Accipiter gentilis

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

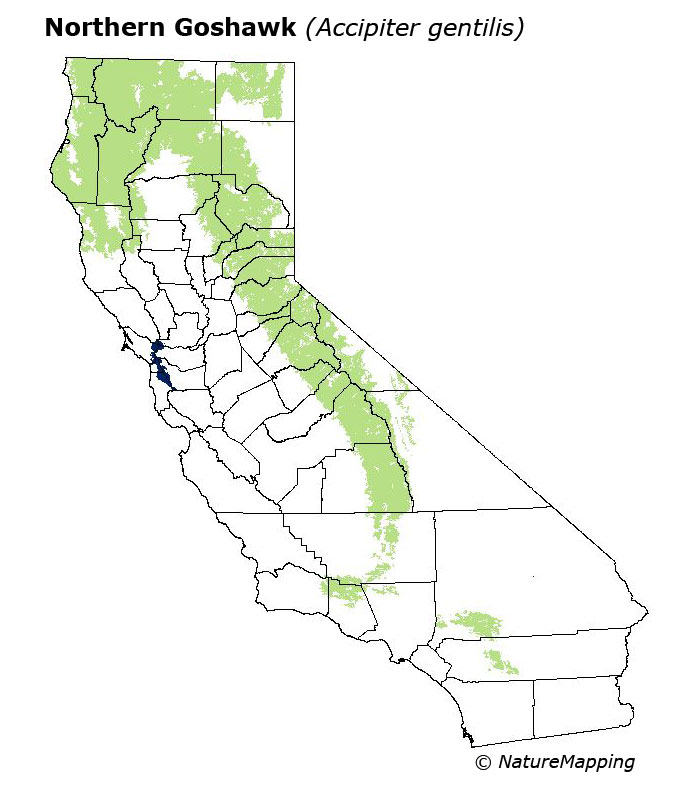

The northern goshawk is found across Eurasia and North America, and is the largest of all goshawk species. In California, the northern goshawk only breeds in the northern mountain ranges and in the southern portion of the Los Padres National Forest around Mt. Abel, Mt. Pinos, Frazier Mountain, and the Tecuya Range in northern Ventura County. Well-distributed across their core breeding range in the north, the birds are quite rare in southern California.

Goshawks build their nests in mature and old-growth forest stands, preferring trees like ponderosa pine, Jeffrey pine, white fir, and lodgepole pine. Northern goshawks are monogamous (and solitary outside of the breeding season) with pairs typically meeting at nesting territories by February each year. They sometimes migrate in the winter if food is scarce, but often will remain near nests year-round in the warmer southern climates. Breeding typically begins in April and lasts into August, but can begin as early as February and extend through September.

Northern goshawks prey on a variety of animals including squirrels, hares, grouse, woodpeckers, and other raptors. They are considered sit-and-wait predators, perched on branches scoping the landscape for food, often switching perches numerous times during the hunt. Large snags and downed logs are important because they support prey species like small mammals and cavity-nesting birds upon which goshawks depend for food.

Northern goshawks are wide-ranging birds, with a breeding pair defending a territory ranging from 1,500 to 8,500 acres. Their large home-range, combined with their relatively low reproductive rate, make northern goshawks particularly vulnerable.

Threats

Northern goshawk populations in California are poorly understood, and comprehensive surveys have not been completed. A recent estimate for goshawks statewide was only 1,000 breeding territories (approximately 2,000 birds). Active nest sites were last recorded on Mt. Abel and Mt. Pinos in the late 1980s, but these areas have not been surveyed recently. A goshawk family was recently observed on Frazier Mountain in July 2011, indicating that goshawks are nesting on Frazier Mountain as well.

Northern goshawk range in California. A substantial amount of prime habitat can be found in the Mt. Pinos area of the Los Padres National Forest. Map courtesy NatureMapping.

The primary threats facing northern goshawks are habitat degradation and loss from wildfires, fire suppression and vegetation treatment projects, and timber harvest, which removes nesting trees and the downed logs on which goshawks rely for foraging. This makes projects on forest land that remove large old-growth timber particularly harmful to goshawk populations.

Small numbers of goshawks are allowed to be collected for falconry in California, but biologists believe that the current collection levels do not affect statewide population numbers.

Conservation

The best way to ensure that goshawks continue to survive in the Los Padres National Forest is to protect and restore the mature conifer forest habitats on which the birds depend.

According to the Forest Service, the greatest concern for goshawks is the prevention of large-scale wildfire plus the restoration of forested vegetation types. To accomplish these goals, the Forest Service has imposed several Best Management Practices including retaining large trees and down logs for prey species, and limiting harmful activities within 1/4 mile of nest sites during the breeding season.

No comprehensive goshawk surveys have been conducted in the Los Padres National Forest, so while these practices are a good first step towards protecting the birds, a more solid understanding of goshawk distribution and habitat use in southern California is still needed. The Forest Service has recognized this point, stating:

More information is needed on where goshawks may nest in the mountains of southern California. The breeding population is clearly small. It’s not known why goshawks numbers are so low in southern California. Efforts to maintain the integrity of breeding territories of northern goshawks cannot be made until their locations are known. To ensure the goshawk’s existence will require the restoration of these degraded habitats and the protection of native processes.

Additionally, from 2005 to 2011, the Forest Service proposed several commercial timber sales in northern goshawk habitat in the Los Padres National Forest. ForestWatch has worked to stop these projects, encouraging forest officials to focus instead on non-commercial forest thinning, targeting small-diameter trees while leaving large trees, snags, and downed logs in place for the benefits they provide to goshawks and their prey. In 2012, the Forest Service agreed to incorporate ForestWatch recommendations to protect northern goshawks on Frazier Mountain.

The Forest Service again announced two large commercial logging projects in prime northern goshawk habitat near Mt. Pinos in 2018. The agency proposed the project without any comprehensive environmental review that would determine potential impacts to this and other species in the area. ForestWatch submitted detailed comments requesting a full environmental impact statement be conducted and facilitated over 600 comments on the projects from the public.

ForestWatch will continue to work with forest officials to ensure that the goshawks in the Los Padres National Forest receive the highest level of protection, and that surveys are conducted to better understand where goshawks are nesting so that their habitat can be protected.