Just a handful of the approximately 16,000 public comments received last year by the Forest Service supported its proposal to log on Pine Mountain, according to a recent analysis of records obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. The proposal—announced by the Trump administration and currently under review by the Biden administration—would expedite logging and removal of chaparral across six miles of Pine Mountain Ridge, deep in the Ventura County backcountry. After generating more opposition than any single project ever proposed in the Los Padres National Forest, the project decision has been pushed back twice. It is currently expected in September.

ForestWatch’s analysis of the requested documents turned up just five letters in favor of the project—four from individuals and one from a logging industry lobbying group, the American Forest Resource Council.

Similar to the detailed comment letter submitted by ForestWatch and its partner organizations, nearly all public comments disputed the agency’s use of categorical exclusions (CEs)—loopholes that allow the Forest Service to skip environmental studies normally required under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for a project of this size and scope—especially in a sensitive environment important to and visited by so many people.

“The project is part of an alarming trend of commercial logging projects and biomass harvest in the Los Padres National Forest and across the country,” said ForestWatch director of advocacy Rebecca August. “The Trump administration accelerated this trend by pressuring agency officials to use these loopholes and by making it twice as profitable for private companies to log federal timber. People see right through this, and they’re speaking out.”

Two other such projects in the area, also proposed under loopholes, are currently under review by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The announcement of a fourth disturbingly similar proposal in the area atop the Los Padres National Forest’s tallest peak, Mt. Pinos, is expected any day. The Biden administration is conducting a review of several expedited logging projects across the country as well as a litany of gutted regulations intended to protect the environment, drinking water, and public health.

Who Commented?

Included in the comments critical of the project were letters from former Ojai Mayor Johnny Johnston, Ventura County Supervisor Linda Parks and former Supervisor and current State Assemblyman Steve Bennett, State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson, Congressmembers Julia Brownley and Salud Carbajal, leaders from local Native American groups, and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Group letters signed by nearly 100 local businesses and over 70 environmental organizations, as well as eleven professional archaeologists and ethnohistorians, were also submitted.

At least 12 scientists submitted technical comments on environmental, cultural, and recreational resource impacts without compensation. They included foresters, botanists, ecologists, wildlife biologists, and other scientists who have worked locally with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, the Department of the Interior, and the University of California. Several note decades of experience with California condors, spotted owls, NEPA analysis, and wildfire, as well as service as firefighters with the US Forest Service. All the scientists stated that the project and the use of CEs cannot be justified as written.

Impacts to Chumash Resources

Pine Mountain ridge has “extraordinary cultural significance as part of the sacred complex of sacred lands in the Chumash upper world,” said Julie Tumamait-Stenslie, chair of the Barbareño/Ventureño Band of Mission Indians. She says their primary concern about the project is “a lack of attention and near total insensitivity to the potential impact to Chumash cultural values and resources.”

She notes that the project does not require foresters to notify tribal leaders about the discovery of cultural resources until after the project has started and heavy equipment is already in the field, with no Chumash monitors on site and no plan to protect those resources or mitigate damage before it takes place. The proposal, she says, violates state and federal standards for cultural protections and calls for an environmental impact statement that includes the consideration of a “no project” option.

The Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation said that the proposal is in violation of laws protecting Native American autonomy over their lands and resources as well as religious freedom. “We also acknowledge that our non-Native allies frequent the site for recreation and their own type of spiritual refreshment. We stand in solidarity with them against this project.”

Wishtoyo Chumash Foundation, a Native-led California nonprofit environmental and cultural organization, also opposes the project, citing potential negative impacts to natural cultural resources vital to Chumash Peoples, sites of cultural importance, damage to old growth chaparral and mixed coniferous forest, harm to sensitive and endangered species, and conservation of inventoried roadless areas and proposed wilderness among its concerns.

A group of eleven professional archaeologists and ethnohistorians authored a letter also insisting on a full environmental review that states, “we believe that the project is flawed as it does not consider any cultural, religious, or spiritual significance the area might have to Chumash stakeholders and/or their respective relationships to the land.”

The letter identifies Pine Mountain ridge and Reyes Peak as one of the three sacred peaks with Mount Pinos and Frazier Mt., as well as an ancient trail system that crosses directly through the project area connecting coastal villages to the Cuyama River and interior villages. Federal law requires that the Chumash trail system be identified and mapped before project decisions are made to ensure that a significant and unique heritage resource is not lost or damaged.

“Given the presence of a trail system through the project area and the antiquity and preservation of the forests, the project area offers an exceptional opportunity to better understand how Chumash people related to the forest,” the letter states.

Further, the letter notes the documentation of dwarf mistletoe as medicines for both the Chumash and neighboring tribes. It cautions that removing trees because of dwarf mistletoe “places traditional Chumash plant medicines, potentially latent cultural and spiritual practices, as well as ecological knowledge in clear and present danger.”

Logging with Loopholes

The letters analyzed by ForestWatch were nearly unified in their opposition to the Forest Service’s use of loopholes, called categorical exclusions(CEs) to approve the project. Commenters overwhelmingly rejected the agency’s approach and called for increased transparency and full environmental review.

“A CE is not appropriate here,” said a letter from the Goleta Coast Audubon. “Because the project is designed to protect natural resources, it is imperative that robust science be deployed in an [environmental assessment] or [environmental impact statement] framework to demonstrate that the net effects of the work will be positive.”

A wildlife biologist with nearly half a century of professional experience including work with the Forest Service, commented in favor of some action on Pine Mountain, but said, “The proposed action presupposes that all thinning is good, and that it can therefore be justified under a categorical exclusion from further environmental analysis. This is incorrect. Not all thinning is good, and there is strong and active debate within the scientific community on where and how to go about fire-reduction actions, such as those proposed for Pine Mountain.”

“The proposed action,” the biologist continued, “which bears all the hallmarks of being rushed without adequate justification, fails to meet adequate scientific standards, fails in the court of public opinion, and fails to follow the necessary standards of administrative law.”

Both Ventura County Supervisor Linda Parks and Congresswoman Julia Brownley disputed the use of CEs and urged further environmental study or withdrawal of the project.

Public comment included multiple additional admonishments such as the agency’s failure to collaborate with stakeholders in developing the project. A retired Forest Service scientist who, among other things, worked as an environmental review coordinator, outlined additional reasons that the loophole could not be used. The California Chaparral Institute said, “The Proposal fails to satisfy the very premise of the National Environmental Protection Act … to avoid environmental degradation, preserve historic, cultural, and natural resources, and ‘promote the widest range of beneficial uses of the environment without undesirable and unintentional consequences.’ This project represents some of the worst land management practices on the National Forest.”

Wildfire Science

Several comments pointed to inaccurate portrayal of several key elements of the project, most commonly, the Forest Service’s claim that the action will “reduce potential for loss of life and property.” Several were scathing in their criticism. “I am not going to comment on one of these justifications [for the project] – threat to structures and property – other than to say it is ridiculous,” said one scientist.

The mayor of Ojai noted that “scientific studies have demonstrated that remote vegetation treatments are ineffective in protecting communities from fires that cause the majority of damage in California” and recommended “promoting defensible space requirements near homes rather than logging special and invaluable old growth forests of Pine Mountain.”

Former Ventura County Supervisor Steve Bennett reminded the Forest Service that by their own study, the fuel break would have negligible value as its priority level is number 118 out of 163 across the national forest.

Many commenters took issue with the characterization of Camp Scheideck-several cabins on the floor of the Ozena Valley about three miles from Pine Mountain—as part of an urban interface; Ojai, at 15 miles away, is the closest urban area. A biologist with 40 years of experience including work with the US Fish and Wildlife Service asked, “why one would go upslope three miles away to remove 15,000 trees to protect a community which could more effectively and with far less ecological destruction protect itself at its borders.”

A meteorologist and former firefighter in the Los Padres said, “My understanding of the wind regimes in the project area and the Ozena Valley lead me to believe that the frequency of occurrence of winds that blow from Pine Mt. to Camp Scheideck (or Ozena station) during the fire season of roughly May through November is very low. Therefore, what good would it do to build the proposed fuel break on Pine Mt. for purposes of protecting Camp Scheideck?” He further called for the Forest Service to make the project area’s wind records public.

The Wishtoyo Foundation said, “The Project has little potential to stop or slow massive wildfires that burn under extreme conditions. From just six wildfires burning under extreme conditions between 2017 and 2018, communities experienced 90% of total fire damage. These fires burnt through or jumped fuel break and fuel removal projects.”

A plant biologist and University of California Riverside PhD candidate wrote, “[t]he data for these types of clearing projects time and time again has shown no improvement in fire suppression with evidence of type conversion of the ecosystem (the nearly irreversible transition from one ecosystem type to another).”

Several scientists took issue with the Forest Service’s assertion that the area would be denuded of trees if a fire occurred. “I … question the fundamental premise that the moist, north-facing side of Pine Mountain is in danger of burning catastrophically,” said one scientist formerly with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s California condor recovery program. “In my experience, that would occur only if firefighters adopted the ‘all back and burn out’ response to any fire start in the watershed.”

It is “likely the area would burn naturally, as it is evolved to do in a mosaic pattern, and regenerate eventually based on other historic local fires,” said a wildfire ecology professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

The Forest Service’s version of wildfire history on Pine Mountain was also rigorously questioned in public comments. An ecology professor at UCSB, discussed the growth ring data that was collected with a student. Of the 40 logs they found cut as hazard trees along the road and trails—logs aged 290 to over 700 years old—they found not one that had any sign of wildfire scaring. The scientist also points to fallen trees. “I can show you multiple places where 3 and even 4 generations of treefalls are stacked, the lowermost and oldest reduced to knots, and the youngest possibly decades old. Any ground fire in the last (several) hundred years would have consumed this debris, yet there it lies.”

Forest Health

Multiple requests, both in public meetings and in written comments, were made for missing information on sensitive and nonnative species, native plant diversity and rare species present, mistletoe, species composition within the boundaries of the proposed forest, and, most persistently, existing and historical tree stand information. The data was not made available during the comment period, and was only provided after repeated requests under the Freedom of Information Act.

Many comments expressed alarm at the number of trees that the Forest Service seemed to be proposing to remove. “It is … somewhat alarming at the number of estimated trees that will be removed over the course of this project,” said Los Padres Forest Association. “We’ve seen estimates anywhere from 10,000 to 15,000+ trees that will be removed, which is quite a difference and both estimates seem high.”

The ecology professor said that the removal of so many trees would greatly increase the exposure to high winds and heavy wet snow cover in the canopy for those left behind. “By removing wind-absorbing trees (at an average loss of 35/acre) that form the denser upper segment of the canopy you will inevitably enhance damage to both the largest trees and the smaller ones left exposed.”

The plan, the scientist remarked, took no account of the regeneration crisis in (southern) California conifer forests. Extensive thinning, the ecologist and other commenters pointed out, could result in too many of the same-age trees with no next generation to replace them, or the encouragement of dense shrub growth, and could eliminate much or all existing conifer recruitment.

Goleta Coast Audubon added, “The permanent loss of ‘sky island’ conifer forests has been documented throughout southern California in recent years. Conifer forests are especially vulnerable because their trees take nearly a decade to reach reproductive maturity … Any action that disrupts the ecological succession may destroy future seed sources and limit the potential for future regeneration. These actions should not be taken without extensive environmental review.”

Comments also pointed to missing critical project details on where thinning is needed within the project area, which species will be targeted, the age and distribution of trees proposed for cutting. Requests were made for more specific information on the treatments being proposed, which treatments would be done where, and the extent of those treatments.

The wildfire ecologist said, “The project plan refers to the forests of Reyes Peak as being ‘overstocked.’ This unfortunate terminology is not scientifically sound and implies that there is an ideal stocking (density) that should be maintained in these forests.” The scientist and others questioned this assumption, as well as basing that desired condition based on a small sample outside of the project area from the 1930’s.

The Kern Chapter of the California Native Plant Society (CNPS) voiced concern that removing fire resistant trees, drying out forest floor, and spreading flammable invasive plants may increase wildfire risk. The CNPS state office reiterated many of these concerns as well as the need for the project to “consider the heterogeneity of the forest and revise the current tree density objectives.” The group went on to say, “The consequences of this Project potentially outweigh the intended fire and disease prevention objectives. Thus, an EIS should be prepared to ensure that detrimental and irreversible impacts to the Project area are avoided.”

Removing trees and temporary roads also increase access for human disturbance long after the project is complete, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Habitat loss and invasive plants are a leading cause of native biodiversity loss,” and the project is likely to do both, the agency said.

Impacts to Roadless Areas and Proposed Wilderness

Several commenters criticized the plan’s failure to mention the significance of the long undisturbed mountain top. “Not only are the Project’s claims that this area has low wilderness value unfounded, they are completely contradictory to published evaluations completed by the US Forest Service,” said the Wishtoyo Foundation. “The Los Padres National Forest Service has [also] failed to inform the public of the true nature of impacts to this inventoried roadless area(IRA),” or provide “evidence that the Project will not have adverse effects” on the IRA. Multiple organizations expressed similar concern for the IRA and proposed wilderness including Channel Islands Chapter of CA Native Plants Society (CNPS), California Wilderness Coalition, Western Watersheds, and PEW Charitable Trusts.

“The Project is adjacent to the Sespe Wilderness and in close proximity to the Matilija and the Dick Smith Wilderness areas,” Wishtoyo said. “The removal of vegetation and habitat in the Project area reduces habitat viability and connectivity between these wilderness areas. Since 41% of the Project area lies in inventoried roadless area and a significant percentage lies within two proposed wilderness areas, tree stands should not be evaluated for their ability to produce timber volume. Dwarf mistletoe improves habitat variability and avian biodiversity in an area valued as potential wilderness and it should be managed as such.”

Dead, Dying, and Diseased Trees

A scientist formerly with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agreed, “Since Pine Mountain is not a commercial timber-producing forest, why should natural ecological processes be considered a forest management problem?” The scientist and other said that claims about insect damage, disease and the threat to forest health on Pine Mountain were not well supported by relevant information and experience. A wildfire ecologist said, “There are no data provided to indicate that the health of this forest is in peril or in need of improvement and “health” is not defined.”

The Channel Islands Chapter of CA Native Plants Society (CNPS) also expressed frustration at the absence of data about dead trees that the agency said were necessary to remove. Dead trees, known as snags, “play an important role in the forest ecosystems, especially for cavity nesting birds” the group said.

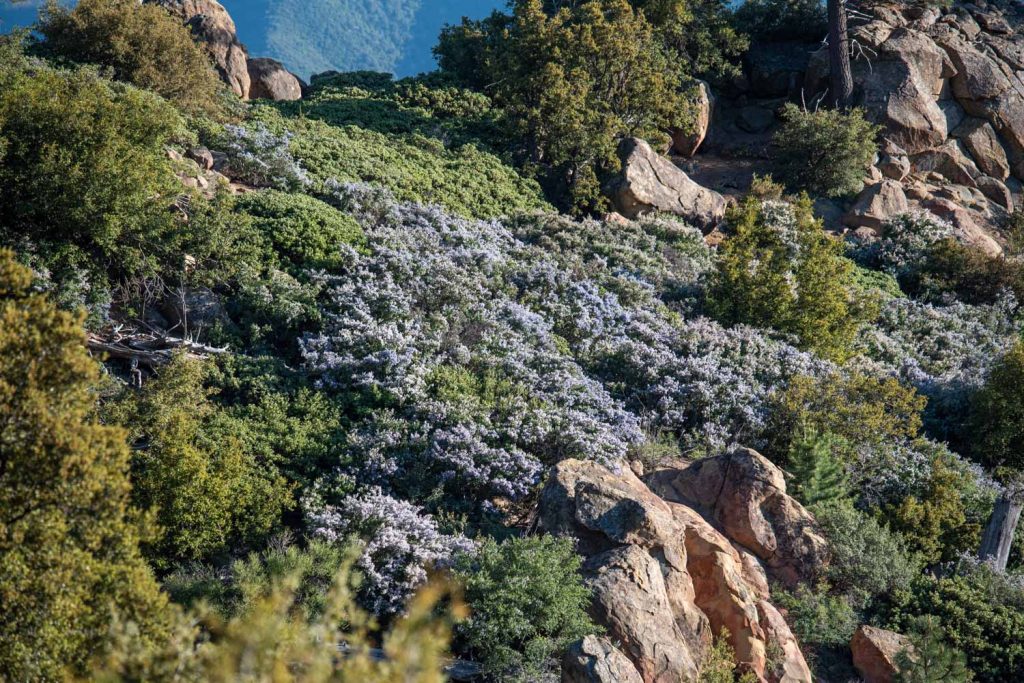

Chaparral Impacts

The Channel Islands Chapter of the California Native Plant Society and others expressed strong concerns about grinding up large swaths of native chaparrall due to its likelihood to result in a dramatic change in the overall plant composition in the project area. Many chaparral plants are dependent on wildfire to reseed. If they are cut and do not experience wildfire within the amount of time to which they are adapted, some plants cannot regenerate and can die out of an ecosystem. This can cause profound impacts to plant communities and wildlife.

“The removal of native chaparral and coniferous vegetation will only increase wildfire risk by removing fire resistant vegetation and plants that have adapted to California’s natural fire regime,” said the Wishtoyo Foundation.

The California Chaparral Institute agreed. “The Proposal’s classification not only contradicts itself, but is contrary to fire science and plain logic regarding how fire interacts with chaparral.”

Wildlife Habitat

The scientists identified multiple impacts to protected wildlife, making the project ineligible for the loophole and requiring full environmental review. “Absent expert guidance, the project will inevitably harm important wildlife habitat,” said a wildlife biologist. The Santa Barbara Audubon Society concurred. “In short,” the group said, “the Project would greatly damage and diminish unique habitat needed to maintain and sustain many native and sensitive bird species.”

California’s Dept of Fish and Wildlife also made note of the many endangered and vulnerable plant and wildlife species found in the project area or known to frequent it. The California Native Plant Society, the California Wilderness Coalition, and other botanists identified more than 16 species that are restricted or nearly restricted to Pine Mountain, and at least 23 species as rare or sensitive.

“Pine Mountain is one of only six high-elevation conifer forest systems in the Western Transverse Range of Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties, four of which have already been impacted by fire or logging.” said the Goleta Coast Audubon Society. “The activities described in the proposal will damage fragile habitat essential to an array of bird species not found within our area outside these few peaks.”

Many commenters urged in-depth investigations of plants or animals that are restricted in range and may be species of special concern in California or Southern California, including the flammulated owl, northern saw-whet owl, green-tailed towhee, and fox sparrow, among many others, but none more frequently than the spotted owl. Several California condor and spotted owl experts said that the project includes habitat for both species.

The scientists urged the Forest Service to recognize current scientific information and the agency’s own management direction for California spotted owl habitats in southern California. They pointed to the plan’s failure to incorporate the Forest Service’s overall spotted owl conservation strategy to evaluate the project.

Other Environmental Harms

All of the scientists identified ways that the project could cause harm to Pine Mountain’s forests, including, and most commonly, through the introduction and nurturing of invasive grasses and other plants that would choke out native species and increase the risk of ignition and fire spread. Many were critical of a lack of a plan to address the issue.

California’s Dept of Fish and Wildlife said, “the Proposal does not adequately analyze the potential for adverse impacts” such as soil compaction caused by industrial equipment and the altering of microclimatic conditions that could permanently damage whole plant communities.”

A former forest Firefighter and botanist with the Bureau of Land Managemen and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said, “This document is very incomplete, and the public is not currently able to even assess what the project consists of, and how it will affect the current environment.”

Los Padres Forest Association and others expressed concern “over how the downed trees will be piled up, what means will be used to move them, timeframe for completion and who will monitor this process.” The group said, “We’ve seen somewhat similar activities at Figueroa Mountain where huge burn piles are spread out across the landscape for months if not years waiting to be burned. It would be great to avoid a similar fate up on Pine Mountain.” It was not alone in asking for “some assurances that there will be some management and oversight when the actual logging portion of the project occurs. It would be a shame to have additional unnecessary trees dropped due to a misunderstanding or lack of oversight.”

Impacts to Recreation

Several commenters remarked that information about the current use or value of the site was missing from project documents. The California Wilderness Coalition was one of several that stressed the area’s scenic and recreation value in urging of the agency to prepare an EIS.

Steve Bennett, currently representing the region in the California legislature, said, “The project would all but eliminate the recreational value of the area during its construction phase, and the proposed substantial tree removal would permanently significantly degrade the most attractive feature of this pristine area.” He further suggested that the project would cause economic harm to businesses in gateway communities.” A letter signed by nearly 100 local businesses backed up this claim.

A commenter from Simi Valley said, “[p]rotecting Pine Mountain is important to me because it provides a spectacularly beautiful outdoor space for me and my family to escape to.”

“Even though I live in Los Angeles, I’ve become inextricably connected with the greater California landscape in my 13 years here, including the Los Padres NF,” said one commenter. “I feel at peace, at home connected with the flora and fauna, air, dirt, and water. We are rapidly losing our natural places to development and extractive industries – irrevocably changing not only the health of our wildlife, but also the health – and happiness – of our people.”

“I live in Ventura county and have been up to these mountains several times,” said a commenter from Camarillo. “It is difficult to get to other pine forests because of the distance to travel. I love the big pines. They make the problems disappear for just a little while in our lives when we visit them. So Please leave them be to grow as majestic as can be, we need these in our world.”

A UCSB professor with 30 years of experience as a resource economist said that the proposal did not account for the loss of recreational benefits. The professor quoted from a climbing guide that describes Pine Mountain as “one of the most stunning and far-reaching bouldering areas in Southern California.” The professor, who has authored or co-authored peer-reviewed papers on the benefits that people derive from outdoor recreation said, “A large part of the appeal of Pine Mountain are the large, old trees that provide shade and scenic beauty.” Included in the letter were data that said the economic benefit of several popular rock climbing sites in the US as upward of $208 million dollars per year to over $900 million. The professor identified a 1990 study that said that wildlife viewing in the Los Padres National Forest provides benefits to recreationists worth $22 per person per day. Losses of these benefits, he said, were not accounted for in the project proposal.

The Access Fund, a national organization that seeks to keep climbing areas open and conserves the climbing environment, said, “there are an estimated 160 individual, high-quality climbs on boulder formations on Pine Mountain ridge that draw climbers from across southern California.”

Comments are closed.