The Los Padres National Forest is home to small stands of towering coast redwoods in Big Sur (top) but is dominated by the shrubby chaparral ecosystem throughout most of the forest (bottom). Photos by Bryant Baker.

A Unique Landscape

Our region is home to some of the most unique ecosystems in the country. From the southern stands of coast redwoods sheltered between dry mountains along the Big Sur coast to the chaparral-covered slopes of the Topatopa Mountains near Ojai and Ventura — the Los Padres National Forest and nearby public lands have an incredible diversity of plants and wildlife that can only be found in our little corner of California. This mix of terrain and a dry Mediterranean climate is what creates the blend of chaparral and pockets of mixed-conifer forests found across our region.

Each year after the rainy season ends, a long and dry summer and fall result in conditions suitable for wildfires to spread once they are ignited. Fire season is one that central coast residents have come to know all too well. But why does our area burn? Is what we are experiencing natural? What is fueling the frequency and intensity of the fires in recent decades? And how do we protect our communities?

These are some of the questions we have been tackling for over a decade using the best available science. Below we look at the answers to some of these questions and how we can move forward to best protect people, property, and ecosystems.

Why Central and Southern California Burn

Our region is characterized by a Mediterranean climate: mild, wet winters followed by dry, hot summers. In the several months following the last rain, humidity in the region steadily drops — especially inland. These dry conditions create a perfect environment for wildfire to spread once ignited. Much of the vegetation covering our mountains and foothills is part of a unique ecosystem called chaparral, and over time, it has adapted to these climactic conditions.

Chaparral consists of hardy shrubs and other plants that can tolerate the long summers with no rain and the constant sun. Plants like chamise, ceanothus, scrub oak, manzanita, sumacs, and many other species of evergreen shrubs cover the sun-beaten slopes of the mountain ranges crisscrossing the area. These species are adapted to cope with drought and extreme sun exposure. More importantly, these species are adapted to infrequent but high-intensity fire. Utilizing special mechanisms such as resprouting from burls and roots in the soil or having seeds that only germinate when exposed to chemicals in smoke, chaparral plants are able to recover following a wildfire.

There are many misconceptions about the role of wildfire in chaparral ecosystems, and how our communities should best prepare to live amongst this fire-prone landscape. Fire here plays a different role than it does in conifer forests, and it is important to distinguish the two ecosystem types.

Natural Fire Ecology

We often hear that chaparral is “supposed to burn,” but that doesn’t tell the whole story. Before humans settled this area, we know from a variety of scientific evidence that chaparral burned on average every 30 – 150 years. Different mountains and areas burned more or less-frequently than others, but ultimately the chaparral communities of this part of California burned two to three times per century or less. This is in contrast to mixed-conifer forests in California, which historically burned one or two times every 20 years. Some plants like manzanitas have been found to be well over a century old in chaparral communities. That’s right, old growth chaparral isn’t a fantasy — but very few stands remain. In a time when there is a lot of talk about prescribed burns, fuel load reduction, forest thinning, and brush-clearing, it is easy to forget that if it weren’t for humans, wildfires would only ignite by lightning strikes. The Los Padres National Forest has one of the lowest incidences of lightning-ignited fires in the western United States — less than 3% of the wildfires in our region since 1917 were caused by lightning.

Decades-old chaparral along the Santa Ynez Mountain Crest near Gaviota Peak is naturally dense. Here you can find manzanitas (including the rare Refugio manzanita), ceanothus, chamise, scrub oak, and many other species that provide vital habitat for birds, kit foxes, bobcats, mountain lions, and other wildlife. Photo by Bryant Baker

However, once wildfires start in the chaparral-covered hills around our cities, they are naturally intense and burn every part of the shrubland community. These are known as a crown fires because they burn both the understory and the canopy of the ecosystem. Crown fires here are completely normal, typically replacing entire stands of chaparral at once — and chaparral species are adapted to them. Once a wildfire blazes through an area, these shrubs immediately begin their post-fire cycle: “fire followers” quickly emerge, scrub oaks resprout from their root systems, many manzanita species resprout from underground burls, and ceanothus seeds germinate quickly in the charred soil. This is a process best left unaided as large burned areas are difficult to restore by planting shrubs and dispersing seed due to the precise timing, species composition, and conditions needed to successfully restore native species assemblages in burned areas. Of course, we like to monitor these areas in the years following a fire for invasive species such as Cape ivy, yellow starthistle, Spanish broom, and others, removing infestations when we can.

There is one major aspect of fire in our region that isn’t natural, however: increased frequency.

Fire Frequency

Some of the largest and most destructive wildfires affecting the Los Padres National Forest were started by human activity. The 1985 Wheeler Fire was started by an arsonist, the 2006 Day Fire was started by someone burning trash, the 2003 Piru Fire and the 2007 Zaca Fire both started because of sparks from machinery being used near dry vegetation, the 2009 Jesusita Fire ignited because of sparks from a weed whacker being used for unapproved trail maintenance, and the 2016 Soberanes Fire was the result of an illegal campfire. Combined, these fires burned over 600,000 acres of both private and public land and destroyed hundreds of buildings. But if they had not ignited from human activity, those fires would not have occurred.

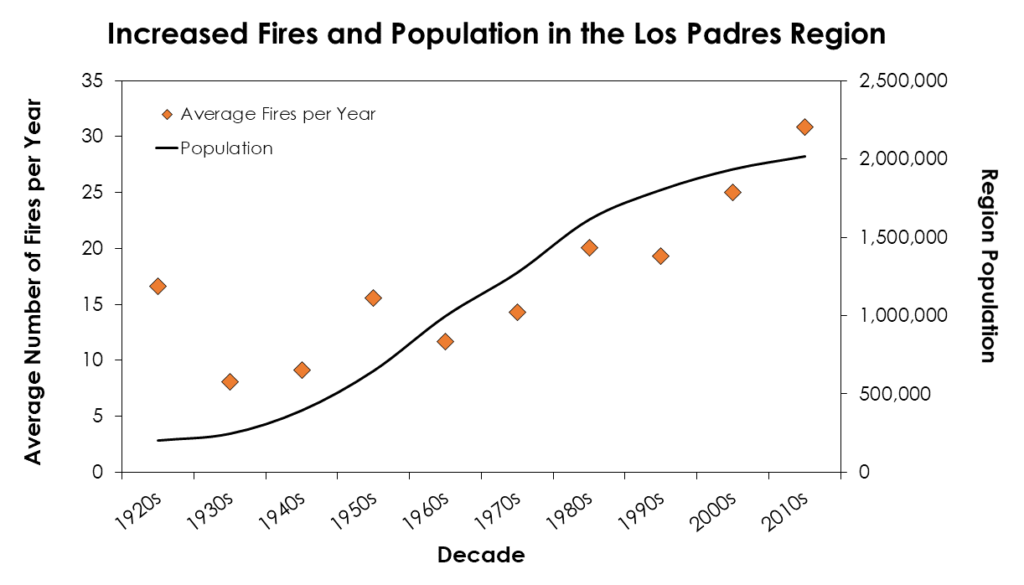

Average number of fires per year during each decade since record-keeping began in the Los Padres National Forest Region. We define this area as Monterey County, Santa Barbara County, San Luis Obispo County, Ventura County, and the southern portion of Kern County in which part of the Los Padres National Forest is located. Any fires intersecting these counties (or intersecting the Los Padres in Kern County) were included in the analysis. Fire data was collected from the Cal Fire FRAP database and population data was collected from the U.S. Census Bureau.

As more people pack into our region, the chance for wildfires to ignite increases, and they are occurring far more frequently than they did centuries ago. Over 56% of the Los Padres National Forest has burned just in the last 20 years and many of those areas have burned two or three times in the last 50 years. The Los Padres has one of the most negative fire interval return departure (FRID) values of any national forest in California, meaning that fires occurring in the same area are doing so with less time between them.

Fire is occurring too frequently for many of our native chaparral species to keep up. For example, species that only grow from seed following a fire are not given a chance to mature and produce more seed if another fire occurs in the area too soon. Eventually, areas that burn too frequently for too long will undergo “type conversion” — the permanent conversion of native chaparral to nonnative weeds and grasses. These nonnative plants do not stabilize the soil or provide food and shelter to wildlife nearly as well as chaparral species. And there’s evidence that grasslands and invasive weedlands burn more quickly when wildfires do ignite, putting people and homes in their path at greater risk.

An often-recited myth is that wildfire suppression over the last century has caused an unnatural amount of vegetation to build up, increasing the likelihood of large and intense fires. This logic does not apply to chaparral and the latest science suggests that modern fires in our region are not outside of historical norms for fire size. Chaparral is naturally characterized by dense, dry shrubs. These plants may often seem dead, but are actually uniquely adapted to tolerate drought and intense sunlight. Next time you are hiking through the chaparral, take some time to look closely at the shrubs around you. Most plants have dead limbs attached to healthy, live plant parts. In our region, the myth that vegetation is too dense or that it is “decadent” or dead because of past fire suppression efforts can have real consequences on the management of ecosystems that naturally experience intense but infrequent crown fires. When chaparral wildfires do ignite, we fully support efforts to suppress them as quickly as possible.

Protecting Communities and Ecosystems

The Whittier Fire of 2017 burning in the Los Padres National Forest above Goleta. Photo by Bryant Baker.

Many ideas on how to protect people and structures from wildfire in our region have developed over the last century. These often involve constructing fuel breaks, clearing “brush,” and conducting controlled burns to thin areas of vegetation that may burn during a future wildfire. Despite the good intentions, many of these techniques are not effective in preventing wildfires or slowing their growth, and they can have significant environmental consequences. In fact, these methods are often adapted from use in the hardwood and coniferous forests found far north and east of our region, and even in those regions their efficacy has been called into question by the latest science.

Real Solutions

How do we protect communities from wildfire? This question has a complex answer with many possible solutions. First and foremost, we need to redouble our efforts to reduce the number of wildfire ignitions. For example, the 2017 wildfire season showed that we need to start thinking about underground power lines in high-fire areas. We also need to ensure that our firefighters have all of the tools and emerging technologies they need to quickly detect wildfires as soon as they start, and to mobilize initial attack resources even more quickly than they already do.

In addition to the need for reducing wildfire ignitions, we have long advocated for smarter development practices:

- Avoiding building homes in fire-prone areas within the “wildland urban interface”

- Maintaining smart defensible space around structures

- Building or retrofitting homes using fire-safe materials.

Development in the wildland urban interface is a growing side effect of urban sprawl in local cities. Too often, developments are approved in areas with significant fire risk. This puts considerable pressure on land managers to prevent fires from moving into these areas and threaten lives and property. Communities throughout California have long understood the need to avoid building in floodplains, and the same logic needs to be applied to building in areas at high risk for wildfire. Limiting the construction of homes and other buildings in areas of high fire risk can greatly mitigate wildfire damage in the future. Reducing development in fire-prone areas may also decrease the probability of human-caused ignitions there.

For homes and structures that already exist in areas at risk of being affected by wildfire, defensible space is a first step to better-protecting your home. Fire scientists recommend clearing vegetation no further than 100 feet from your buildings. Reducing woody vegetation immediately adjacent to structures by about 40% while also ensuring that other vegetation does not overhang or touch structures have been shown to be some of the best measures a homeowner in fire-prone areas can take.

During high-wind conditions, embers (also called “firebrands”) can be spread up to a mile or more, creating a dangerous situation where houses far away from the flames can ignite. Retrofitting existing homes or building new homes and structures with fire-safe materials can significantly reduce the risk of fire damage from firebrands. These steps include replacing roofing — one of the most vulnerable parts of your home — with non-wood materials such as fiberglass-asphalt shingles, metal sheets, clay tiles, or slate. Vents should also be covered with screens to inhibit ember entry into your home and they should be cleared of any vegetative debris on a regular basis. Other techniques include installing double-paned windows to reduce the heating of indoor materials from a fire outside and sealing all wall junctions and other potential points of entry for smoke and embers.

Going forward, our communities should rethink how — and whether — new development should be approved in the wildland urban interface. Homeowners already in fire-prone areas can take control of their home’s safety by replacing flammable wood shingles, installing double-pane windows, and installing innovative equipment designed to protect homes from fire such as rooftop sprinklers. All of these approaches have been shown to work time and again and they place the responsibility of protecting our communities on us collectively rather than placing the blame of wildfire destruction on our unique ecosystems.

The Wrong Approach

Many of the ideas for how to protect communities involve vegetation removal in remote areas and large-scale landscape alterations. This approach may involve activities such as prescribed fire, vegetation thinning, and fuel breaks — techniques that are often ineffective in areas dominated by chaparral and will not alter regional wildfire trends.

Prescribed fire only exacerbates the type conversion process and doesn’t necessarily reduce an area’s risk of burning later, with studies concluding that it is not a cost-effective method in chaparral. This can be easily seen by overlapping wildfire burn areas in and around the Los Padres National Forest. For example, the 2017 Thomas Fire burned most of the areas burned by 1985’s Wheeler and Ferndale Fires, areas burned by the 2003 Piru Fire and 2006 Day Fire, and canyons that burned in the 2008 Tea Fire and 2009 Jesusita Fire. The 2016 Soberanes Fire burned over half of the area burned by the 2008 Basin Complex Fire in the Monterey Ranger District. Prescribed burns in chaparral would probably have to be conducted very frequently (every five years or less) in order to be effective, and as described above, overly-frequent fire in chaparral can have serious environmental consequences.

The timing of prescribed burns is also of concern to fire scientists. Prescribed burns must be conducted during a narrow window in order to be successful due to vegetation moisture levels and weather conditions, meaning they are often done in winter or spring when many wildlife species are breeding and birds are nesting in the area. Prescribed burns during this time may heat up the moist soil to the point that seeds are damaged by the resulting steam. And there is always the risk of prescribed burns escaping and becoming full-fledged wildfires. Likewise, clearing or thinning vegetation in the backcountry would do little to stop the spread of wildfires.

There is evidence that Native Americans used prescribed fire along the central coast before Europeans settled in our region. However, scientists have determined that prescribed fire was being used to purposefully convert the dense chaparral to grasslands to allow for movement across the landscape, the creation of open hunting areas, the selection of edible herbaceous plants, and the reduction of habitat for potentially dangerous predators such as grizzlies — not to reduce the incidence of large wildfires. Many of the areas that were converted from chaparral to grassland were then maintained by European settlers once they arrived.

You can read more about the issues with prescribed fire in chaparral ecosystems here.

The massive Camino Cielo Fuel Break — seen here in 2008 — is frequently cleared of native vegetation.

Fuel breaks are another method commonly employed in the Los Padres and throughout nearby public and private lands. A study in 2011 showed that in the Southern California national forests — including the Los Padres — fuel breaks often do not stop wildfires, especially when weather conditions such as strong winds are present. The 2017 Thomas Fire and other large, wind-driven wildfires in our region easily jumped fuel breaks, highways, and other land features due to embers being blown far in front of the fire’s leading edge. These wildfires tend to be the largest and most destructive, and unfortunately fuel breaks are often ineffective in slowing their movement. For example, the Thomas Fire completely jumped a network of 70 miles of fuel breaks in the national forest around Ojai and Lake Casitas, and the fire was moving too quickly for firefighters to safely access these areas.

Remote fuel breaks threaten rare and sensitive species such as the Refugio manzanita. Photo courtesy California Chaparral Institute.

Despite the science, remote fuel break projects are still approved throughout our national forest. These fuel breaks are often built far away from communities at risk, and they involve initially clearing most mature vegetation and favoring regrowth of nonnative grasses and weeds. A common method of establishing fuel breaks involves mastication, or the crushing of vegetation down to bare soil. This method has been shown to reduce bird numbers by 60% and can have significant implications for biodiversity. Fuel breaks can be as wide as a football field and several miles long, removing prime habitat for many plant species that are only found in small populations along ridges in our region such as the Refugio manzanita. These plant species provide food and shelter to native birds and insects that are critical for ecosystem health. The size and length of fuel breaks and their composition of nonnative plants unfortunately makes them likely conduits for invasive plant movement into new areas, further impacting native plant and wildlife habitat.

Recommended Reading

We base all of our positions on the most current and best available science. Many of the studies whose results and recommendations contributed to our understanding of fire ecology in and around the Los Padres National Forest are cited above. Check out our Fire References page for a full list of scientific journal articles, books, and other materials we recommend reading for more information on these complex and important topics.