Bird #526 seen flying overhead. Photo courtesy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Santa Barbara Zoo.

Recently, a California condor was found dead just outside of the northeastern portion of the Los Padres National Forest near Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge in Kern County. While the death of any of condor — which only number 300 in the wild — is terrible news, this one was particularly tragic: condor #526 was killed by a gunshot.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s law enforcement arm is currently investigating the shooting of #526, which they believe happened on private land sometime in July. They offered a reward of $5,000 to anyone with information that may lead to an arrest. The Center for Biological Diversity has pledged $10,000 that reward, tripling it. Anyone with information should call the Service’s Office of Law Enforcement at 916-569-8476.

Shooting deaths for California condors, while uncommon, do seem to be on the rise. According to the federal biologists, nine condors have been shot and killed in the wild since 1992 when the agency’s Condor Recovery Program began reintroducing California condors back into the wild. Of these nine, five have occurred since 2009.

The life of #526 started when she hatched on May 4, 2009 in a cliff-side nest near Agua Blanca Creek in the Sespe Wilderness of the Los Padres National Forest. Her mother was bird #192, who sadly was found dead from lead poisoning at nearby Tejon Ranch in 2015, and her father was the famous bird #21 or AC-9 — the oldest condor in the wild at the time. When biologists captured the remaining 22 wild condors in the 1980s, AC-9 was the last to be taken from the wild. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists successfully caught him on Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge in 1987. He went on to become a key bird in the captive breeding program before his release back into the wild in 2002. The bird paired with #192 in 2004, and they successfully fledged several condors, including #526. Unfortunately, AC-9 also went missing in the wild in 2016 and is presumed dead. The tragedy that has afflicted this family of condors demonstrates just how tough it is for endangered condors to survive in the wild.

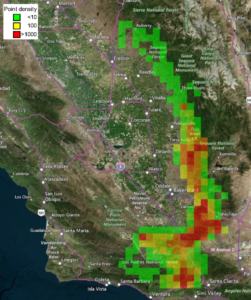

Activity of bird #526 as shown by tracking data collected by the Fish and Wildlife Service since 2014 when she was fitted with a GPS transmitter. Red and yellow areas indicate more frequently-visited locations. Map courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Condor #526 was like many other condors from the Southern California flock. She spent much of her time in the Sespe Wilderness and Sespe Condor Sanctuary, as well as Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge, and the Tehachapi Mountains. She even took occasional jaunts as far north as Sequoia and Sierra national forests. She was also one of the 28 condors who have been roosting in and near the site of a proposed commercial logging project on Tecuya Ridge for years. She last roosted there in September of 2017. Her father, #21, also roosted along the ridge before going missing. We are continuing to work hard to ensure that condors and their roosting habitats are protected.

We are also working to reduce the incidence of lead poisoning — which killed #526’s mother and likely her father as well. Condor #526 was taken to the Santa Barbara Zoo five times in her relatively short life to be treated for elevated blood lead levels. Lead poisoning is still the leading cause of death for endangered condors, which often eat carcasses shot and contaminated with lead bullets and left in the wild. A ban on lead ammunition for hunting in California has been gradually phased in since 2013. By July 2019, hunters throughout the state will have to use non-lead ammunition for all hunting activities, a regulation that will reduce lead poisoning in condors and other carrion-eating birds.

While the recovery of California condors has been mostly a story of success, the death of #526 and other birds over the years shows that the species is still not fully safe from extinction. Now, more than ever, we must be vigilant in our work to protect this important and magnificent species that truly defines our region.

Rest in peace, #526.

Comments are closed.