The tale of the California grizzly bear (Ursus arctos californicus) is a familiar one. It is the tale of a misunderstood animal and the people who marched it off the cliff of extinction. While utterly depressing, there is still much we can learn from the rise and fall of the California grizzly—and by examining what once was and could have been, perhaps we can better co-exist with the wildlife still roaming the California landscape today.

This is the first in a three-part series about the last grizzlies in California, including in what is now the Los Padres National Forest. In this entry, you will learn some of the basics about California grizzlies based on the now decades-old work of researchers such as Tracy Storer and Lloyd Tevis (who in the 1950s wrote the preeminent book on the species) as well as newer genetic research.

Evolution of the California Grizzly

The California grizzly is considered a former subspecies of the brown bear (Ursus arctos), a species that still has many subspecies occupying much of the northern hemisphere. According to recent genetic studies, the brown bear diverged from the cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) about 1.2 – 1.5 million years ago in Asia. Around 50,000 – 70,000 years ago, brown bears crossed the Bering Land Bridge into what is now Alaska. However, these bears did not make it to the California region until after the end of what is known as the Last Glacial Maximum (i.e. the last time glaciers and ice sheets were at their peak extent across the globe) about 11,000 – 13,000 years ago. Around this same time, the short-nosed bear (Arctodus spp.) that had occupied North America for approximately 1.8 million years went extinct, eliminating competition for the newly arrived brown bears.

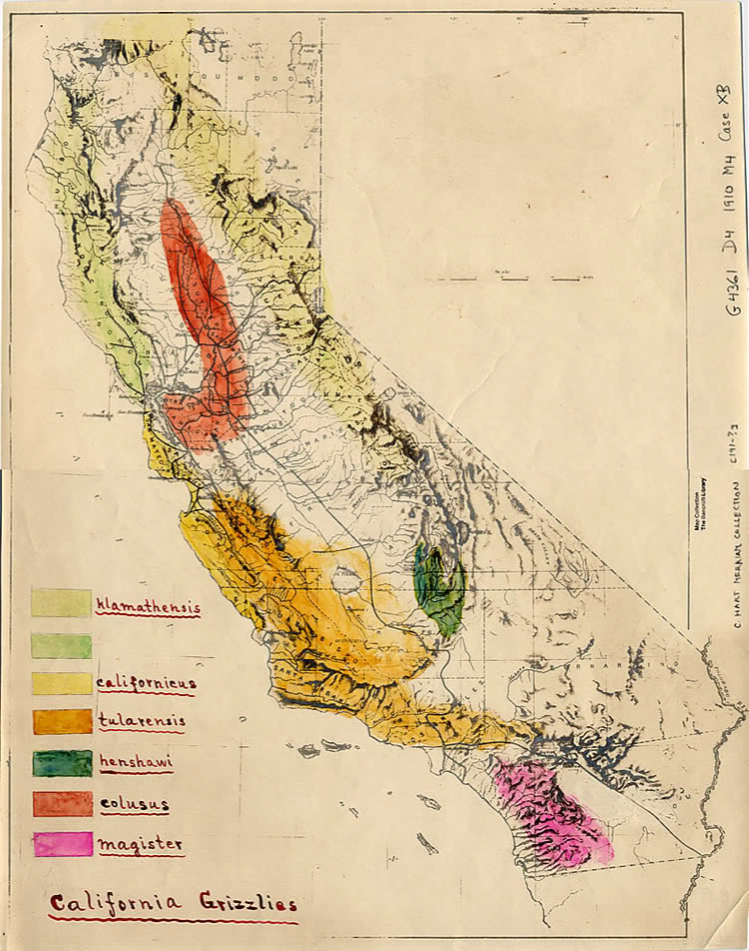

Here is where things get a little muddled. There has been debate over more than a century about the number of subspecies of brown bears in North America. American zoologist C. Hart Merriam—the Chief of the Bureau of Biological Survey (a precursor to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)—became fixated on studying bears in North America in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Merriam eventually described 86 different subspecies of brown bear, including seven in California alone. However, other scientists have since disagreed with his findings, noting that Merriam’s classification included separations based on very minor differences. In their seminal book on the California grizzly published in 1955, Storer and Tevis considered there to be one distinct subspecies in California: Ursus arctos californicus. This name came from a Monterey County specimen that Merriam described, and the researchers believed the name was fitting for the subspecies that once flourished in California.

When exactly the California grizzly began to occupy what is now the Los Padres National Forest is unclear. We do know that bones of a female were found in the La Brea Tar Pits in 1914. Radiocarbon dating of these remains place it in southern California at least 5,000 – 6,000 years ago. Regardless, it is clear that these bears were expanding their range over many thousands of years leading up to the arrival of Europeans and Americans on the landscape.

As an important note, the term “grizzly bear” today generally refers to the subspecies of brown bear still found in the Rocky Mountains of the U.S. and Canada (Ursus arctos horribilis). While all North American brown bears are genetically similar, the California grizzly was considered similar to the Kodiak brown bear that still lives in Alaska (Ursus arctos middendorffi) due to its size. The Kodiak brown bear and California grizzly are considered the largest and second largest brown bear subspecies that have lived North America so far.

The Largest Land Animal in California

Had you lived a century or more ago and seen a full-grown California grizzly in person, undoubtedly the first thing you would have noticed is the enormity of the animal. Early reports indicated that adults could reach up to 10 feet long from nose to tail and 3 – 4 feet tall when standing on all fours. While the grizzlies spent most of their time walking, foraging, and hunting on all four legs, they would stand on their hind legs for various reasons, easily reaching heights of 9 to 10 feet.

The weight of these magnificent creatures appeared to have been often overestimated to the benefit of newspapers publishing tales of encounters in the wild and individuals hunted and brought to town for spectacle and meat sale. The most accurate measurements put the maximum weight of a male California grizzly (like other brown bears, males tended to be larger than females) at 1,200 pounds. The average weight was likely much lower, however. As some researchers noted in the 20th century, grizzlies tend to look larger than they really are, perhaps due to their unique shape and long coats of fur.

As they were by far the largest land animal in California, with strength and defensive measures to boot, they had no natural predators. It was not until Euro-American colonization that these lumbering behemoths unfortunately had something to fear across their range.

A Grizzly (or Grisly?) Appearance

The name “grizzly” can be traced back to Lewis and Clark’s descriptions of bears encountered during their famous expedition. On May 5, 1805 along the Missouri River in what is now McCone County, Montana, Clark wrote in his journal:

The river rising & Current Strong & in the evening we Saw a Brown or Grisley beare on a Sand beech, I went out with one man Geo. Drewyer & Killed the bear, which was verry large and a turrible looking animal, which we found verry hard to kill we Shot ten Balls into him before we killed him, & 5 of those Balls through his lights…

This is the first written record of the use of a term similar to grizzly bear. It is also one of the earliest records of a brown bear being shot and killed by Americans for no apparent reason—one of countless such incidents over the decades to come.

Clark’s use of the word “grisley” has caused some confusion, as it was not immediately clear whether he meant it in the same way as the word grisly (essentially meaning horrifying) or the word grizzly (meaning gray or gray-haired). Other members of the expedition used the term grizzly in their own journals, indicating that the name was indeed referring to the bear’s fur (also known as pelage). Modern grizzlies in the Rockies tend to have grayish fur on much of their bodies. This is especially easy to see when compared to a black bear.

California grizzlies may have had even more variation in color than even the other subspecies of brown bears in North America. In 1918, Merriam described a female from the Santa Ana Mountains as being “dusky or sooty all over except the head and grizzling of back.” The top of the head and the neck of this individual was described as dark brown, and its legs and underside were noted as “wholly blackish.” Descriptions of other California grizzlies varied somewhat, likely depending on the age, sex, and environmental conditions of each bear.

Like other grizzlies, those in California appeared to grow (while their skulls changed in shape) for the first seven or so years of their life. Compared to black bears that have a straight face shape when viewed from the side, the face of the California grizzly and other brown bear subspecies is “dish-shaped.” In this marvelous maw you would have found up to 42 diverse teeth that allowed them to utilize omnivorous diets.

Besides its size, the California grizzly was easily distinguished from the smaller black bear by its large hump between the front shoulders. All brown bears have this telltale hump, which arises from the big muscles that attach to the backbone there. These muscles aid grizzlies in digging, one of their primary foraging activities as they eat substantial amounts of bulbs, roots, and small rodents. Another physical trait of the California grizzly aided in digging as well: massive claws. The claws on the front paws were larger, longer, and less curved compared to those of black bears. Over many years of life, these claws would sometimes wear down due to the immense amount of day to day digging that California grizzlies would do—but more on the feeding habits and behaviors of the California grizzly in part two of this series.

The Grizzly’s Distribution in California

Though skins, pelts, fossils, and other physical remains of the California grizzly are surprisingly sparse today, written records from early Spanish excursions into what is now California to newspapers and books published during the final years of the subspecies are abundant. These records indicate that grizzlies occupied much but not all of the state. Grizzlies were ubiquitous in the Coast, Transverse, and Peninsular Ranges before serious hunting and agricultural and urban expansion began. The bears were also found in the Sierra Nevada and southern Cascades, but there they may have been less common than the smaller black bear due to differences in habitat requirements. Grizzlies were also found in parts of the Central Valley such as the Sacramento Valley. The great deserts of southeastern California were devoid of grizzlies due to the lack of food to sustain them.

Grizzlies were found throughout the Los Padres National Forest both before and after the land was designated as such. Most records come from the Ventura County portion of the Los Padres, especially during the late 1800s and early 1900s, but this may be due in part to the fact that there were humans living there and writing about encounters with local bears.

A Look Ahead to Parts Two and Three

This is it for part one of The Last Grizzlies of the Los Padres. Stay tuned for part two, which will talk more about how the grizzly thrived in the region as well as its early encounters with humans. Part three will then focus on the rapid demise of the California grizzly throughout the state and in the Los Padres National Forest, which served as one of the last bastions for the subspecies into the early 20th century.

Selected References for Further Reading

Wright, W.H. 1909. The Grizzly Bear. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York.

Barlow, A. et al. 2021. Middle Pleistocene genome calibrates a revised evolutionary history of extinct cave bears. Current Biology, 31:1771-1779. doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.073

Miller, C.R., L.P. Waits, and P. Joyce. 2006. Phylogeography and mitochondrial diversity of extirpated brown bear (Ursus arctos) populations in the contiguous United States and Mexico. Molecular Ecology, 15:4477-4485. doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03097.x

The California Grizzly Bear. La Brea Tar Pits & Museum.

Comments are closed.