Eumetopias jubatus

- Threatened – Endangered Species Act (1990)

- Near Threatened – IUCN Red List (2016)

- Protected Species – Marine Mammal Protection Act

Steller Sea Lions in the Los Padres National Forest

As strange as it might sound, Steller sea lions can be seen within the Los Padres National Forest along 10 miles of the southern rocky Big Sur coastline. The low rock islands and unapproachable beaches that line the Big Sur coast are frequented by several species of pinniped marine mammals such as sea otters, sea lions and seals. Both the California sea lion and populations of Loughlin’s (eastern) Steller sea lions can be seen here hauling on rocks to sleep on or laying in the sun. Most of the sea lions in this area breed in large colonies at Ano Nuevo Island north of Santa Cruz after giving birth during the early summer months of June and July. They can be seen returning from the shallow protected lagoons of Baja California and mainland Mexico after giving birth to young in March and April. The best time to see Steller sea lions in the Big Sur area is during the later summer months of August, September and October where they can be found along the shoreline within the Los Padres National Forest’s Monterey Ranger District.

Biology

Steller sea lions are very skilled and opportunistic marine hunters. Inhabiting the cold arctic waters of the North Pacific Ocean, they prey on a wide range of fish species including salmon, halibut, cod, herring and rockfish along with several cephalopod species such as squid and octopus. Being near the top of the marine food chain, Steller sea lions are generally only susceptible to predation by humans, killer whales and great white sharks.

Pinnipeds such as sea lions, walruses and seals exhibit a behavior known as hauling-out, where they leave the water to explore sites on land or ice between periods of foraging activity. Hauling-out is necessary in order for sea lions to mate, providing them with an opportunity to rest, socialize and thermoregulate all while avoiding predators. Non-reproductive aggregations are simply known as “haul-outs” while reproductive aggregations onto land or ice are termed “rookeries.”

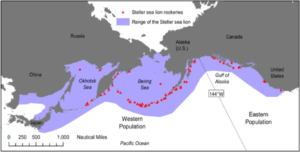

Often confused with the California sea lion, there are several ways to distinguish between the two. Visually, the average Steller sea lion is more than half the size of the California sea lion and has a distinguishable short, broad and blunt nose compared to the long, pointy and narrow nose of the California sea lion. The Steller sea lion is comprised of two recognized subspecies determined by range: the eastern subspecies found along much of North America’s west coast (including California) and the western subspecies found along coastlines between Alaska and Japan.

A fully-grown adult male weighs an average of 1250 lbs while the average female weighs around 550 lbs. Pups weigh an average of around 50 lbs at birth and can be weaned at one year, although there have been documented reports of nursing up to 4 years old. An interesting fact about the Steller sea lion is that females can live up to 30 years while males rarely survive past their mid-teens. Steller sea lions become sexually mature at 3 to 7 years of age, although males are not mature enough to defend territory and acquire mates until at least the age of 9. Males arrive at rookeries in May and fight to claim and maintain territory for the following two months. Breeding occurs shortly after the pups are born during June and July and the females, with an incubation period of 11 and ½ months, return the following year to give birth and breed again on land.

Threats

Historically, the Steller sea lion has faced much predation pressure from humans as they were hunted for their meat, fur and blubber. For Alaskan native peoples, these animals served as a staple food and natural resource for their communities for thousands of years. In Alaska, tools crafted from sea lion bones were found in prehistoric archaeological sites.

Harvesting of Steller sea lions continued well into the early 20th century until sharp declines in the western populations raised significant concerns in the 1970’s with populations decreasing by 75% between 1976 and 1990.

In the United States it is illegal to hunt sea lions and both subspecies that compose the Steller sea lion population are protected under federal law. According to experts that study changes in their populations, a large number of Steller sea lions are continually poached annually, contributing to discrepancies in their population numbers. A successful method to offset this illegal activity has been awarding monetary rewards for the reporting of illegal main mammal hunting activity. Other threats to Steller sea lions include ship strikes, interactions with fisheries, habitat degradation due to contaminants and pollutants and offshore oil and gas extraction.

Conservation Efforts

The species was listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act in 1990. A recovery plan was developed for the Steller sea lion in 1992 that designated critical habitat for the species as a 20 nautical mile buffer around all major haul-outs and rookeries along with three major foraging sites. A revised recovery plan was issued in 2008, which discussed separate recovery action plans for both subspecies.

In 2013, the eastern subspecies of the Steller sea lion was delisted due to the successful recovery of the eastern populations, having been estimated to increase 243% over the last 40 years due to the conservation benefits and protection provided by Endangered Species Act. However, the western subspecies of Steller sea Lions in the United States has been listed as Endangered since 1997.