Arctostaphylos

More than sixty species of manzanita occur in California, twelve of which are found in the Los Padres. They range from shrubs only a few feet tall to some as tall as twenty feet, and are all characterized by reddish or orangish bark, gnarled trunks, and waxy leaves. The plants produce bell-like white-to-pink flowers in the winter and spring, and then produce apple-like fruits, giving them their name manzanita, or “little apple” in Spanish. Native Americans would often use these fruits to make meal and cider, and much of the wildlife of the chaparral, including bears, deer, and squirrels, depend on these fruits for food throughout the summer.

More than sixty species of manzanita occur in California, twelve of which are found in the Los Padres. They range from shrubs only a few feet tall to some as tall as twenty feet, and are all characterized by reddish or orangish bark, gnarled trunks, and waxy leaves. The plants produce bell-like white-to-pink flowers in the winter and spring, and then produce apple-like fruits, giving them their name manzanita, or “little apple” in Spanish. Native Americans would often use these fruits to make meal and cider, and much of the wildlife of the chaparral, including bears, deer, and squirrels, depend on these fruits for food throughout the summer.

Manzanitas are adapted to particular fire patterns. While a few can resprout from burls at the base of the shrubs, all have seeds that are stimulated to germinate by chemicals in smoke or charred wood. This does not mean, however, that manzanitas “need” fire. It is a common misconception that chaparral plants such as manzanitas need fire or are “fire dependent.” Manzanitas can live for a very long time—hundreds of years by some accounts—and their seeds can survive in the “seedbank” for decades. This means that the plants never really need fire, but they are prepared for it when it does occur, so long as it doesn’t occur too frequently.

Today, chaparral is facing a different environment than it did before Europeans arrived in California. Whereas lightning used to only start fires once every few decades to centuries along the Central Coast, now human-caused fires are occurring more frequently, and this is having a negative effect on manzanitas and chaparral in general. When manzanitas have time to build up an adequate seedbank over many decades, there are sufficient numbers of post-fire seedlings to restore the population. Increased fire frequencies prevent this from occurring. In addition, with those few manzanitas that sprout from burls following a fire, a second fire soon after the first can kill the new sprouts and permanently kill the burl.

This increased frequency of fire is especially harmful to our rare and endemic manzanitas here in the Los Padres, including Little Sur manzanita, Santa Margarita manzanita, Santa Lucia manzanita, Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita, and Refugio manzanita, which each have only a few populations occurring in the Los Padres and lack the ability to resprout following fire. The U.S. Forest Service has classified each of these six rare manzanita species as “sensitive,” granting them special protections.

Sensitive Manzanita Species

Arroyo de la Cruz Manzanita

Arctostaphylos cruzensis

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

- Rare Plant Rank 1B.2 – California Native Plant Society

- G1 Critically Imperiled – NatureServe (2017)

Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita is endemic (found nowhere else) to coastal areas from northwest San Luis Obispo County to Southern Monterey County and found in only two areas on the Los Padres National Forest. This manzanita is small compared to more common manzanita species, reaching less than a few feet in height, and is described as a “spreading” evergreen shrub with reddish, peeling bark and overlapping leaves. It does not have a basal burl, however, and thus does not resprout after fire, making it more sensitive to fire than some other manzanitas. Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita occurs in a variety of habitats, including chaparral, coastal scrub, conifer forest, and valley-foothill grassland.

Little Sur Manzanita

Arctostaphylos edmundsii

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

- Rare Plant Rank 1B.2 – California Native Plant Society

- G2 Imperiled – NatureServe (1993)

Little Sur manzanita is found in only a few places in the Los Padres. It is endemic to Monterey County, only from Garrapata Creek to Pfeiffer Point along the Big Sur coast. Little Sur manzanita is described as a “low-mounded, small-leaved” manzanita. As with Arroyo de la Cruz, Little Sur manzanita grows less than a few feet tall and can grow wide, up to 11 feet across. This species is characterized by shiny leaves with a yellow hue and compact clusters of flowers. Little Sur manzanita occurs in coastal bluff scrub and maritime chaparral on sandy terraces where it is exposed to high winds, sea spray, and fog.

San Gabriel Manzanita

Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. gabrielensis

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

- Rare Plant Rank 1B.2 – California Native Plant Society

- G1 Critically Imperiled – NatureServe (2016)

Santa Lucia Manzanita

Arctostaphylos luciana

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

- Rare Plant Rank 1B.2 – California Native Plant Society

- G3 Vulnerable – NatureServe (2016)

Santa Lucia Manzanita is endemic to San Luis Obispo County. It is only found in the southern portion of the Santa Lucia mountain range, and occurs in five areas of the Los Padres. While overall the species is rare on the forest, where it does occur it can be quite abundant, forming large stands of purely Santa Lucia manzanita. This manzanita is distinguished by overlapping, whitish leaves, smooth bark, and soft, short hairs on young branches. It grows larger than Little Sur or Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita, reaching a height of over 16 feet, but as with these other species, lacks a basal burl and regenerates only by seeding. Santa Lucia manzanita is found in chaparral and woodland areas, on shale substrates and outcrops on hill slopes.

Santa Margarita Manzanita

Arctostaphylos pilosula

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

- Rare Plant Rank 1B.2 – California Native Plant Society

- G2 Imperiled – NatureServe (2016)

Similar to Santa Lucia manzanita, Santa Margarita manzanita is endemic to San Luis Obispo County. It ranges from the southern Santa Lucia Mountains to the hills between San Luis Obispo and Arroyo Grande, and is found in two locations on the Los Padres National Forest. Santa Margarita manzanita is characterized by dark, smooth, red-brown bark, twigs with long or short bristly hairs, and gray- to yellow-green leaves. It is found with chamise and manzanita chaparral, as well as occasionally with conifers.

Refugio Manzanita

Arctostaphylos refugioensis

- Petitioned – Endangered Species Act (2017)

- Sensitive – U.S. Forest Service

- Rare Plant Rank 1B.2 – California Native Plant Society

- G3 Vulnerable – NatureServe (2017)

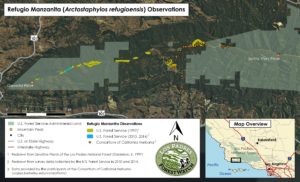

Refugio manzanita is endemic to the Santa Ynez Mountains of Santa Barbara County. It is only found between 1,000 and 3,200 feet in the Santa Ynez Mountains between Gaviota Peak near Highway 101 and Santa Ynez Peak just east of Refugio Road. It has one of the most limited ranges of all manzanita species in the world. The Refugio manzanita can grow to 15 feet tall and 11 feet wide, and is characterized by 1.2-1.8 inch-long, heart-shaped, overlapping leaves. As with the other rare manzanitas on the forest, refugio manzanita does not have a basal burl. The species is found in chapparal, sometimes mixed with woodland, in sandstone areas on south-facing slopes and rideglines. Nearly all the refugio manzanita on the forest was affected heavily by the 1955 Refugio Fire, but the populations appear to have recovered well.

Observations of Refugio manzanita, which are entirely within a narrow range along the Santa Ynez Mountains between Gaviota and Santa Ynez Peaks. Click for an enlarged map.

This manzanita species has been threatened by largescale vegetation clearing projects such as the proposed Gaviota Fuel Break in 2016, which would have cut through the heart of most of the remaining populations of the species had it not been halted by a lawsuit and resulting legal settlement involving ForestWatch, the California Chaparral Institute, and the U.S. Forest Service. Some populations also grow on private land in the Refugio Pass and are at risk of being removed along with their prime habitat due to land development. Furthermore, the spread of invasive species in the Santa Ynez Mountains poses a threat to the Refugio manzanita’s habitat and chance of survival.

Because of these threats, ForestWatch and the California Chaparral Institute submitted an official, detailed request to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the Refugio manzanita as endangered in 2017. Efforts to secure federal protection for this rare plant date all the way back to 1975, when the Smithsonian Institution petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list several species, including the Refugio manzanita, under the newly-enacted ESA. However, due to lack of information on the relatively recently-discovered species at the time, no action was taken. Now, 42 years later, information about the rarity of the species and the many threats it faces have contributed to this new request for endangered species status. In addition, the California Native Plant Society — the foremost authority on native plants in California — considers the Refugio manzanita as “rare, threatened, or endangered in California and elsewhere” as well as “fairly endangered in California.” The U.S. Forest Service has also classified the Refugio manzanita as a “sensitive species” because of its vulnerability and declining population numbers.

Listing under the Endangered Species Act would afford the plant and its habitat more protection from harm and would result in the preparation of a recovery plan to ensure that stakeholders take whatever steps they can to safeguard this unique species.

Protecting Rare Manzanitas and Chaparral in the Los Padres

ForestWatch is currently working to protect manzanita on the Los Padres, as well as chaparral in general, from overly-frequent burning and fuel treatments like masticators that could destroy this important ecosystem in the long-term. We are also working to improve fire management on the Los Padres National Forest to better protect rare species, sensitive chaparral communities, and wildlife. Lastly, we are working to educate the community about fire in the Los Padres through our series on “Fire Ecology in the Los Padres National Forest.”

Manzanitas of the Los Padres National Forest

- Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita (Arctostaphylos cruzensis) — Santa Lucia Mountains

- Eastwood’s manzanita (Arctostaphylos glandulosa) — widespread

- Big Berry manzanita (Arctostaphylos glauca) — widespread

- Hoover’s manzanita (Arctostaphylos hooveri) — Santa Lucia Mountains

- Santa Lucia manzanita (Arctostaphylos luciana) — Santa Lucia Mountains

- San Luis Obispo manzanita (Arctostaphylos obispoensis) — Santa Lucia Mountains

- Parry’s manzanita (Arctostaphylos parryana) — Sierra Madre Mountains

- San Gabriel manzanita (Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. gabrielensis) — Sierra Madre Mountains, San Rafael Mountains

- Santa Margarita manzanita (Arctostaphylos pilosula) — La Panza Range

- Pointleaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos pungens) — widespread

- Refugio manzanita (Arctostaphylos refugioensis) — Santa Ynez Mountains

- Woolly leaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos tomentosa) — Santa Lucia Mountains