project allowing commercial logging in Cuddy Valley at the base of Mt. Pinos.

The agency fast-tracked both projects without preparing a standard environmental assessment or environmental impact statement, instead declaring that the projects were excluded from environmental review under a loophole in the National Environmental Policy Act. A full environmental review examines potential impacts to plants and wildlife as well as alternatives to the proposed activities. The normal review process also provides more transparency and opportunities for the public to weigh in with concerns about the project.

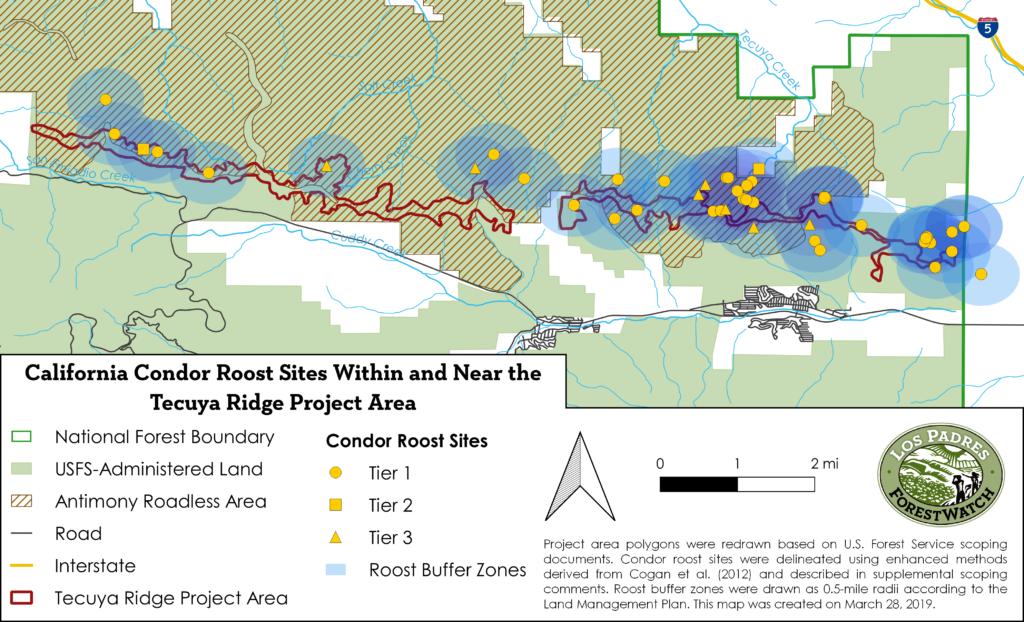

The logging area provides prime habitat for endangered California condors. According to condor tracking data provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, nearly fifty condor roost sites occur within a half-mile of where trees will be cut and removed. These roost sites are typically large dead or live trees that are used by condors for resting overnight between long flights. Federal standards require a minimum half-mile buffer from condor roosting sites to protect them from disturbance, given their sensitivity and importance in condor survival.

“There is simply no place for commercial logging in condor country,” said Los Padres ForestWatch Conservation Director Bryant Baker. “With approval of this project, the Forest Service is setting a dangerous precedent for shirking environmental review and public input for logging projects that can have significant impacts on endangered species in the Los Padres National Forest.”

The project would remove trees of all sizes along 12 miles of Tecuya Ridge near the northern border of the Los Padres National Forest and allow for a commercial timber sale to be offered to private logging companies. The decision states that the timber sale would make the project cheaper.

The decision—signed by Forest Supervisor Kevin Elliott—describes operations that would remove large trees using feller bunchers and rubber-tired or track-mounted log skidders and loading them onto logging trucks at cleared areas called landings. Up to 95% of smaller trees and shrubs would be mechanically masticated. The leftover slash would be tractor piled along with post-logging machine piling and pile burning. The agency anticipates that these activities would repeat every 3 to 7 years.

A New Low for Public Participation and Transparency

The two commercial logging projects represent a shift in how the Forest Service authorizes large tree removal projects in the Los Padres National Forest. Since 2006, officials have only approved such projects after rigorously evaluating their environmental impacts in an environmental assessment that is made available for public review and comment prior to approval.

Other projects that were aimed at removing trees in the few mixed-conifer areas in the Los Padres National Forest have generally included a limit on the size of trees that can be removed. For example, a Frazier Mountain thinning project that was approved in 2012 only allowed for removal of trees smaller than 10 inches in diameter, or roughly the size of a basketball. Normally, anything larger than this would be left in place as countless scientific studies have highlighted the importance of retaining large, fire-resistant trees to reduce the risk of high-intensity fire. However, the recently-approved project on Tecuya Ridge as well as Cuddy Valley project would allow a timber company to remove massive, old-growth coniferous trees.

Logging Ineffective Against Wildfire Risk

The Trump Administration is billing the commercial logging project as a fire protection measure. However, countless studies have shown that logging is an ineffective or even counterproductive measure for reducing wildfire risk. Similar to many fires before it, last year’s tragic Camp Fire burned intensely and quickly through a large logged area in the Plumas National Forest and across private lands that had been subject to timber harvesting before it devastated the town of Paradise.

“The science is telling us that commercial logging projects like these not only damage critical wildlife habitat, they also usually make wildland fires spread faster and burn hotter,” said Dr. Chad Hanson, a forest ecologist with the John Muir Project. “The Forest Service’s logging proposals will increase threats to local communities from wildland fire,” he added.

Scientists have long-stated that the most effective vegetation management should take place directly around the home and immediately adjacent to communities. The Forest Service followed this model in planning two such projects in 2007 to establish defensible space directly adjacent to homes abutting national forest land and construct two fuel breaks directly adjacent to Frazier Park and Lake of the Woods. ForestWatch formally supported both projects. However, more than ten years later, the Forest Service has still not completed the approved fuel break work.

Research has also repeatedly shown that community-focused measures are more successful and cost-effective than landscape-level vegetation treatment. These measures include retrofitting existing structures with fire-safe materials, improving early warning and evacuation systems, creating fireproof community shelters, and curbing development in fire-prone areas.

Public Opposition Ignored

The Forest Service received over 1,000 public comments before the decision—approximately 99% were in opposition to the commercial logging proposal. ForestWatch submitted technical and legal comments highlighting several issues with both projects in partnership with the John Muir Project of Earth Island Institute and the Center for Biological Diversity, and another letter requesting that the projects undergo standard environmental review joined by the California Wilderness Coalition, Kern Audubon, Sequoia ForestKeeper, Kern-Kaweah Chapter of the Sierra Club, TriCounty Watchdogs, and Earth Skills. Since the Forest Service excluded these projects from environmental review, there is no formal appeals process, leaving litigation as the only option for the public to seek changes to the project. ForestWatch and its partners at the John Muir Project and Center for Biological Diversity are currently evaluating the best course of action to take to avoid impacts to the area and to endangered California condors.

Comments are closed.